Ather Zia’s Resisting Disappearance (published by Zubaan Books) is an imperative and urgent text that documents the modes of resistance generated by the women activists of the Association of Parents of the Disappeared Persons (APDP) in Kashmir. Founded in 1994, the APDP strives to draw attention and visibility to the disappearance of nearly 10000 men by government forces since 1989. In the context of continued and pervasive apathy for Kashmiri political self-determination and broader anti-Muslim sentiments under India, Zia’s book contributes to the discourses of gendered resistance, military occupation, memory and archiving, and the constitution of the Kashmiri Muslim woman activist identity.

As her research partners inhabit every day with haunting imaginations of whether the disappeared has been tortured or killed or may turn up alive, Zia explores how mourning constitutes “work”. She asks how do women configure mourning as a political act under military occupation and everyday armed violence? In the absence of possible legal recourse (such as First Information Reports or FIR’s), the work of grief, mourning, and resistance becomes deeply political. Zia eloquently shows that while it is easy to dismiss the struggles of these mothers and half-widows as “poor women crying” (91), their politics reworks the meanings of commemoration, justice and human rights.

Ethnographically invested in the forms of resistance cultivated by the APDP activists, Resisting disappearance has documented the constitution of an “affective politics”, a conceptual thread that connects the entire text and is manifested in different ethnographic artefacts. In the first chapter, titled The Politics of Mourning, Zia concentrates upon the narrative of Zooneh, a mother whose son was forcibly disappeared and who keeps her door perpetually ajar in unceasing anticipation of his abrupt return. The door acts as an illustrative artefact and articulates, “… a haunting, not a figment of Zooneh’s imagination but an interstitial space- of a return, hope, resistance, and a quest for justice” (34). Drawing upon narratives from other research partners, Zia explains how doors and related meanings of arrival, departure and absence intensify for the kin of the disappeared. Zia employs the partial openness of the door and an “analysis of intangibles” to formulate the concept of “affective law”, which stands in emotive defiance to the “sovereign’s law” that has enabled forced disappearances in Kashmir (35).

Zooneh’s mundane practice of leaving the door ajar corresponds to an intense search for her disappeared son, which involves pursuing cases and paying repeated visits to courts, administrative offices and the State Human Rights Commission (SHRC) as well as participating in the activities of the APDP. Zia observes the simultaneity of Zooneh’s suspended grief and her determination to find her son, formulating it as a “hopeful melancholia” (38). The legal and political landscape of injustice in Kashmir hovers spectrally in the text while Zia’s research partners invoke and call upon “other doors” (39) of justice. Zia explains how Zooneh and several other APDP activists are dedicated to visiting shrines for supplications, consulting faith healers such as faqirs and pirs, and fervently adhering to the historical Kashmiri tradition to the meticulous rituals prescribed within spiritual traditions. Resisting disappearance thus observes that every day becomes woven into a “politics of mourning” and into metaphoric and material expressions of affective law where resistive meanings of justice, agency and power are generated.

Zia rigorously documents the articulation and continuous reworking of gendered notions of the agency under the simultaneous presence of military occupation and the expressions of resistance developed by APDP activists. In chapter 3, Spectacular Protest, Zia providesdetailed descriptions of the social and physical organisation of protests, both pre-planned and spontaneous. She explains how gendered codes of propriety are visibly disrupted as women emphatically lead demonstrations in the public domain. The notion of visibility becomes an important concept throughout the text as APDP activists strive “to make visible what had been made invisible by the government” (8).

