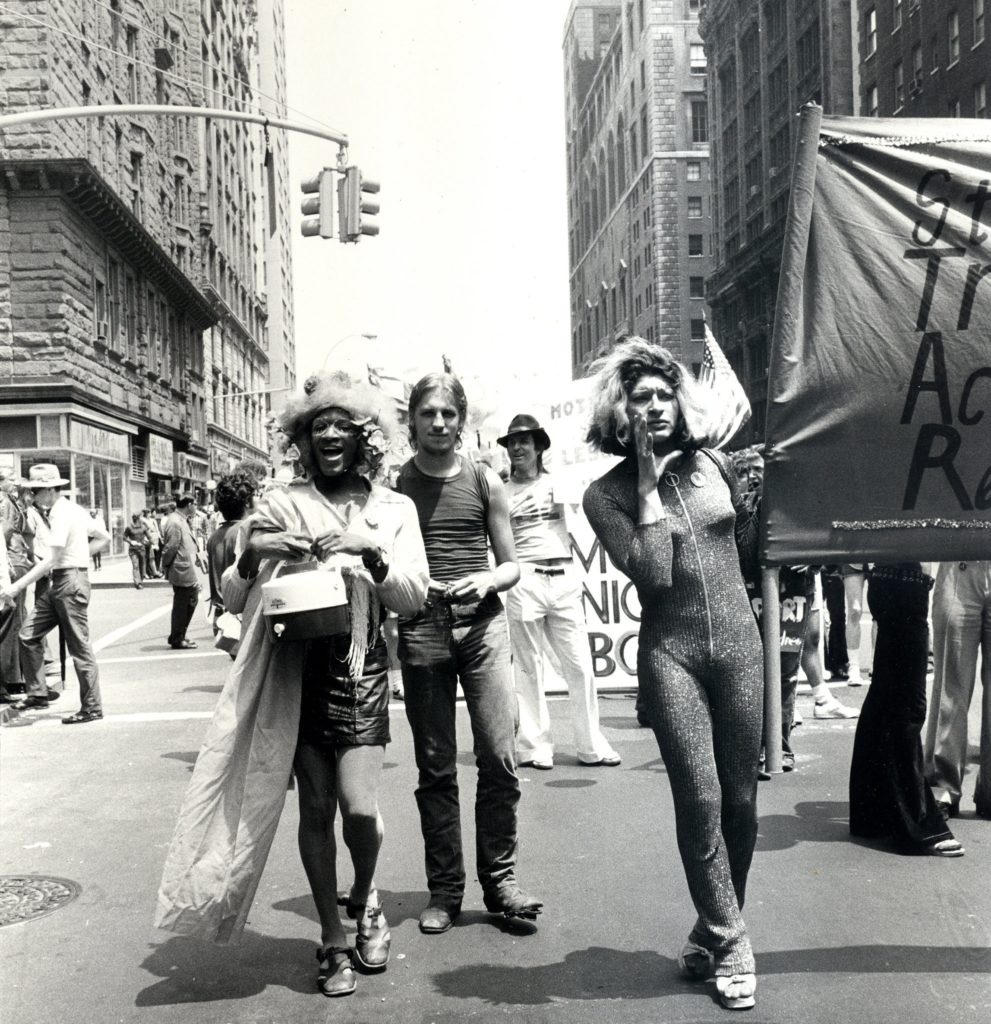

Since June is the Pride month and July the Disability Pride month, I wanted to look for the presence of disability within Pride and vice versa, especially in India. Black transgender activist Marsha P. Johnson hailed for leading the Stonewall riots, was also a person with disabilities. Not only was she responsible for the very first Pride in 1969, but she also fought racism, the prison system, transphobia and the medical system. She started Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) with Puerto Rican transgender activist Sylvia Rivera. STAR worked toward justice for young transgender people, many of whom were women of colour with a disability. Johnson demanded free access for people with disabilities and doctors to stop treating them for their gender identity and sexuality.

