In this series, we are trying to examine our personal and professional engagement with the popular, particularly the Hindi film. Some of us socialized as modernists and academics cultivate intolerance, scepticism and suspicion for the popular. For others, the popular has been an expressive, heterogeneous arena – fertile with political and poetic analysis. We use feminist and queer methodologies as well as the tension between the two perspectives mentioned before, to remember and reflect upon our journeys of affect, for the Hindi film and Shahrukh Khan.

Fanship for us, we suggest, is a placeholder for the personal and the political. It contains myriad productive contradictions and ambivalences. In analysing the film Pathaan, we look at key themes of identity, nationalism, masculinity, love and hope. We suggest that the film offers an opportunity to combine new and old ways of experiencing these ideas.

***

Sayantan and Bishal use the reparative method to do a ‘queer reading of an unqueer text’. In doing so they suggest that the spy universe of Pathaan is built around a relationality that is not given but made. The lack, or loss, of the familial that is present in the film resonates with queer lives. The search for a home, and a nation, that abandons queer people is a search that also unites them to build different spaces. Pushpesh, using the lateral method, ‘wanders’ across time and space in his exposition of the film. He traverses into narratives of other films like Badhai Do to argue that gay masculinity is neither neat nor homogenous, especially when it is constituted with the hyper-masculinity required by state forces like RAW and the police. As feminists, Deepa, Swati, Sneha, Rukmini and Gita deploy the standpoint of cishet feminists who claim their love, reluctant (Sneha) and ageing (Gita) for the popular, the Hindi film and SRK. We claim it for personal, pedagogical and political reasons. For some of us writers “coming out” as fans, as feminist fans, queers us in interesting ways. Given our academic trajectories and how we have forsaken, bent and undisciplined our canonical disciplines, we are already academic queers, outliers of sorts within academia. We find that our fanship is a further act of transgression, personal and professional. It spills over and also gets contained within measures of our own intersectional feminist practices. For others, an analysis rooted in fan-ship generates a critical intimacy – or perhaps intimate criticality. Media scholars, Paromita (as an artist) and Bindhu (as an academic), provide the larger methodological framework for looking at popular films, particularly Hindi films. Drawing upon their own practice, they argue that the popular lies beyond the binaries of realism and fantasy. Paromita’s use of Vasantsena’s lynchpin, suggests how it is important to think of stories, and not facts, as our entry point into Hindi films in general, and Pathaan in particular. Self-referentiality is crucial to this method and requires an understanding of the internal logic and code of popular cinema, deeply embedded in the civilisational and colonial languages of contemporary India. All of us writing for this series agree that the Hindi film cannot be fitted into straitjackets. It is always ambivalent and carries multiple contradictions. We would like to reiterate that each of us is an academic, and pedagogue, in particular domains and is writing here in an unconventional academic voice. We bring our (un) disciplinary locations and our epistemological standpoints to bear upon our engagements with the popular Hindi film, SRK, and the film Pathaan. As feminists, and allies, our essays are informed by contemporary feminist approaches on three axes: a) women and patriarchies are constituted at the intersections of class, caste, religion and other marginalities along with gender b) gender and sex are not constituted in biological and cultural binaries but are fluid inhabitations c) masculinity is also a construct that needs to be critically examined, interrogated and reimagined.

You will not find uniformity in our essays; these are accounts of subjectivity. Yet, the act of writing these essays, and listening to each other, as practitioners and academics, has started giving us a sense of togetherness, and solidarity. We hope there will be more joining in.

***

Cultural hypernationalism is exclusionary. It is especially so in current times. As women, we find the trope of the feminised nation and motherland has both falsely exalted and oppressively subjugated us. Feminist scholarship on how this narrative is steeped in patriarchal structures is well established. Queer critiques of such nationalism have pointed out how the feminisation of a nation is set in heteronormative ideals leading to the exclusion and abjection of gender non-conforming people, identities and worlds. Within this context, how do we view nationalism in and of Pathaan? Our series submits that we cannot see the nationalism in Pathaan as a hyper-nationalist, or jingoistic. We need a different register of analyses. First, given that Indian Muslims are continuously being tested for their nationalism in increasingly violent ways, finding a language to express it is becoming a challenge. Pathaan, like SRKs persona, is constantly navigating that challenge from the margins of Muslim identity, we see many of our students in classrooms having to do the same. Unlike the nationalism of those in dominant and hegemonic positions, the nationalism of those at the margins must be received differently is what we submit. Second, our essays work with the idea of home as central to the sentiment of patriotism. We position the home and its lessness over the idea of the nation. We suggest that it is the sense of exile and un- belongingness that is driving the language of nationalism in Pathaan. Third, we also submit that in drawing upon the possibility of the unitariness of a ‘good Muslim identity across the sub-continent, an identity that serves the world rather than nations, the film goes beyond national boundaries while rooting in the idea of home-nation, the watan. Perhaps in this imagination, we find hope.