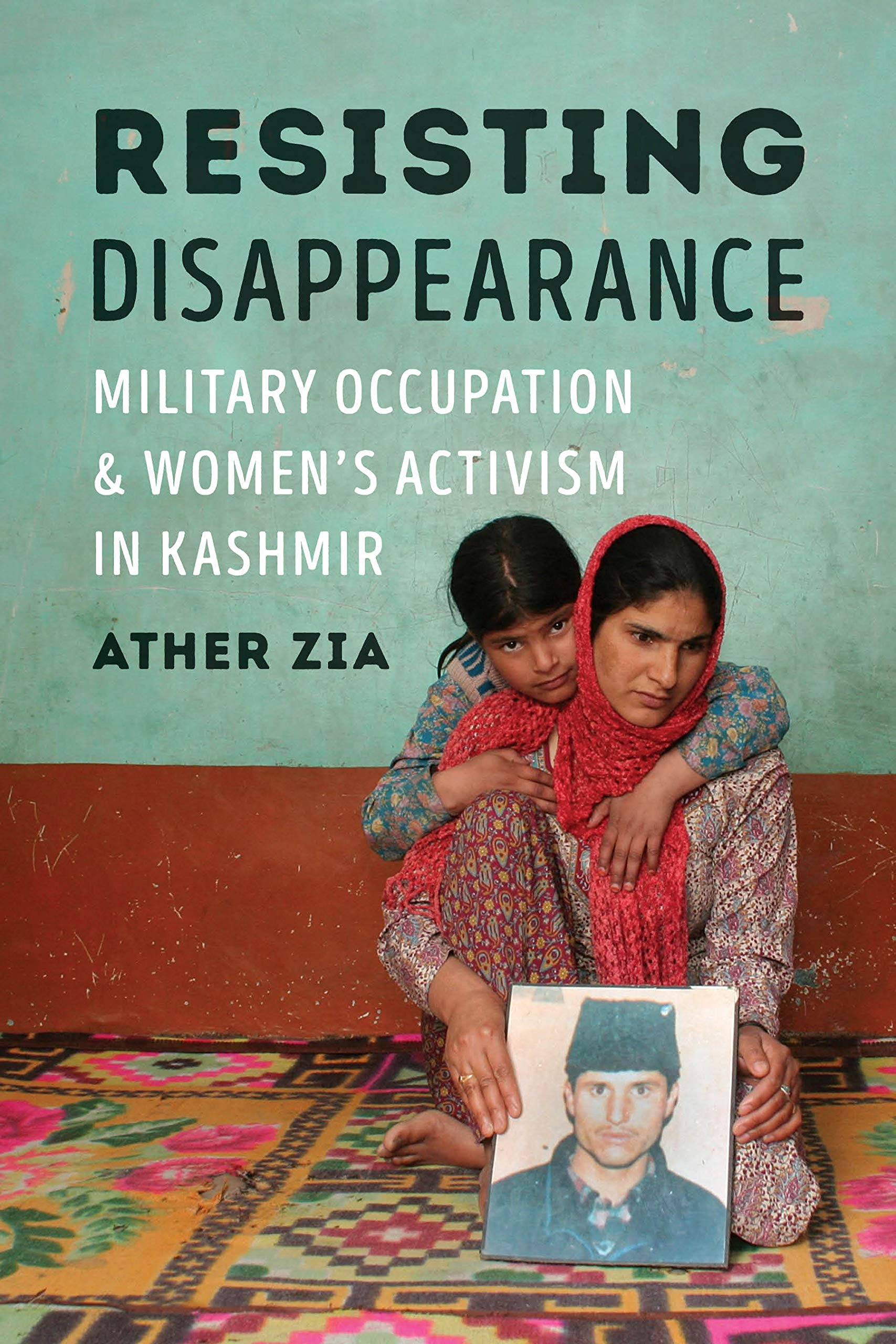

Zia’s ethnography witnesses women’s visibility and conspicuous presence on the streets, in courts, and in locations where the search for the disappeared continues (in army camps and police stations). This public visibility, she explains, does not conform to the notions of an asal zanan (a good woman) – a Kashmiri phrase that signifies attributes such as discreteness and “not being seen or heard” (68). Zia argues that APDP activists mould their “public identity” by “improvising” upon the social order that regulates notions of female respectability and modesty (68).Thus, norms regulating gendered behaviour are not thwarted completely but are reworked to carry out a public and unceasing search for the disappeared. Through tropes as metch (a woman who renounces social norms), shisterr (iron) and buth (“a stern, unrelenting public face”), Zia explains how performative self-descriptions allow activists to emerge from being seen as “just a woman” (76) and to regulate how they navigate the public gaze agentively. Zia observes the age-appropriate and differentiated manner in which the activists conduct themselves while being photographed by journalists and argues, “…APDP activists control how they should be gazed upon” (88). Thus, an activist identity is created while simultaneously preserving the asal zanan.

The narratives of Zia’s research partners echo fierce grief, the depletion of physical and mental health and the pervasive lack of legal options. They also convey the intensity of the search for the disappeared and a corresponding, deep reworking of the self, which is described through tropes of madness and an altered relation to socio-cultural conventions. The significance of Resisting Disappearance also lies in discerning the “nonhegemonic” (86) character of patriarchal structures in the context of militarised violence. As women become the “protectors” of men to shield them from brutalisation by the armed forces, Zia argues that APDP activists represent “a triumph of subalterity within sublaterity” (86) However, Zia does not argue that the work of resisting human rights violations belongs solely to women. Instead, she emphasises the conditions produced by military occupation, under which all genders are at the receiving end of physical and sexual violence, and where the structures of patriarchy experience nuanced yet significant adjustments. This is evident in the statement of Zia’s research partner, Sadaf Khan, who states, “(m)y husband is my human right” (85). Thus, Zia’s engagement with gendered agency explains how the meanings of motherhood and conjugal relations transfigure to sustain the discourse of human rights and justice in Kashmir.

