Introduction

The world we live in and know of is suffused with signs. As we walk down roads, huge billboards loom over us. At home, television sets beam advertisements; our phones are inundated with messages. There are signs everywhere. The car we drive or aspire to buy; the sunglasses one wears; the modular kitchens that we fantasise about are also signs – in the sense that they bear meaning and impart prestige and standing to the individual in the realm of sign value.

Scholars confronted with the proliferation of sign value in affluent consumer western societies sought to theorise this phenomenon. For instance, Baudrillard combined semiological studies, Marxian political economy, and sociology of the consumer society to explore the system of objects and signs which forms our everyday life. Advertising, packaging, display, fashion, sexuality, mass media and culture, and the proliferation of commodities multiplied the quantity of signs and spectacles. There was a surfeit. Baudrillard claims that commodities are not merely characterised by use-value and exchange value, as in Marx’s theory of the commodity. Sign-value — the expression and mark of style, prestige, luxury, power, and so on — becomes an increasingly important part of the commodity and consumption (see Goldman and Papson 1996).

This essay seeks to explore the meaning of a sign and that of sign value, focussing on the long history of theorising sign, albeit in a condensed fashion. Every phenomenon around us signifies something. We have signs of nature, culture, affluence and poverty. We may not ‘experience’ nature in the realm of the physical world, but we can travel to a ‘place’ virtually to ‘experience’ virtually and consume ‘pristine nature’. It further seeks to argue on the lines of Baudrillard that in the contemporary world where signs dominate, the referent may get disconnected, and we would be left with signs alone.

Signs and Theory of Signs

Signs may appear in verbal, literate or written, and in visual forms as well. The whole objective world, i.e. the world full of objects, is therefore known by its signs that may evoke deep subjective meanings. Ideas used to generate this may be denotative and connotative. Connotation and denotation are not two separate things/signs. − Connotation represents the various social overtones, cultural implications, or emotional meanings associated with a sign. Denotation represents the explicit or referential meaning of a sign. Denotation refers to the literal meaning of a word, the ‘dictionary definition.’ For example, the name ‘Bollywood’ connotes such things as glitz, glamour, tinsel, celebrity, and dreams of stardom. Simultaneously, the name ‘Bollywood’ denotes an area of erstwhile Bombay, now named Mumbai, known as the centre of the Indian movie industry. Take the instance of the conversation below from the film ‘Hindi Medium”, and one will witness the social overtones and cultural implications of words.

- Keya…Naam keya hain aap ka?

- Hamara? Aare Bhai! Naam to bade kaamwalo ke hote hain; Hamara kaun sa naam?

- Dhaabe pe lag jaye to ‘Chhotu’; Pet nikal gaya ‘Motu’, Pat badh gaya ‘Lambu’; Saman utha liya to ‘Coolie’; Ped lagaya to ‘Maali’; Nahin to ‘Maa-Bahen ki Gaali’; Baki jiske man me jo aata hain bak deta hain;

- Bhai, Maa-Baap ne bhi to rakkha hoga koyi naam?

- Haan…maa-baap ne naam dhhara ‘Somprakas’; par kisi ne bulaya nahin aj tak.

Sign theories have a long history. Let us touch upon just a few. In one of his many definitions of a sign, Peirce writes:

I define a sign as anything that is so determined by something else, called its Object, and so determines an effect upon a person, which effect I call its interpretant. The latter is thereby mediately determined by the former.[i]

What we see here is Peirce’s basic claim that signs consist of three inter-related parts: a sign, an object, and an interpretant.

The relationship is not simple. It is not a matter of languages as a way of denoting things and actions. Saussure argued that it is not things, but our conception of things, actions, and ideas, that are part of our language, not names, but schemas in the brain capable of being evoked by certain combinations of sounds. In one of his last lectures, he introduced the terms significant ‘signifier’ for the acoustic image and signifié ‘signified’ for the concept. The story gets compounded further in today’s hyper-real world pervaded by signs.

Signs in a sign suffused world

I begin with a quote from Baudrillard:

The simulacrum is never that which conceals the truth – it is the truth which conceals that there is none.

The simulacrum is true. [ii]

There is the reference to Borges tale “where the cartographers of the Empire draw up a map so detailed that it ends up exactly covering the territory”. But with the decline of the Empire, this map becomes frayed and finally ruined, a few shreds still discernible…bearing witness to an imperial pride and rotting like a carcass”. This fable would then have come full circle for us and now has nothing but the discrete charm of second-order simulacra.

