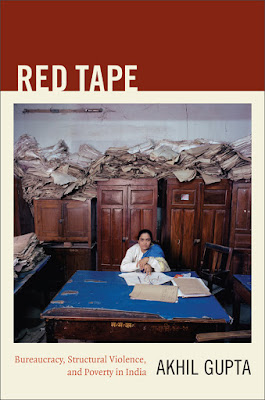

Akhil Gupta’s engaging book begins with the puzzle of – a high number of deaths due to poverty in India not being viewed as a crisis despite the inclusion of the poor in national sovereignty and democratic politics. Gupta is intrigued by the invisibility of such violence in the public domain. Why are these deaths not viewed as a crisis? What makes this violence invisible? What is the reason behind this seeming apathy despite the state deriving legitimacy from bettering lives of the poor? To answer these questions, Red Tape builds on Gupta’s earlier work dealing with themes of development, agrarian transformation, state practice, globalization, and environmental history. Gupta’s penchant for approaching these “economic” issues through an anthropological lens offer not only new theories for thinking about them but also juxtapose questions of postcolonial development with politics and governance.

Gupta’s compelling theory of “structural violence” borrows from Galtung’s and Paul Farmer’s work. Gupta argues that violence against the poor is enacted through the everyday practices of bureaucracies (p. 33). Bureaucratic action systematically produces arbitrary outcomes in its provision of care, actively condemning the poor to death through state policy, deaths which were preventable (p. 6). Gupta’s detailed theoretical framework to support his argument makes the book engaging. The painstaking development of the concept of “structural violence”, of why these deaths are more than just thanatopolitics (letting die), the move away from the reified state to understand the production of arbitrariness make the theoretical sections of this book compelling. Rather than being another book utilizing Foucault and Agamben’s concepts, Gupta builds upon their framework in intelligent ways.

To look at the everyday practices of bureaucracy, Gupta rejects Foucault’s and Agamben’s reified state in which the disciplinary power is inherently rational and organized. The first two chapters of the book build on Western theories of bare life, biopolitics and governmentality and interrogate their relevance to a postcolonial context. In doing so, there is a refreshing shift away from viewing developing countries in general, and India in particular, at an earlier stage of development, with Western developed nations as their telos of development and modernity. While he uses Foucault to argue the normalization of high deaths due to poverty as a statistical fact, he also underscores the undertheorized nature of violence implicit in biopower. Biopower understood through a managerial focus does not explain why some people get killed, and others don’t (p. 16). With examples from his, fieldwork Gupta shows the inefficiencies of Census data collection, questioning the statistical underpinning of the biopolitical project. Additionally, he argues that the poor are homo sacer, where they can be killed without sacrifice, without a state of exception (unlike Agamben’s argument).

The rigorous theoretical intervention is supported through an ethnographically thick argument that connects bureaucratic actions to the arbitrariness of outcomes. To investigate how ethics and politics of care are arbitrary and this arbitrariness is systematically produced, Gupta considers three themes of interaction between bureaucracy and the poor: corruption (chapters 3 and 4), inscription (chapters 5 and 6) and governmentality (chapter 7). The rich ethnographic vignettes of corruption are replete with Gupta’s subtle interpretations in conversation with people which add depth to his ethnographic work. For example, his astute interpretation of the body language, spatial arrangement and tone of conversation in the action of two patwaris (p. 84 -85) is evidence of ethnographic work of high calibre. His investigation of the role of narrative in the cultural construction of the state and the normalization of corruption focuses on looking at newspapers and comparison of the representation of the state in a popular novel and a well-known ethnography of India. By astutely utilizing quasi-ethnographic sources like popular novels, Gupta provides a diverse ethnographic understanding of how poor people’s understanding of the state is shaped by representations of corruption and circulation of discourses about corruption.

The investigation of the political consequence of bureaucratic insistence on writing in a context of widespread illiteracy is a fascinating way of looking at structural violence and production of arbitrariness. Moving away from the assumption that writing is functional, Gupta argues that the state is constituted through bureaucratic writing. The poor show agency in dealing with this situation by counterfeiting documents, educating their children and through political connections. His argument would have been bolstered if he would have grappled with Chatterjee’s (2004) “political society” in some depth. Chatterjee’s thesis on the community-based modality of claims making by political society seemed to be an explanation for the phenomena being observed (how the poor were engaging with political mobilization to get around bureaucratic hurdles, the Bharatiya Kisan Union being a case in point).

The investigation of the political consequence of bureaucratic insistence on writing in a context of widespread illiteracy is a fascinating way of looking at structural violence and production of arbitrariness. Moving away from the assumption that writing is functional, Gupta argues that the state is constituted through bureaucratic writing. The poor show agency in dealing with this situation by counterfeiting documents, educating their children, and making political connections. His argument would have been bolstered if he would have grappled with Chatterjee’s (2004) “political society” in some depth. Chatterjee’s thesis on the community-based modality of claims making by political society seemed to be an explanation for the phenomena being observed (the manner in which the poor were engaging with political mobilization to get around bureaucratic hurdles, the Bharatiya Kisan Union being a case in point).

These minor points notwithstanding, Gupta’s engaging local level ethnography into everyday bureaucratic procedures of a disaggregated state perpetrating violence is particularly pertinent during the pandemic. The Indian state’s approach to the pandemic was a draconian nation-wide lockdown announced with four hours’ notice. What unfolded was a spectacle of misery, with migrant workers left to fend for themselves. Gupta’s analysis of unintended outcomes by showing how they are systematically produced by the friction between agendas, bureaus, levels, and spaces that make up the state (p. 47) helps make sense of what has been called the “migrant crisis” and the Indian government’s handling of the pandemic by controlling narratives, normalizing infections and deaths through statistics, and its healthcare and policing hamstrung by their daily processes.

Bibliography

Chatterjee, Partha. The Politics of the Governed: Reflections on Popular Politics in Most of the World. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004.

Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci (Volumes 1, 2 & 3). Trans. Hoare, Quinton and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. New York: International Publishers, 2005 (1971).

Scott, James. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

***

Parnika Praleya is currently a graduate student at the University of Chicago. Her research interests lie in institutions and contentious politics and her research focuses on structural determinants of media polarization in parliamentary democracies and looking at the impact of war-time social movements in civil war-affected regions. When not researching, she can be found reading Wodehouse, dabbling in photography, and traveling. Her blog, Maverick Feet (https://maverickfeet.wordpress.com ), is a reflection of all that she is.