The book explores the layered and manifold formations of Kashmiri subjectivities in the context of decades-long militarised occupation and an even longer history of the Kashmiri struggle for political self-determination. Chapter 5, Militarizing Humanitarianism and Life in the Gray Zone, examines the “goodwill” attempts by the army and reflects upon the paradoxes and ambiguities these create. As the military becomes increasingly crucial to administrative governance in Kashmir, Zia examines various domains of everyday life such as livelihood and professional choices, access to healthcare and hospitals and the private domains of homes and kitchens that become spaces of intimate interactions with the armed forces. This produces dilemmas with “choiceless choice(s)” (115) where social, cultural and economic life becomes enmeshed with militarisation. The remarkable breadth of Zia’s ethnography is noticeable as the chapter also documents the transformations of vocabularies and ordinary discursive selections, thus underlining the structural violence of the occupation. Zia argues that the Kashmiri subjectivities are “palimpsests” (139) and are woven into webs of compulsion and reluctance where actions are to be read through layers of political and historical contexts.

With deep anthropological insight, Zia delves into how meanings transform under an every day of violence and brutal subjugation by government forces. The most noteworthy chapter documenting this is chapter 6, Archiving and Embodying the Disappeared. The longest in the book, this chapter deals with how resistance and forms of counter-memory cultivated by APDP activists transform the meanings and interpretations of the archive. Zia located an “ethnographic presence” (149) in the file- a ubiquitous presence in her fieldwork and carried by all her research partners. The file comprises numerous documents such as birth certificates, school diplomas of the disappeared. While it contains administrative paperwork involved in the search for the disappeared, it always lacks the FIR. Bureaucratic engagements are found in the file only in “deferred perusals” (161) and continuous referrals. Zia explains that while the file does not possess documents that could constructively contribute to a legal case, the file becomes a “form of truth” and “an artefact laden with effect” (149) Zia’s research partners repeatedly utter the phrase “documents talk”, thus opening up an inventive feminist exploration into the meanings of bureaucratic paperwork and legal documentation.

The significance of Zia’s extensive engagement with the archive lies in the fact that in a legal and political climate where the disappeared and the veracity or evidence of the disappearance are both obliterated from the record (33), she locates the spaces where memory is preserved and guarded. Zia observes the locations where the file is kept (rather hidden) and how it is carried protectively by her research partners, thus explaining how documents occupy spaces of material and discursive absence. Zia explores the “body archive” (164) as mothers and half-widows articulate loss, memory, mourning in embodied forms and the form of pain inscribed upon their bodies. As APDP activists gain public visibility and are extensively photographed, recorded and quoted, they become part of the archive. Zia also locates memory in affective transmissions across generations as children, who have never met their disappeared fathers, inherit and experience trauma, thus inhabiting “postmemory” (44). The gendered resistance manifests in these practices of preserving arbitrary documents and in preserving pain in their bodies, where Kashmiri women preserve memory as “historical subjects” (187) excluded from the domains of the official record and formal justice.

The book is ethnographically dense, and scholars invested in militarised occupation, feminist resistance, and the archive and commemoration in the everyday would find this book valuable. Zia’s ethnography is elegantly supplemented with her poetry. While she does not claim to be a “native anthropologist”, her long-standing experience as a Kashmiri activist has undoubtedly added intellectual and poignant sophistication to the text. Zia draws parallels with women-led struggles across the globe- such as the Madres de Plaza Mayo in Argentina (9) and Irish women protecting Irish Republican men against British atrocities (95), thus producing an elaborate and indispensable anthropological account of Kashmir, the most militarised zone in the world. The text converses with the Foucauldian notions of power, agency and micropolitics (69). Also, it draws upon Jacques Derrida’s scholarship to explain the spectral character of the law and the politics of the archive. It is, however, very lucid in style and structure and stands as evidence of Zia’s deeply reflective and introspective scholarship.

***

Amna Majeed is a PhD Scholar at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta. She is also a Fellow at the MediaArts Lab, Agastya International Foundation.