Our series draws on another mindscape: that of love. First, each of the essays is inspired by the idea of romantic love that can be liberating while being relational, the idea of care so intrinsic to the SRK persona. We all speak of romantic love in our essays but also of love which may go beyond the romantic. Sailing this idea, we find ourselves speaking of desire, friendship, respect, kindness, community, patriotism, playfulness, of agape- ness as the basis of all love. These are things we unfailingly find in SRK’s persona, a persona constructed and consumed by fans and stars simultaneously. In the last segment of the panel discussion that accompanies this note, we choose our favourite scenes of love and romance from SRK films, it was an exercise in choosing magic, everyday magic, and fantastical magic. Connected to this is the second idea of love-based politics that has been central to the explorations of some, while others gravitated towards it more in the last decade, particularly during the anti-CAA movement. We see in the success of Pathaan, a moment of complex political articulation. The success of the film, for many, is symbolic of a fantastic love that might signal a new imagination of the secular, the plural, and the emancipatory in Hindi films. Of course, the emotional language of our imaginations is naturally and organically fractured. Just as our hope is.

– Editorial Note

Series Editor: Gita Chadha

(Like in any good collaboration, the words in this note belong to all of us)

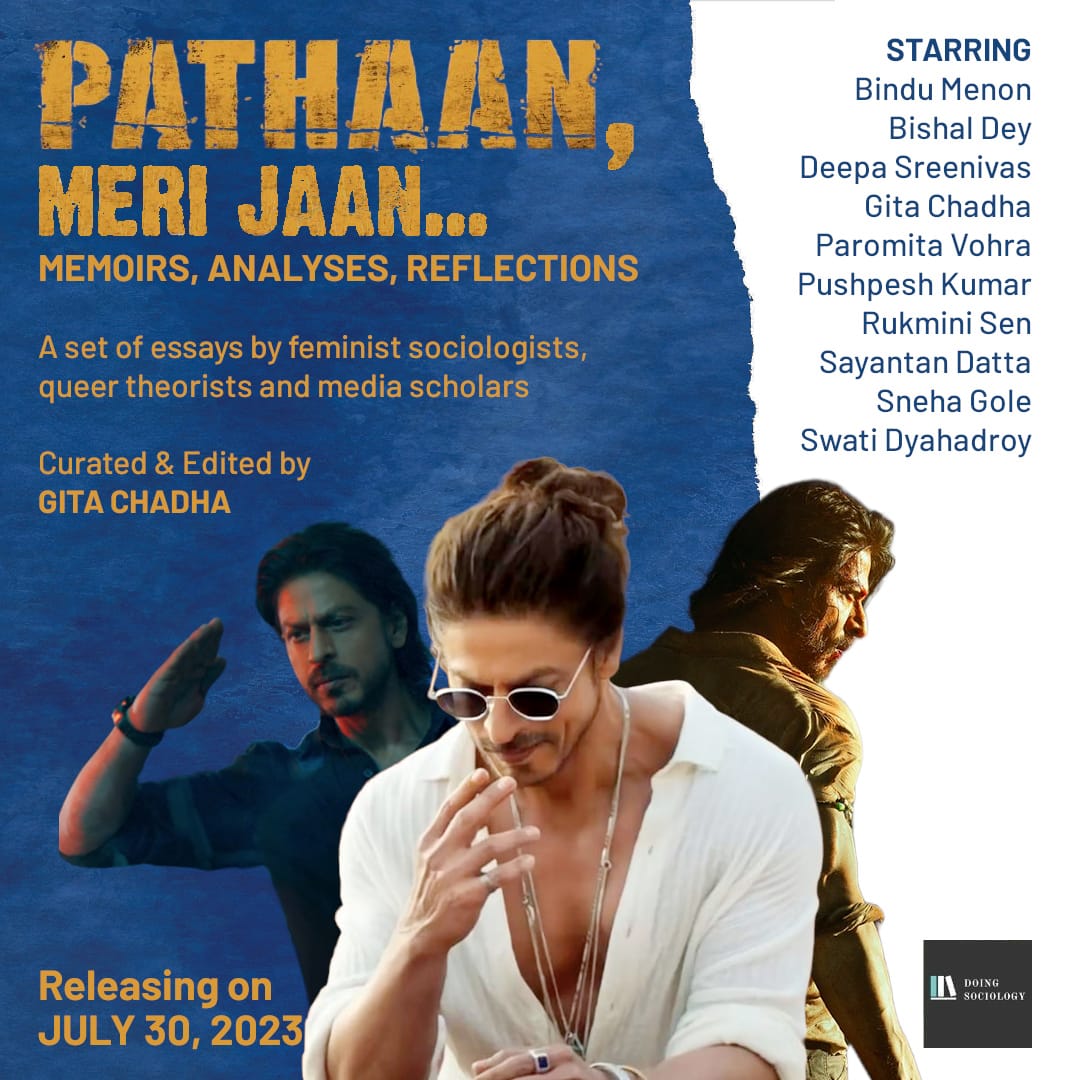

[…] essay is the latest addition to our Pathaan, Meri Jaan…Memoirs, Analyses and Reflections series curated by Gita Chadha. We thank Sayantan Datta and Sneha Gole for reviewing the essay and […]