Sociology is the study of society. The description runs the risk of creating more confusion; than clarity. There is no clear answer to the question – what is society. Society is an abstract concept to the extent it gives license to sociologists to study an economic institution; as well as democracy, a political system of governance. However, such a license does not imply chaos. When a sociologist approaches an institution, event or phenomenon, as an object of sociological study, she investigates it as part of social mechanisms. In this essay, we thus explore the adjective – the social. Even if we cannot locate society tangibly, it is possible to bracket and describe the realm of the social. The claim is that the social is a specific human condition of living.

Historicizing the social

The social, as a realm of human existence did not exist from the beginning. It is a product of the historical development of human intercourse. Karl Marx insists on the social aspect as the foundation of human existence. For him, labour is a human attribute par excellence (Marx 1964). Animals receive nature, as it is. They eat what nature provides them with. Even if, a bird builds a beautiful nest, it can only do so with resources already there in its natural surroundings. On the other hand, human beings, with their ability as a labourer can transform nature and bring new elements into existence. For example, humans can learn how to create fire. But it does not stop there. Once they find metal, they now can manufacture weapons. Fire and metal come from nature. But a weapon is a human creation. A weapon is also a technology. Once, human beings used it to hunt animals for their survival and sustenance.

Technology is an instrument, that aids in human activity. It reduces the requirement of labour-power. With advanced technology, human beings can exploit natural resources more efficiently, produce on a greater scale and meet diverse human needs. In Marxism, natural resources, technology, and labour-power, taken together, are called productive forces. Alongside advancement in productive forces, Marx argues, new needs – besides basic needs of survival and sustenance – came into being. Our mastery over nature also allowed an increase in population. So different groups of individuals could assume the responsibility of taking care of various needs. This is what is called division of labour. The first such division is the sexual division of labour between men and women. However, Marx also argues, division of labour is not merely about production and thereby satisfying human needs. Division of labour is also cooperation between groups of human individuals. In other words, this is the emergent moment of social-human cooperation and association as a condition of living (ibid).

A century later, Hannah Arendt (1998) would critique Marx for his sole attention to labour as human activity and his preoccupation with survival and sustenance. For Arendt, labour is one of the human activities; and crucial for human survival and sustenance. However, true human activity is to live among and with the others – our public existence. She draws our attention to Greek ‘society’; and argues that Greeks had no concept of society. There was no realm of the social. Greek ‘society’ was divided into oikos (private) and polis (public). In the private realm, a man is supposed to take care of his family and fulfil all the needs and necessities. However, this is merely a condition to join the realm of the polis. In the polis, free individuals gather in public to discuss questions on – what we will refer to today as – political, philosophical ideas and ideals. Interacting with other members of the polis – acting, speaking and communicating – was the only true basis of the human condition of living.