With such an icon- a transgender activist with a disability having taken the original charge, it is unfortunate that there is little to no visibility of disability among the varied sexualities or even people with disabilities having come out as queer (used hereon to stand for the LGBTQIA+ acronym). Shakespeare et al. (1996) list out names of some famous personalities with disabilities who were known to be queer- Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Montgomery Clift, Frida Kahlo, etc. There are hardly any Indian icons in the same category who have shot to fame.

It must be kept in mind that Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) that decriminalised homosexuality in India was scrapped only in September 2018. However, that does not mean that conversations around sexuality or even sexuality within disability have not existed. Kiran, a trans man with a disability belonging to an Adivasi community, had to run away with his partner as they faced opposition from their families. With a little positive coverage in the media, they were helped by a crisis centre right when they were planning to die by suicide. Since then, Kiran and his partner have been working as disability, and trans rights activists with his own community-based organisation in Karnataka named NISARGA.

Kiran’s is one of the very few journeys that came to light. Many others continue to remain veiled. And it seems imperative to dig deeper into why one still fails to find a discussion of the prevalence of sexualities within disabilities. This even when post-humanist critical disability studies challenges humanism’s colonisation of the body and psyche via medicalisation and psychologization. It dismantles normativity. And yet, it somehow continues to remain largely heterosexist and within the binaries of gender, with queerness finding little mention in this space.

Shakespeare et al. (1996) elaborate on the various obstacles that lie in the way of this visibilisation. The biggest reason is the desexualisation and infantilisation that people with disabilities are subjected to. Conversations around sex and sexuality are especially discouraged because they are seen as people who are dependent on someone for care, like children. This becomes even more aggravated as children with disabilities are put in separate schools. With negative messages about sexuality and separation, institutionalisation works toward creating massive segregation and the notion of difference. In this way, these children are not only kept away from interaction with other children their age but also denied the development of self-esteem and self-actualisation.

We need to keep in mind what Shakespeare et al. (1996) write about in the British context. Sex and sexualities are anyway stigmatised topics of discussion in Indian society. The acceptance and expression of various identities would only be possible if sexuality concerns are addressed accurately, are accessible and are age-appropriate. This remains a challenge with little to no investment of time, material, educational and trained human resources in this regard (TARSHI, 2018).

TARSHI’s report mentions that the original text of the draft National Education Policy (NEP) 2016 mentioned the word ‘sexual’, which was removed altogether. Sex education was renamed ‘The Adolescent Education Programme’ and ‘National Population Education Programme’ in the draft. Finally adopted in 2020, the NEP failed to bring into its ambit anything that could be remotely related to sex education, not even the terms mentioned in its drafts.

And when these needs are attended to, the dialogue only revolves around sexual health and protection from abuse- mostly from the lens of violence. A 2018 article in The Print talks about the rolling out of the ‘school health education programme’ by the Prime Minister, which would teach students about good touch and bad touch through role-play and activity-based programmes (The Print 2018). It will not be easy to have the intersection of disability and sexuality in an institutionally ratified curriculum.

While pointing this gap, TARSHI’s report fails to bring in queer disabled voices. In a report 228-page on sexuality and disability, the study barely mentions the terms ‘lesbian’ (5 times), ‘gay’ (9) and ‘bisexual’ (4). Most of the time, these words are mentioned independently, without any connection g drawn to ‘disability’. The word ‘transgender’, though, finds 31 mentions. One of the reasons for this can be that alternate sexualities are themselves seen as disabilities. TARSHI’s study points to a 2016 survey by Buzzfeed News that reports that 69% of Indians believe that transgender people have a form of physical disability, and 59% think of it to be a kind of mental illness. This even when they think that the rights of transgender people must be protected.

