The notion of grief is both time-bound and timeless- to grieve is to be stuck in the moment of loss and at the same time, befriend the pain that comes with it till the very end. This notion is so universal yet understanding its imagery is intriguing to many. There is no better way to understand this idea in the domain of visual arts, other than the expressionist movement. While art has always been associated with being a catharsis for pain, it wasn’t until this era that artists depicted the “ugliest” nuances of human emotions. Wassily Kandinsky and Van Gogh, among many others, concerned themselves with the exploration of the darkest aspects of the human psyche. One such artist, Käthe Kollwitz, presents an earnest and unique portrayal of grief.

Born in July 1867, Käthe Kollwitz was a German printmaker and sculptor. Although she was initially engaged in painting, she started producing etchings and lithographs after being heavily influenced by the prints of Max Kingler (Turner, 1995, p. 205). From the “Mother protecting her Child” Series to “Death” and “War-Never Again”, notions of emerging worker’s movements and social commentary were predominantly present in her works, along with ideas of mourning and longing for death. As an activist, she participated in petitionary actions against the Nazis which caused her to be removed from the Academy of Art and lose her studio. Amidst socialist movements, wartime anxiety and trauma Kollwitz produced her series “The Weaver’s Revolt” of sheet 1- Need. The series was inspired by Hauptmann’s play “The Weavers” based on the Silesian weaver’s uprising of 1844 against wage exploitation and reimagined a revolt against bourgeois oppression.

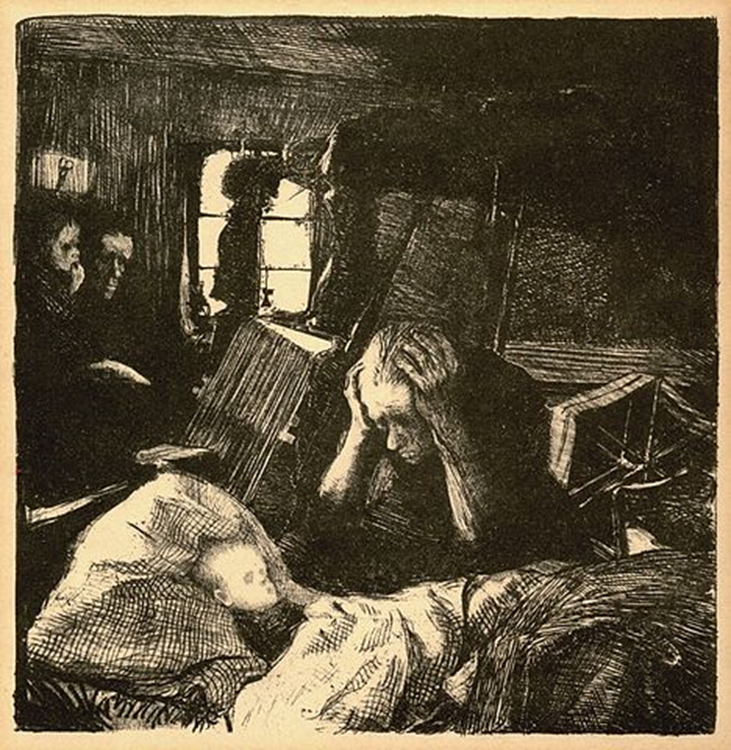

Need, sheet 1 of the cycle “A Weavers’ Revolt”, 1893-1897, Kathe Kollwitz

The piece is made through the medium of lithography which not only allows for a stark contrast of monotone colours to appear but also grants a unique illustration of movement. The bluntness of the graphic lines heightens how the beholder perceives emotions because their presence is so exigent that they cannot help but confront them. This generates a sense of queasiness because it touches upon the truth. Through the dark lines Kollwitz “draws, tears open, rends, marks and scarifies” (Kolb, 2018, p. 313). Darkness proliferates throughout the room leaving almost no space for light, as grief makes its presence known. Here, the colours represent the increasing and ever-growing sense of distress that seems to be consuming the figure- thus in observing the colour itself, the audience also absorbs the figure’s internal emotions.

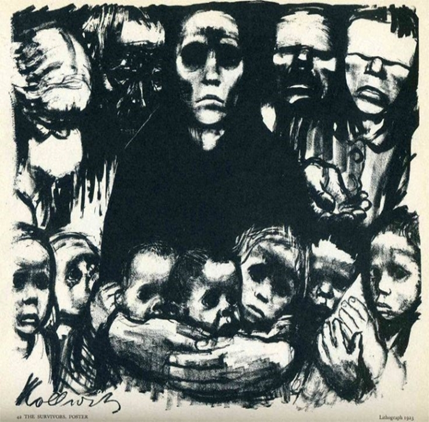

In Kollwitz’s works, the themes of death and mourning are accumulated in the individuals or the subjects of the work themselves. Through the presence of skulls, corpses, or surviving witnesses (p. 306), Kollwitz attempts to personify the notion of death and mourning. In “Need”, through the iconographical image of a mother in despair, grieving over the death of her sick child, Kollwitz accumulates notions of death and mourning in the subjects. In “Personification: An Introduction”, Melion and Ramekers et. al. (2017) argued that such personification as an iconographical tool allows for something which is not human to be given a human identity or “face” (p. 1). The body, both living and dead, becomes the standpoint of the embodiment of grief as the expressions, hollowed faces, bodily gestures, or stillness of the figures- all personified characters come to portray how grief can be visualized. The idea of death also manifests as a symbolic corporeal haunting figure in the background, eminently marking its presence. This blurs the lines of tangible reality and concepts, making the abstract idea of death and mourning succinct, stressing it’s otherwise looming sense of urgency.