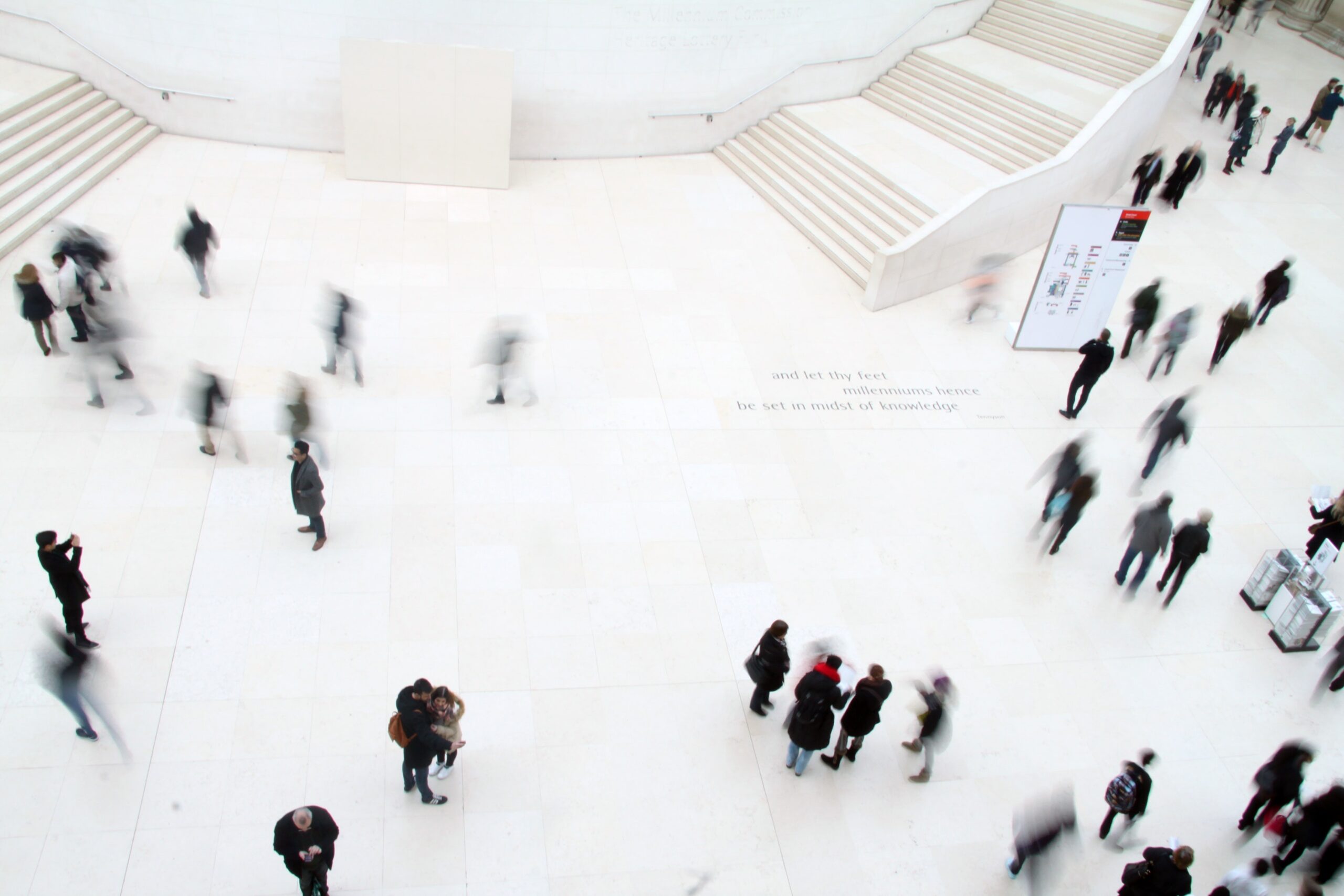

Over the centuries, however, the domain of the private has become more important. With the rise of the nation, the private has come to constitute the public. Today nation is thought of as a big family. The human condition of living – as interacting and communicating with others – is replaced with the living with an anonymous mass. Despite the anonymity, we share common interests – survival, sustenance, economic prosperity etc. Not surprisingly, the state resembles the head of a family.

Thus, Arendt suggests that one way of understanding the social condition of living is to pay attention to our existence within a nation-state – a supra-family. The validity of Arendt’s observation is rather easy to demonstrate. Think of nationalism as a discourse. In the name of a nation, we are asked to believe in one flag, one anthem, one set of values, one common Indian culture etc. Politicians are always talking about the growth and economic upliftment of our nation. India is a name of a nation-state; also, a name of a mass society – with shared beliefs, values and ways of living. And finally, imagine our existence in our family – common descent, values, and a head of the family, preoccupied with monthly income.

Disregarding the major differences between Marx and Arendt, we see, they agree on two fundamental issues. First, both trace the history of the emergence of the social. It came about in one particular moment of human history. For Marx, it dates back to the very beginning. But for Arendt, it is rather a recent phenomenon stretching back to the 16th century. Second, they don’t conceptualize the social as merely a group of individuals. The social is a specific mode of coming together – for Marx, the foundation of the social is division of labor; for Arendt, it is family.

The social as the relationship between the individual and collective living

Both Marx and Arendt also explore another dimension of living in a society – how collective living influences an individual and his psyche. The relationship between individual and collectivity is also central to the sociology of Emile Durkheim. Durkheim (1995) considers society a sui generis entity. Like Marx and Arendt, Durkheim also refuses to assign any human gathering the status of society.

There is a distinction between a crowd in a railway station and an audience in a rock concert. Both have an objective. In the former case, along with others, one is waiting for a train; in later, one is there to enjoy a performance. However, anybody – who has attended or seen a crowd in a rock concert – can point out a distinction. There is a palpable collective energy, almost euphoric, in a rock concert. The force of energy seems to be all-pervasive and infecting everybody, including the rock stars.[i] No such energy is ever-present in a railway station. Durkheim argues that society has a similar effect on our psyche. To live in a society means to be always aware of ‘something’ bigger and greater than us, exerting a force on us, from outside (Durkheim 1982). This phenomenon – something outside and coercive – is precisely what ‘social’ condition of living. Durkheim (1995) equates society’s power over us with that of God. In fact, he argues God is nothing but society. We don’t know, beyond doubt, whether or not God exists. Similarly, we cannot see society. But it does not matter. God exists because we believe. Society exists because we feel it within.

