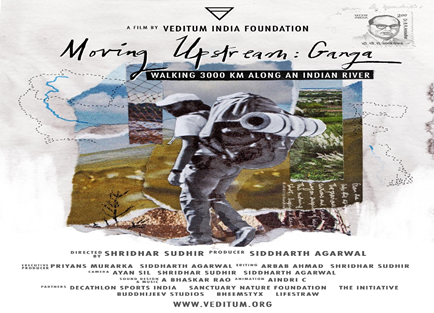

Facing downwards, sideways, or sometimes hazed, the camera forms an angular relationship with the river, as Siddharth wrestles as he walks on the uneven edge of the river’s bank built by a long history of deposited sediments – folded in time of a river so different from what we know now. The documentary begins as a collective effort of a few friends –from streams to a river, merging and departing as the plot thickens and stories evolve. The duo-protagonist, Ganga (the river) and Siddharth remain united in spirit on this journey. Beginning from downstream in Calcutta, Siddharth walks barefoot through uneven, patchy, but storied lives of Ganga River and the riparian communities alongside the banks. The journey covers 1600 kilometres – using ‘walking as a tool that has the capacity to disarm people’ says Siddharth.

In this passage, the storyline for the documentary encapsulates narratives as forms of telling – one in which both the narrator and the river dissolves the modern construct of water as a singular entity. Narratives of riparian communities illuminate an inner life of human stories fraught with struggles as flood plains shift, forming chaurs and diaras (deposition caused by the river). The documentary captures how these fluvial landscapes across Bengal and Bihar often emerge and disappear, not only as depositions but as an arsenal of collective memory containing lived lives of those who look at it from far away. The gripping stories of lost homes, livelihoods and now new forms of waterways transportation lay bare the difficulties of riparian people. In what seems like a very fraught storyline, I divide the documentary into two conditions of broad visual narratives.

Fishing net and extinction imaginaries

The fishing net in the documentary emerges as a metaphor for riverine control as Siddharth travels upstream in Uttar Pradesh. The colour of the river changes– more polluted, an emergent crisis of disappearing species. Suspended in dusk was a torchlight gleaming onto the face of two young fishermen on the boat, expressing their fear for fishing in certain areas and changing contours of their livelihood. While it functions as a sub-text to the narration, the extinction imaginaries emerging from stories of fishermen about the disappearance of a variety of fish. The impact of anthropogenic activities is tangible. In documenting this, Siddharth refuses to cast away the many voices textured with everyday, mundane experiences that are often lost in the official plot. Bouts of anger, jokes and tragedy – all of it comes as deeply personal stories of these riparian communities that create a seamless flow into the inner lives of the river.

These stories – of humans and non-humans (sometimes, river; while at the other the fish) repletes the sequences of visual display of landscapes, one that is, as Nadia writes, “is generative of entanglements with the river other than the usual ones of relying upon it for sustenance and transportation”.[i] The emphasis on localised, micro-interaction of communities with rivers allows viewers to transcend the limits of visual boundaries of a documentary and find themselves amidst the landscape of characters. In doing so, the foreground, the narrator (Sid and communities), becomes the background, and the background river becomes the foreground. The interplay of textured slippages between memory and tales as presented by communities forms an assemblage of a river’s imagination. These textured stories are presented by refusing to enforce a low-land basin riparian worldview with upstream cartography.

Fragile ecologies and fractured dreams

As the documentary progresses, the difference in the lifeworld of riparian communities and rising water infrastructure (Dams) complicates the narration. What was seen as extinction imaginaries, shifting fluvial landscapes (chaurs), takes forms of enormous infrastructural violence that manifest in the dam. While for decades, the documentation of dam stories has mainstreamed pressing concerns, the documentary captures the impact on their lives and their worldview. Spread across the road was a herd of sheep looked over by three elderly women – who sat down and recounted the stories of villages uprooted for dams, leaving away the traces of memory, joy, and harvest songs and belonging. These women point out almost helplessly towards the mountains – showing disappeared archives of their social world. In this passage of telling tales of lived lives, the storyline pierces into the heart of the viewer – mounting anger and transient pain is felt through their voices.

Riveting accounts of displacement are not merely physical, emotional, spiritual, and memorial. These voices gain strength as Siddharth moves upwards – documenting details of rupture and havoc on the fragile ecology of the Himalayas (Uttarakhand). Dams begin to appear as the burgeoning desire of Indian modernity – symbolising the hydropower of shining India story. This dream of hydro generation capacity drowns the ordinary lives of those who do not find their voice or are structurally erased. The documentary presents unheard narratives in visualising alternative symbols of those who pay the price against those Indians who are soaked in lives consumed by electricity. The battle is created. People are chosen. Lives are discarded. The documentary makes this evident.

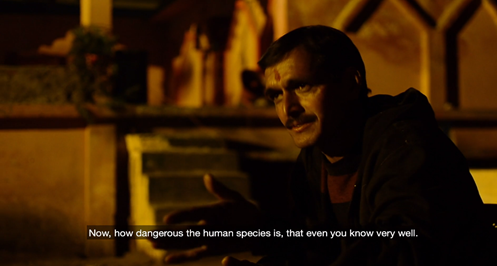

Lastly, perhaps intentionally or not, the documentary makes a scathing political commentary of what we call Anthropocene – a geological epoch in which human activity has been the dominant influence on the environment. While we may differ on the meaning of this term, it was evident through the narratives of locals – the complicity of humans in wreaking havoc on non-human lives. Emerging towards the end of the documentary is a scene set in the upper-Himalayan village – where a man who sat in the silhouette of low laying streetlight declares humans as an invasive species. While he sketches out a specific design of destruction brought to forested areas earlier meant for wild animals, he foregrounds the complicity of the state – particularly the nature of humans, which allows them to place their ‘interest’ above everything else.

Stapled with such narratives, the impact of intervention in the fragile ecology of the Himalayas is rendered visible through glaring visuals of bulldozed mountains – making roads for Char Dham project and Dams. A combination of voices fraught the documentary – sometimes as lament by elderly women, sometimes of migrants sweeping away stones, thinking of their home far-flung in geographies so different. Documentary humanises the plot of suffering that is either crushed by shining India’s infrastructure or forgotten by enforced amnesia. Documentary pursues the life of river – entangled in stories of human, non-human and a vast sway of memories, fluid, and marsh, vivid and dispersed. It brings us one clarity – the river is never but one thing.

[i] Reference: Naveeda Khan. ‘River and the corruption of memory’.

The documentary will release early next year for the audience outside of India. Siddharth is a kind person who can be reached here for more information: https://sidagarwal.notion.site/Siddharth-Agarwal-18ed4a5ccaae456da931d85b4954b885

***

Rahul Ranjan is a Post Doctoral Research Fellow at OsloMet University.

[…] Read more here: Rivers as Narratives: A review of “Moving Upstream Ganga” – Rahul Ranjan – Doing Sociolo… […]