Human mortality is a universal fact. However, the beliefs of the afterlife, or what lies beyond death are often culturally specific. These beliefs originate from the realm of the unknown. And what is unknown is often feared. According to philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, it is ‘the fear of death that is the beginning of philosophy, and the final cause of religion’ (Durant, 1977, p. 328). The focus of a sociological study of dying, death, and bereavement is, however, slightly different – a point that one seeks to make in this short essay.

One recognizes that societies have developed different methods, rituals, activities, etc. to manage death or the act of dying. At the societal level, the events surrounding deaths can run unruffled but at an individual level, they still arouse feelings of discomfort. A sociological perspective of death, however, would ask whether this discomfort is true of all societies throughout history, or is it something specific to late modernity?

Sociology of death emphasises the context-specific nature of death. Sociologists like Anthony Giddens has argued that in high modernity, there is the sequestration of death (Giddens 1991). It is routinely hidden from view – something that happens in ICUs. But the COVID-19 pandemic has changed this. While the virus arrived with affluent international travellers, it soon engulfed all parts of the country. The stories of COVID-19 show this. The tragic story of how migrants have died as they sought to reach home tells us how the pandemic affects different sections of the population differently even in death.[i] Death has become a public event.

ーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーー

Read similar posts on our blog

While many COVID-19 deaths would still take place within the hospital buildings, sequestration of death is hard to maintain. Every day the state declares the numbers of the dead while in a world of instant communication through mass media death is now ‘beamed’ to our homes ‘live’. Death, in a way, does not belong to the person anymore.

The question could be asked whether it ever was. Capital punishments, terrorism, communalism, mob lynching all revolve around the politics of death. And herein, the state has a defining role to play just as it does in the glorification of a deceased soldier’s death. As the pandemic rages on, the state in many parts has told us that we must learn to live with it; even if some of us will die. A certain routinisation is underway.

Ideas of death are also tightly knit to people’s imagination and memory. Death facilitates collective remembering, reaffirming continuity between a society’s past, present, and future. Sandra Bertman writes:

The dead do not leave us: they are too powerful, too influential, and too meaningful to depart. They give us direction by institutionalising our history and culture; they clarify our relation to country and cause. They immortalise our sentiments and visions in poetry, music, and art. The dead come to inform us of tasks yet to be completed, of struggles to be continued, of purposes to be enjoined, of lessons they have learned (Bertman 1979:151).

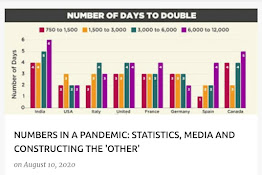

This collective memory, however, differs across cultural spaces. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, one can argue that memories are to some extent transcending cultural barriers. The regular media announcement of the demise of COVID-19 patients, as well as the disease in itself, creates a sense of familiarity with the disease which was unknown to us just months ago. This awareness does cut across societies. However, what is starkly visible too are the class, caste, region differentiated nature of deaths during this pandemic.

Finally, even as we know that death is an intense and emotionally charged phenomenon, it is essential to recognise that emotions too are sociological. Social processes and structures impinge on the way it is conceptualised, experienced, and responded to (Thomson et al. 2016).

References:

Bertman, Sandra. (1967). ‘Communicating with the Dead: An Ongoing Experience as Expressed in Art, Literature and Song’ in Robert Kastenbaum, ed., Between Life and Death. New York: Springer.

Durant, W. (1977). The story of philosophy. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Giddens, Anthony. (1991). Modernity and Self-identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Stanford University Press.

Thomson et al. (2017). Handbook of Sociology of Death, Grief, and Bereavement: A Guide to Theory and Practice. Taylor and Francis.

[i] Hindustan Times has reported that around 80 people have died on board the Shramik Special trains in the period between 9th to 27th May 2020. In a gruesome incident, a 45-year-old migrant labourer was found dead in a toilet of a Shramik Special train when it was being cleaned by workers at Uttar Pradesh’s Jhansi station, four days after he boarded it for Gorakhpur, officials said on Friday. The body was found when the train was opened for maintenance and sanitisation on 27th May and he had boarded it on 23rd May. The viral video of a toddler trying to rouse his dead mother at Muzzafarpur Railway Station in Bihar also had a Shramik Special train connection. The woman had boarded a train from Ahmedabad. https://www.theweek.in/news/india/2020/05/30/80-people-have-died-on-shramik-trains-for-migrants-report.html, accessed on 25th June 2020.

Anushila Baruah has an MPhil from the Zakir Hussain Centre for Education Studies (ZHCES), Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). She has also worked as a guest faculty in the Department of Sociology, Gauhati University and the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Guwahati.