How does society come to have such power over us? An answer may be found in the works of Max Weber (1947).[ii] Weber is not interested in a large collective. Weber attention is focused on those moments in our everyday life when we think in our head: ‘what others will think?’. He argues the social is that aspect of our life when we act keeping in mind the other’s actions. Most of our activities – from overt actions to simple acts of thinking – are governed by our interpretations of others’ actions. Someone gives you a pen on your birthday, you know it to be a gift. You thank her. Maybe, you reciprocate her action by giving her a card on her birthday. However, the situation may become very confusing, if someone gives you a pen on an ordinary day and without any occasion. Nonetheless, in everyday life, most of the time, such confusion does not arise. Because we are social. We share our existence and experience in a way, that most of our actions make sense to another (meaningful), even to a stranger (Guru and Sarukkai 2019). Thus, society is indispensable for an individual to go about smoothly – acting, interacting and communicating meaningfully – in everyday life. It may explain why society has such power over us. The phenomenon is also described as intersubjectivity (Berger 1963). Imagine a huge net. And we are living on top of it. The net is the base beneath our feet. Social living is like that.

The Critical school, especially the work of Herbert Marcuse (2007) probes the relationship between society and individuals more deeply. As compared to Weber, their view of our collective living is more critical and even pessimistic. Inspired by Marxism and Freudian psychoanalysis, they wish to show, our sense of self and individuality may be governed by the social forces more intensively than we fathom. They emphasize ideology – one aspect of Marxist scholarships that we have not mentioned so far.

The reality of ideology in Marxism may be compared with Durkheimian notion of the relationship between society and psychic life. In Marxism, ideas correspond directly with class relations.[iii] The set of ideas, widely shared and believed is ideas of the ruling classes – economically and politically dominant groups. They need ideology to protect their dominance over the dominated classes. The set of ideas often determines not only our shared beliefs and ideas but also who we are (see Althusser 2006).

Advertisement is a good example here. We all watch advertisements. We don’t take it very seriously. However, Marcuse will argue, they have a deeper effect on us than we think. For example, often we prefer to buy a pair of sneakers, manufactured by a ‘reputed’ brand over a local brand. In most cases, the reputation is created; and a false idea. We consider it ‘reputed’, because it was worn, perhaps by our favourite cricketer or a celebrity. It is widely reported that sneakers, manufactured by big brands are made in third-world sweatshops, no different from our local shop. There may as well be, in all practicality no difference between branded and non-branded sneakers.

Nonetheless, our desire for the former, Marcuse (2007) will argue is created by the brand companies. No one will deny, that having a sneaker is a basic need. We need it to step out of the house or to play cricket in the evening. But our desire to buy only a branded one is a false need – we are made to believe that we need that brand. This is how, desire, liking or preferences – which we believe solely ours – are socially produced, a condition of living in a capitalist society.

The social as changing condition of living

We have seen the social is historical. The social is, in essence, the relationship between individual and collective living. Then the social can also be understood by comparing human existences in different periods. Zygmunt Bauman, among many scholars, explores this dimension in his scholarship. He refers to contemporary times and our existence in them as a postmodern condition of living. He argues. to live in a postmodern world is to live with a fluid identity (Bauman 1996). Identity is the conception of our location in a society; and vis-à-vis other members of a society. In a modern capitalist society – howsoever critical Marcuse is about it – one still has a stable identity. Stability in the conception of our location is supremely important. Because if such stability is not there, it makes our existence anxious. We can think of our names. It is an important aspect of our life that we are often oblivious of. But think of a situation – one offers you one crore rupees to have no name. Most of us will not even agree to do so. Because if we don’t have a name, we don’t even exist. This is however an extreme example. Bauman, on a more modest scale, argues that in modernity we wanted a solid identity. However, in contemporary times, we want to escape it (ibid).