Such notions of personification were quite prominent in the works of other expressionist artists of the time. Edvard Munch’s shouting head figure in “the scream” illustrated “a death’s head” (Gombrich, 1995) while in Ernst Barlach’s “Have Pity!” intense expressions are captured in a beggar’s hands (p. 370). However, what is interesting and perhaps distinct in Kollwitz’s work is that this personification was also gendered. Most of her works elucidate grief with mother-child imagery by undertaking women as the face of mourning. This is evident in “Woman with Dead Child” and “The Survivors”. In “Need”, this is reiterated and becomes even more succinct, with the imagery of a mother in despair witnessing the death of her child, with another woman in the background holding her child. These pieces have also been inspired by events that transpired in her life. Her diaries reveal her own experiences with mourning the loss of her son and grandson, both of whom died during the war. At the same time, her letters express inner turmoil, uncertainty, and questions of sacrifice in war (Moorjani, 1986, p. 1110).

During the time, ideologies that emphasized the sacrificial strength of women were proliferating as many socialist leaders vocalized the importance of mothers accepting the bloodshed of war for the “greater good” (p. 1110). Although much of Kollwitz’s writings and initial works indicate her affiliation with similar dogmas (p. 1111), pieces such as “Need” are said to have challenged them through their pacifist illustrations in many ways. Through her portrayal of a woman who has been deeply disturbed by the event and is unable to accept it, Kollwitz subverts as well as problematizes the romanticization of sacrifice. She places women as vulnerable individuals who cannot or should not be expected to immediately accept and let go of the unimaginable experience they have been dealt with. In doing so, she validates a specifically feminine expression of emotions that were often muffled with the expectation of suppression. This is crucial because the portrayal of grief in her work cannot be separated from the discourse of maternal loss and a definite feminine perspective.

When placing Need, as sheet 1, in the series of “The Weaver’s Revolt”, we connect its individualistic or autobiographical notion of mourning to larger proletariat struggles. It confronts “difficult themes of poverty, infant mortality, violent rebellion, and retaliatory slaughter” (Prelinger, 1992, p. 21) This adds multiple dimensions and layers to the experience of grief as presented in “need”, as it is not only maternal or feminine but that which has emerged out of a specific oppressive struggle. Kollwitz became exposed to the struggles of the working classes, from poverty to unemployment to prostitution, and became involved with the workers when she also lived in a working-class neighbourhood (Bentley, 2017). This deeply impacted her works, which became driven by material and psychological struggle themes. Here, when the mother mourns the loss of her child, it is not a loss caused by misfortune or coincidence, but that is deemed the fate of belonging to a working-class family. The old broken furniture in the room along with the walls that constrict the room perhaps alludes to the living conditions of the individuals. The concept of poverty is not just material, but also psychological- the individuals are poor not just in a tangible sense but also because they underwent a grave loss.

Grief is seen as essentially human, “It touches us all and is shared by all” (Moorjani, 1986, p. 1110). This humanizing quality of Kollwitz’s works makes them relatable and powerful in times of crisis. Whether through portraying her pain, empathizing with maternal figures, as well as highlighting the struggles of those who are suppressed, Kollwitz weaves multiple layers of sorrow into one through “Need”. Through symbolism, the use of the medium, and personification, she successfully creates a distinct voice of depicting grief, even within a movement that is specifically characterized by this very notion.

References:

Bentley, Christine. (2017). Maternity and The Self: A Social Construct in the Images of Käthe Kollwitz. International Journal of Arts and Humanities, 1(10), 908-938.

http://journal-ijah.org/uploads/ijah_01__67.pdf

Crawford, J., Melion, W. S., & Ramakers, B. A. M. (2017). Review of Personification: Embodying Meaning and Emotion. Intersections: Interdisciplinary Studies in Early Modern Culture 41. Renaissance Quarterly, 70(3), 1052–1054. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26560491

Gombrich, E. H. (Ernst Hans), 1909-2001. (1978). The Story of Art. Oxford: Phaidon.

Hammerstein, K., Kosta, B. & Shoults, J. (2018). Women Writing War: From German Colonialism through World War I. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110572001

Moorjani, A. (1986). Käthe Kollwitz on Sacrifice, Mourning, and Reparation: An Essay in Psychoaesthetics. MLN, 101(5), 1110–1134. https://doi.org/10.2307/2905713

Prelinger, Elizabeth. (1992). “Kollwitz reconsidered” in “Käthe Kollwitz”. [Exhibition Catalogue]. National Gallery of Art, Washington Yale University Press. 7-192. ISBN 0300057296.

https://www.nga.gov/content/dam/ngaweb/research/publications/pdfs/Käthe-kollwitz.pdf

Turner J. (1996). The Dictionary of Art. Grove, 34.

Woman with Dead Child, Kn 81 – Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln. (n.d.). Woman With Dead Child, Kn 81 – Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln. https://www.kollwitz.de/en/woman-with-dead-child-kn-81.aspx.

***

Tanisha Lamichhane is an undergraduate student of Liberal Arts and Humanities at O.P. Jindal Global University. Her research interests lie in art, feminism and resistance. She can be reached at lamichhanetanisha2001@gmail.com