The “love, sex aur dhoka” genre unfolds chillingly in Amazon Prime Video’s recent offering, Dahaad. Directors Reema Kagti and Zoya Akhtar capture the vexing anatomy of caste while laying bare the vile face of misogyny in the hinterlands of Rajasthan. At its core, Dahaad is a police procedural drama without the unnecessary frills of a high-speed car chase or unexpected reveals. Instead, the culprit is hidden in plain sight. The audience suffers the anguish of waiting to see the serial killer (a wisdom-dispensing, mild-spoken, Hindi school teacher) target his next “kill”. Contrary to the Bollywood fetish of a chronic Savarna saviour complex (Article 15, Swades), the female police officer who has been put in charge to lead the case is from a backward caste. Her struggles in a context of entrenched patriarchy and caste discrimination are palpable- from the hooting of young men to see a ‘lady’ cop in pants to the everyday casteist taunts of her male superiors. She also has a mother whose only desire is to see her daughter married. She occasionally summons potential grooms and their families to meet her cop daughter. The outcomes of those meetings are inevitably unsuccessful in making an alliance. Thankfully, her boss is sympathetic and is a rather unusually tender man in the badlands of virulent masculinity.

The series opens with a routine investigation of a made-up ‘love-jihad’ case- a Hindu, upper-caste girl has been allegedly enticed by a Muslim man. The men of the girl’s family who also happen to have an influential political clout orchestrate this case to draw anti-Muslim support. Amid this chaos, another story of a missing lower-caste woman surfaces. Investigation of one disappearance leads to another. The investigation unearths a series of women (all from backward castes and low-income families) who have been poisoned and left dead in public toilets. A persistent indifference of the law enforcement authority to file the missing reports of these women has emboldened the killer. In many cases, the families of these women never reported the disappearance since runaway (unmarried) women in rural India are damned if they flee and doomed if they don’t.

The final scene where the woman police officer asks the culprit of his obsession to con innocent girls with a promise of marriage and then poisoning them eventually, is unsettlingly blunt. The culprit declares that his young women victims are not “innocent” by any means; “do innocent girls spread their legs apart for a stranger?”, he asks. There is no remorse; only rage and arrogance of an upper-caste man for these women whose only crime was to be desired and loved.

Also noteworthy is the recurrent social maligning of the women who have allegedly eloped with their partner of choice. In most cases, these are women from backward castes and lower-income households who struggle to pay dowry. Unsurprisingly, the mothers of the missing daughters lament the erosion of social respectability as a result of the elopement. They wish that those runaway daughters never return since all they can bring home is shame and embarrassment. As an audience, we see the discomfort on the leading police officer’s face. She too has been asked about her marital status several times during her procedural rounds.

The Slow Dance of Demography and Patriarchy

What is difficult to neglect in this taut crime thriller is the geographical setting of Rajasthan. In fact, the opening montages portray an effective dance of gender, demography and patriarchy. There are silhouettes of women talking, laughing and going about their lives but they remain invisible or missing. To be sure, the demographic narrative of “missing women” is well-known in the northwestern states of India. The word, “missing” is often credited to the noted economist, Amartya Sen’s seminal demographic commentary in the New York Times Review of Books (December, 1990). His alarming prediction that shook the scientific community was that about 100 million women are missing from Asia alone. By “missing” he meant excess female deaths, victims of nothing other than their sex. Since biology favours girls after birth, typically, in the general population women should outnumber men (a demographic phenomenon that is common in the developed countries). Sadly, the persistence of gender inequality in terms of survival (or ‘missing’ women) is still a story of contemporary India. The Census (2011) indicates that the sex ratio is 926 females per 1000 males in Rajasthan which is below the national average of 940 (an already skewed number). In fact, Rajasthan’s sex ratio has remained chronically adverse over the past decades, improving only marginally from 921 (per 1000 males) in 2001 to 926 in 2011. Pre-natal sex selection, female infanticide and mistreatment of young girls (which includes nutritional and health care discrimination) are often cited as possible explanations for this pervasive demographic imbalance.