For many of us, our parents want to settle back in the place, where they grew up. But many of us may not have any such desire. We may have grown up across the world as our parents took jobs in different cities or countries. We have no attachment to a particular place. Thus, we do not need to identify with a city or country as our own. Bauman also argues, this is intricately linked with how our social life around us is. We live in an age where information technology can link us with any part of the world in no time. A software company can send you to another country where they have an office within a short period of notice (see Bauman 2006). These have become part and parcel of our lives. We don’t even think about it in our everyday lives. But a moment of reflection shows that our non-identification with a place is intricately connected with the fluidity of our existence in the virtual and real-world, as we have just discussed.

The anxiousness – such condition of living causes – opens ourselves to risks. Today, we live in a risk society (Beck 1992). Because we don’t settle in one place, we also lose connection with our relatives, friends or a community, that we grew up with. Thus, any crisis in our life is solely our crisis. There is no safety network of relatives or friends. Think about your friend who lives in a foreign country among people whose way of life or culture is completely different from hers. She in all practicality lives among strangers (even if she has made friends or acquaintances). Far off from family and relatives, during the COVID-19 crisis, she may as well be locked up in a house with the looming threat of losing jobs. But even if her family wants, it is difficult to extend care and comfort in such a trying time. It is this risk; we all take in today’s world all the time.

Conclusion

To conclude, the essay thus completes a circle. Arendt argues, the social emerged with the rise of the nation-state. We end with a scenario, where we have transcended such national boundaries. However, there is a common thread that still runs through the history of human existence and the study of it. Arendt also argues with the emergence of the social, we invented a sphere of the intimate. Within a home, we always try to find a room or space, which we may call our space. It is our refuge solely belonging to ourselves. We like to do what we feel like in that time within that space. A father or mother’s supervision is relaxed there at that moment. Arendt believes, in a scenario similar to that we created a space called intimate within our ‘self’, away from the gaze of the society. If we pay attention, this theme is being explored even today by contemporary sociologists. Even more than ever, they seek to understand society and the social with a category called subjectivity: an individual’s ‘agonistic and practical activity of engaging identity and fate, patterned and felt in historically contingent settings and mediated by institutional processes and cultural forms’ (Biehl, Joao, Good, Byron, & Kleinman, Arthur 2007: 5).

References:

Althusser, L. (2006). Ideology and ideological state apparatus (notes towards an investigation), in Lenin and Philosophy and other essays (pp.85-126), (trans. B. Brewster). New Delhi: Aakar.

Arendt, H. (1998). The human condition. Chicago, US: The University of Chicago Press

Bauman, Z. (1996). From pilgrim to tourist – or a short history of identity. In S. Hall and P. Gay (eds.), Questions of Cultural Identity (pp. 18-36). London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Bauman, Z. (2006). Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Beck, U. (1992). Risk society: towards a new modernity (trans. M. Ritter). New Delhi: Sage Publications Ltd.

Berger, L. P. (1963). Invitation to sociology: A humanistic perspective. New York: Anchor Books.

Biehl, J., Good, B., and Kleinman, A. (2007). Introduction: Rethinking Subjectivity. In J. Biehl, B. Good, A. Kleinman (eds.) Subjectivity: Ethnographic Investigations (pp. 1-24). Berkeley: The University of California Press.

Durkheim, Emile. (1995), Elementary forms of Religious Life, translated by Karen E. Fields, New York, US: The Free Press.

Durkheim, Emile. (1982). The rules of sociological method (trans. W. D. Halls). New York: The Free Press.

Guru, G. and Sarukkai, S. (2019). Experience, Caste and Everyday Social. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Marcuse, H. (2007). One-dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society. New York: Routledge.

Marx, K. (1964). Selected Writings in Sociology and Social Philosophy (trans. T.B. Bottomore). New Delhi: McGraw-Hill, Inc.

Weber, M. (1947). The Theory of Social and Economic organization (trans. by A.M. Henderson and Talcott Parsons). Illinois: The Free Press.

[i] The rock stars do depend on the energy of the crowd to energize their performance. This is why, a rock star’s efforts to involve the crowd during performance is a common phenomenon. Durkheim gestures towards the same phenomenon with the example of an orator on stage and his listeners.

[ii] It does not imply that Durkheim does not have an answer to the question, posed above. However, we are interested in exploring the dimension of social from multiple perspectives.

[iii] Classes and class relations are matured form of division of labor and human association in societies such as ours. They are determined on the basis of which group owns technology; which group owns labor power and so on.

***

Anubhav Sengupta is an Assistant Professor in Sociology at the Manipal Centre for Humanities.