(Source: The Guardian)

Men and feminism are often seen as being intrinsically at odds. Feminist struggles and academic discussions might have been more inclusive and nuanced, but the popular narrative of the incompatibility of men with feminism persist. Feminism is even seen as anti-male.

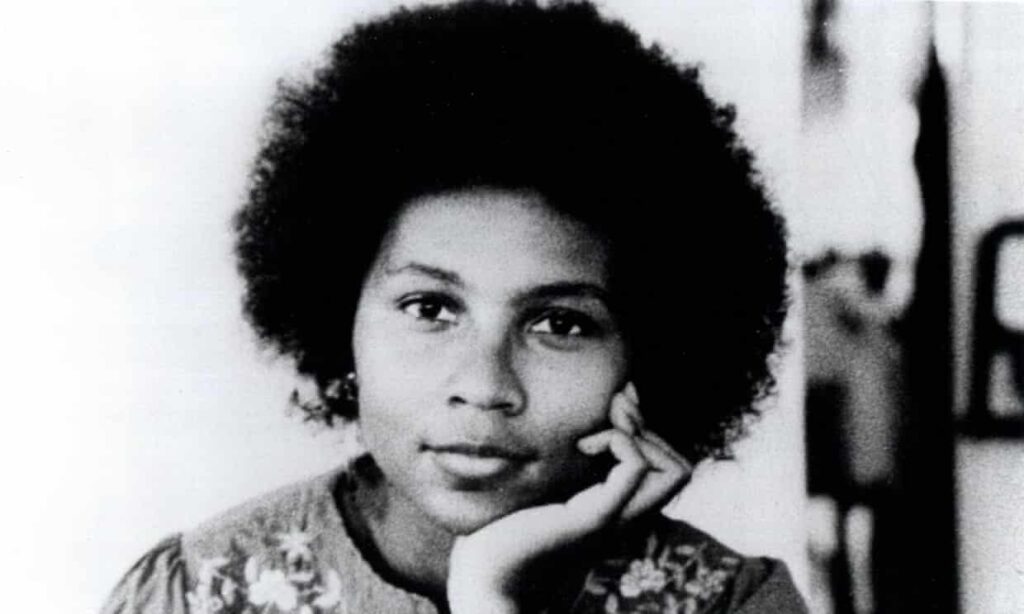

As for myself, I am still searching for the feminism that I read in books and articles. Literature does perform a role reasonably well, and that gives hope. I am averse and attracted to reading for this single reason, i.e., it’s tough to find that optimistic image in society, but at the same time, it’s hopeful that there are people who have this vision for society. bell hooks was one such person. I turned to read her work The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love – not for her iconic role in black feminism but because of my concerns as a man.

bell hooks drew her experience of males from her family of orientation and, later, the family of procreation. Her father was a crucial figure in shaping her understanding of males in society. An emotionally crippled man, who fears showing affection, vulnerability and mistakes are what she talks about when she refers to her father, who happens to be a war veteran. She goes beyond the strong, dominant and intimidating male figure to reach out to the little boy beneath, who once cried when he was sad, jumped to hug his parents when joyful and didn’t care if he liked anything that was socially perceived as feminine.

hooks investigates this journey of a boy who is socialised into a man – a patriarchal man. She argues that when males are excluded from feminism or are seen as enemies by radical feminists, the feminist revolution weakens. She holds patriarchy accountable for the oppression of females and males instead of males. She introduces a dominator model, upon which patriarchal structure stands. This dominator model compels a person to believe that the only way to survive is domination – of females, males and children.