Shakespeare et al. (1996) point out that such everyday environmental, attitudinal, and institutional barriers lead to discrimination and exclusion. Susan Bordo (1993) talks about the concept of “direct grip”. She suggests that the bodily lessons we learn through routine and habitual activity are far more effective politically than explicit instructions on appropriate behaviour. This disciplining and normalisation of the body is an amazingly durable and flexible strategy of social control and helps in the creation of docile bodies. Since bodies with disabilities experience being the lesser embodiment- the ‘other’, they internalise this oppression and are socialised into the heteronormative patriarchal system that denies them the expression of sexuality.

It is important to point out that while heterosexism mars the disability world, the homosexual world is also coloured with ableism. Shakespeare et al. show how various respondents talk about gay/ lesbian bars in basements where stairs are the only way to access them, notwithstanding the inaccessible toilet facilities. While such places of expression stay underground in India, the Pride parades act as the perfect sites to gauge the visibility of disability which remains close to nil.

Films like Sixth Happiness (1997), Margarita with a Straw (2014), AccSex (2020) draw attention to the various sensual desires and sexualities of people with disabilities in the Indian context. However, these bold steps are marred when scholars say that these depictions speak for the “elite few” and that sexuality must be understood as “not just a physical need for sex but a desire for companionship, emotional connection and mutual respect between partners” (The Tribune, 2015).

Since we are not too far away from the starting line in India with homosexuality getting decriminalised only three years back, maybe we can take a step back and reset our expectations. Unlearning our ableist, heterosexist notions will help visibilise and embrace differences which would lead to better and more informed discourses on the intersections of disability and sexuality.

References:

- Bordo, S. (1993) Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture and the Body. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bose, S. (2015). Margarita with a Straw. India: Viacom18 Motion Pictures.

- Ellison, J. (undated). Teachable Trans History: Marsha P. Johnson. WordPress: Blog. (Link: https://jmellison.net/if-we-knew-trans-history/teachable-trans-history-marsha-p-johnson/, accessed on 7th June 2021)

- Ghosh, N. (2010). Embodied Experiences: Being Female and Disabled. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 45 (17), 58-63.

- Goodley, D. Lawthom, R. Cole, Katherine (2020). Posthuman Disability Studies. Subjectivity, Vol. 7, 342-361.

- Hussein, W. (1998). Sixth Happiness. UK: 20th Century Fox.

- Nagaraja, P. Aleya, S. (2018). Sexuality and Disability in the Indian Context. India: TARSHI

- Oliver, D. Ali, R. (2019). Why we owe Pride to black transgender women who threw bricks at cops. USA: USA Today (Link: https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/voices/2019/06/24/pride-month-black-transgender-women-stonewall-marsha-p-johnson/1478200001/, accessed on 7th June 2021)

- Pandit, N. (undated). The Story of Kiran, a disability and trans rights activist. India: Sexuality and Disability (Link: https://sexualityanddisability.in/always-remember-that-you-have-reasons-to-smile-kiran-a-disabled-trans-activist/, accessed on 7th June 2021)

- PSBT. (2020). Accsex. India: Youtube. (Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xm4arz1JCKo, accessed on 7th June 2021)

- Shakespeare, T. Gillespie-Sells, K. Davies, D. (1996). The Sexual Politics of Disability: Untold Desires. London: Cassell.

- Sharma, K. (2018). Coming soon in Indian classrooms: Sex Education 2.0. India: ThePrint (Link: https://theprint.in/india/governance/coming-soon-in-indian-classrooms-sex-education-2-0/49614/, accessed on 7th June 2021)

- Vaidya, S. (2015). Sex and Sexuality. India: The Tribune. (Link: https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/archive/features/sex-and-sexuality-80439, accessed on 6th June 2021)

***

Prerna (she/they) is a PhD candidate at Ahmedabad University. A postgraduate in Gender Studies, her research interests include gender, sexuality, work and leisure. Currently, she is working as a fellow in Equity and Gender in Education with Transform Schools.