Abstraction today is no longer that of the map, the double, the mirror or the concept. Simulation is no longer that of a territory, a referential being or a substance. It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal. The territory no longer precedes the map nor survives it. Henceforth, the map that precedes the territory – precession of simulacra – is the map that engenders the territory. If we were to revive the fable today, it would be the territory whose shreds are slowly rotting across the map. It is the real, and not the map, whose vestiges subsist here and there, in the deserts which are no longer those of the Empire, but our own. The desert of the real itself. [iii]

To dissimulate is to feign not to have what one has. To simulate is to feign to have what one hasn’t. One implies a presence, the other an absence. But the matter is more complicated since to simulate is not simply to feign: “Someone who feigns an illness can simply go to bed and pretend he is ill. Someone who simulates an illness produces in himself some of the symptoms” (Littre). Thus, feigning or dissimulating leaves the reality principle intact: the difference is always clear, it is only masked, whereas simulation threatens the difference between “true” and “false”, between “real” and “imaginary”. Since the simulator produces “true” symptoms, the question that can be raised is he or she ill or not?

I had mentioned earlier that Baudrillard combined semiological studies, Marxian political economy, and sociology of the consumer society to explore the system of objects and signs which forms our everyday life. Some have argued that for Lukàcs, the Frankfurt School, and Baudrillard, reification — the process whereby human beings become dominated by things and become more thing like themselves — comes to govern social life. Conditions of labour imposed submission and standardisation on human life and exploiting workers and alienating them from a life of freedom and self-determination. In a media and consumer society, culture and consumption also became homogenised, depriving individuals of the possibility of cultivating individuality and self-determination.

In a sense, Baudrillard’s work can be read as an account of a further stage of reification and social domination than that described by the Frankfurt School who described how individuals were controlled by ruling institutions and modes of thought. Baudrillard goes beyond the Frankfurt School by applying the semiological theory of the sign to describe how commodities, media, and technologies provide a universe of illusion and fantasy in which individuals become overpowered by consumer values, media ideologies and role models, and seductive technologies like computers which provide worlds of cyberspace. Eventually, he will take his analysis of domination by signs and the system of objects to even more pessimistic conclusions where he concludes that the thematic of the “end of the individual” sketched by the Frankfurt School has reached its fruition in the total defeat of human subjectivity by the object world. [iv]

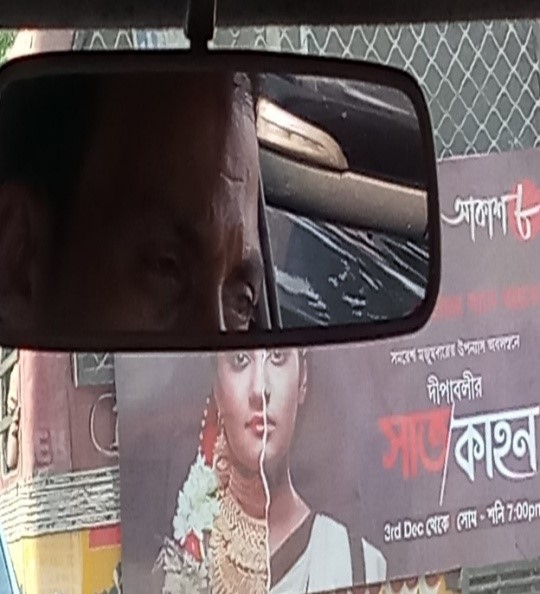

A study of two photos and that matter of sign

A photograph itself is a coded sign that may transcend fixed meaning (Barthes, 1964). French poststructuralist Jacques Derrida defines it as ‘transcendental signified’ where meanings transcend their original or primary logocentric meanings. Let’s analyse two such photos snapped recently.

———————————————————————————–

———————————————————————————–

Following the constellation of theoretical arguments, these two photographs can be defined respectively as the ‘sign of labour’ and ‘sign of a model from a taxi windscreen’. But it can be interpreted in other ways. Both photographs bear a unique code within which the signs are placed in an order. These are ‘order of signs’ instead of the ‘order of objects’. Here involved, is the signifier of the photographer who deliberately has taken it and made it significant in this particular context. The ‘model-sign’ of the first photo and the ‘driver-sign’ of the second photo can therefore be included in the analysis. This raises a further question whether these two signs will neutralise one another or be juxtaposed anyway or will dominate one another.

Abir Chattopadhyay is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Mass Communication and Journalism, S.A. Jaipuria College, University of Calcutta.

References:

- Barthes, Roland: Image Music Text; Translated by Stephen Heath; Macmillan Publishers; New York 1978.

- Chattopadhyay, Abir: Communication Media Cultural Studies: Beyond Development; Progressive Publishers, 2010, Kolkata, India.

- Goldman Robert and Stephen Papson 1998 Nike Culture: The Sign of the Swoosh, Sage Publications: London

- Fiske, John: Introduction to Communication Studies; Routledge; 2003.

[i] https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/peirce-semiotics/, accessed on 12th April 2020.

[ii]https://web.stanford.edu/class/history34q/readings/Baudrillard/Baudrillard_Simulacra.html, accessed on 12th April 2020.

[iii]https://web.stanford.edu/class/history34q/readings/Baudrillard/Baudrillard_Simulacra.html, accessed on 12th April 2020.

[iv] https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/baudrillard/#Bib, accessed on 12th April 2020.