Unwittingly, Dahaad (literal meaning is roar) reverberates this demographic reality. A longstanding body of demographic scholarship has noted persistent female neglect and social devaluation of girls/women in the northwestern states of India. In fact, economic development, rising incomes and overall reductions in family size have resulted in a deepening of this trend. Demographers have empirically shown that the female demographic disadvantage has worsened with rural areas gaining access to pre-natal diagnostic technologies, and family planning initiatives that encourage couples to have fewer children. Predictably, the social logic of fewer children demands the presence of one or more male children in patriarchal contexts.

Crucially, dating and elopement are considered impossibly dangerous for young women whose bodies and sexual lives are regulated within the bounds of caste-appropriate marriage. The smooth-talking perpetrator in Dahaad capitalizes on this social anxiety. The victims are found to have had sexual intercourse before their alleged suicides. This makes these deaths socially ignominious. It is a defining imagery of caste and gender oppression undergirding the social suffering that shapes the lives of lower-caste women from poor households throughout their life course. As such, the perpetrator’s caste assertion remains subtle throughout but firmly lodged in the gender-caste nexus. Historically, lower caste women’s sexuality has been constructed as transgressive and are deemed promiscuous, making their bodily appropriation not only “easy” but also justifiable in a caste society. Film Companion’s, Rahul Desai, puts this caste dichotomy of in/visibility ominously well. He notes, “Just as his victims are invisibilized by their lack of privilege, Anand [ the serial killer] is camouflaged by his privilege”

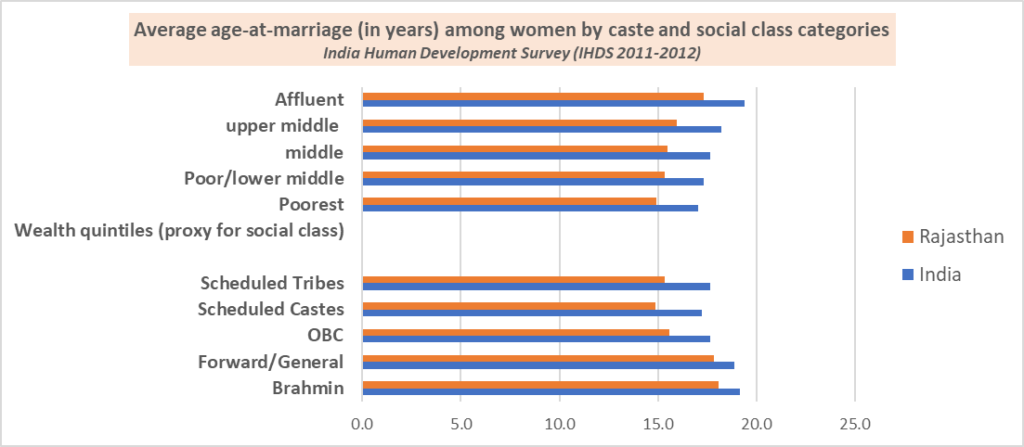

Meanwhile, the centrality of marriage (and by that extension dowry payments) in the lifecycle of Indian women (regardless of their social class and caste affiliations) has been well documented in academic scholarship. Marriage confers social status for women and an extravagant dowry shores up respectability and social capital for women across caste and social class lines. In fact, studies show that generous dowry payments are associated with reduced marital violence in India. These disturbing practices make both (early)marriage and dowry almost compulsory. This perhaps explains why age-at-marriage for Indian women show marginal variations across caste, religion and social class.

The only parameter that tips the scale is women’s education, particularly college education. Recent estimates indicate that women with a college education marry later and are more likely to choose partners who have similar educational backgrounds (a demographic phenomenon commonly known as education hypogamy). It can be expected that such women will enjoy greater autonomy in marital transactions- both material (dowry) and nonmaterial (partner choice).

Dahaad’s social messaging is not a timid one. In a way, it shows how the demographic landscape can be both an outcome and co-option of patriarchal violence against women. It is a powerful reminder that all the uproar about smashing the patriarchy in woke circles can be reduced to a whimper unless social institutions of marriage and family are adequately challenged.

***

Tannistha Samanta is an Associate Professor of Sociology at FLAME School of Liberal Education, FLAME University, Pune.