She gives anecdotes by different authors in their works of how the patriarch of the house bursts into a rage when he is in a position of vulnerability, weakness, making mistakes or simply not knowing something. According to hooks, the dominator model does not let the patriarch accept these human tendencies, making him less human. It makes the person emotionally disconnected from themselves. Consequently, the person becomes a stranger to the emotions such as sadness, grief, amusement, anxiety, boredom, joy, nostalgia, fear, etc. However, he is familiar with one, which is anger, which translates into rage and violence. hooks highlights this by drawing on Terrence Real’s words,

“When I first began looking at gender issues, I believed that violence was a byproduct of boyhood socialisation. But after listening more closely to men and their families, I have come to believe that violence is boyhood socialisation. The way we “turn boys into men” is through injury: We sever them from their mothers, research tells us, far too early. We pull them away from their own expressiveness, from their feelings, from sensitivity to others. The very phrase “Be a man” means suck it up and keep going. Disconnection is not fallout from traditional masculinity. Disconnection is masculinity (pp. 61).“

hooks says that the mass media and popular culture normalises this male rage. Movies and shows glorify destruction as the only solution. Boys are socialised into these fantasy worlds by franchises such as Marvel Universe. If destruction cannot be served directly on a platter, then domination is latently used. She critiques the Harry Potter series where death and killings by a teenager are normalised. The good and evil binary does not leave any space for empathy. As per hooks, any other male author would have been held accountable by the feminists if it was not J.K. Rowling.

The socialisation of boys into the isolation of the fantasy world and gaming instead of expression and communication creates men who are emotionally handicapped. They do not know how to express their emotions or interact with the other gender. It is not that this dominator model is upheld only by men. As much as men are not ready for powerful women, women are not ready for emotionally sensitive men. hooks narrates her own experience, how she was very uncomfortable with her long-term partner expressing his emotions and vulnerability because she felt her safety threatened. She says that women are not ready to face the cracking of the façade of the male protector.

It is not to be assumed that patriarchy has less impact on the families where the male-female dynamic is absent. Even among gay couples, the carrying of masculinity by gay men is similarly imposed. The women who have financial independence and are powerful also impose their dominance as any male does. Women who have assumed powerful positions have adopted emotional distance, disconnectedness, and manipulation of a man. There is always a dominator who is emotionally absent and trades of this incapability with the role of a provider.

Even in single-mother families, patriarchy holds its ground effectively as the mother feels the need to be stricter with the children. It is observed that single-mother households witness the harsher treatment of children by their mothers because she feels the need to incorporate the masculine within the male child. Hence, the family becomes a site of constant conflict because the boy feels a power injustice he is supposed to be accorded as a male, but the mother holds that power in the house.

hooks does not refer to patriarchy simply by itself. She calls it “imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy”. The Indian subcontinent has been culturally heterogenous where most men have not strictly conformed to “imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy”, but patriarchy has been prevalent. Gandhi’s embracing of the effeminate Indian man in British colonial India was a political response to “imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy”. While Gandhi is not always accepted as a feminist, his espousal of the emotional side did pose a good counter to the masculine British colonialism.

With the rise of radical Hindu nationalist identity, one of the responses to colonialism recognized by Ashis Nandy, the country does seem to be vulnerable to “imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy”. Nonetheless, male role models are needed to bolster an emotionally sensitive male identity and champion a feminist identity, thereby including males in the feminist revolution.

References:

hooks, b. (2004). The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love. First edition. Washington Square Press.

Nandy, A. (1989). The Intimate Enemy: Loss and Recovery of Self Under Colonialism. Oxford University Press.

Connellan, M. (2010, January 28). Women suffer from Gandhi’s legacy. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2010/jan/27/mohandas-gandhi-women-india, accessed on January 7 2022.

***

Aman Kumar is a masters student of Sociology at the Centre for the Studies in Social Systems (CSSS), Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi.

… [Trackback]

[…] Informations on that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Info here to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More here on that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More here to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info on that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 74032 additional Info to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Info here to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you can find 46322 more Info to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on on that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More here to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Information here on that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Info here to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info on that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info on that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information on that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 68255 more Information to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information on that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 29626 more Info to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 76379 more Info to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you can find 28246 additional Info on that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 28642 more Information to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

Paket Tour Blue Fire Ijen

… [Trackback]

[…] Info to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More here to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 86479 more Information on that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

Paket Tour Baluran National Park

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Information here on that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 90245 more Information on that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you can find 77300 more Information on that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you can find 87919 more Information to that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 2746 additional Information on that Topic: doingsociology.org/2022/01/23/remembering-bell-hooks-and-her-gift-to-men-aman-kumar/ […]