Link to the editorial note and the panel discussion can be found here.

- KYA TUM MUSALMAN HO?: KAL/YESTERDAY (OR, WHICH FILM DID YOU REMEMBER?)

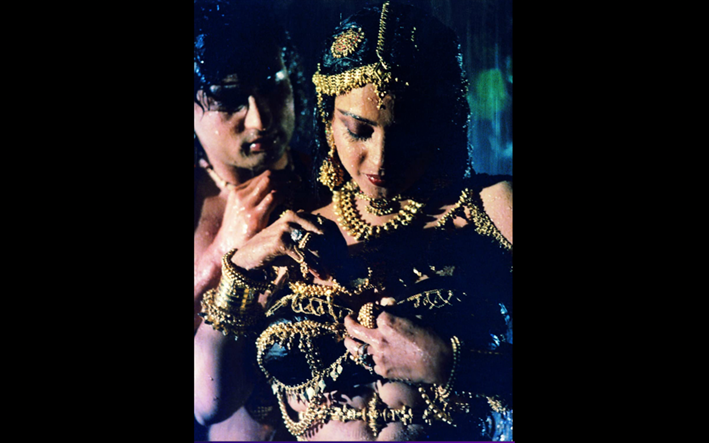

In the film Utsav (dir. Girish Karnad, 1984), when a young man, Charudutta (Shekhar Suman) and the famed courtesan Vasantasena (Rekha) first make love, she is clad in an elaborate ornament. Gold chains festoon her entire body and she asks him to undo them, unwrap her so to speak. The process takes a tantalizingly long time and ends with them both tangled up together, limbs and chains. Then next time they meet, Vasantasena sports the same chain ornament. Charudutt is dismayed – this again? She laughs and says, this time it will not take so long to undo. Reaching between her breasts she pulls out a pin and the entire assemblage of chains falls away, leaving only skin. The earlier elaborate undoing had been a sensual ruse, a seductive introduction of bodies. Now, they may slide softly into the place, where memory holds the key to lovers’ intimacies.

A scene in the film Pathaan functions much like Vasantasena’s lynchpin. It takes place in a Russian hotel. Rubai (Deepika Padukone), a Pakistani spy, wearing a spikily beautiful black bra over pants offers up her body to Pathaan (Shahrukh Khan) to be wrapped in bandages. Seduction is implied, but ironically. As Pathaan circles her body, with the bandage Rubai muses, “Pathaan… so that makes you Muslim?”

He answers not with a clarification of identity, but with a life story. It’s hard to say who he is, he replies. He was abandoned at birth in a cinema hall, from where he went to an orphanage, then remand home (juvenile centre). “You could say I was raised by the nation” and so, as a good son who serves his parents, he joined the army. Combat in an unclear war takes him to Afghanistan where he is injured. An Afghan family rescues and nurses him back to wellness. Before he leaves, in a familiar familial South Asian gesture, his caretaker, an older woman, wraps a taveez (talisman) around his arm to keep him safe. “You are our Pathaan” she says, a moonh-bola son. They are now (chosen) family that he visits every Eid, he finishes.

Like Vasantasena’s lynchpin, this scene opens up the film; it reveals, teasingly, the concerns that pulsate through the film but do not determine its rather nominal plot and invites the audience into an intimate embrace of film histories. Pathaan ki mehman nawazi if you will.

Somewhere at the back of our minds, on hearing this very ‘filmi’ narrative, we might also think of the question, which Rubai asks next. “What was the film playing in the cinema hall when this cinema baby was abandoned?” Pathaan never answers that question either. We might idly wonder about it – and each come up with a different answer to this game question, depending on who we are.

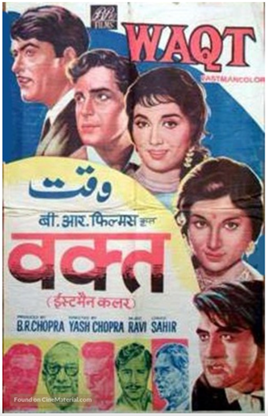

For instance, my answer to myself was Waqt (Yash Chopra, 1965), the film about a family of three children born on the same day, separated by an earthquake and a period – or the times—(hence Waqt), and about the journey of an orphan back to his family. Waqt itself recalled the first such Hindi film of a man separated at birth from his family and reunited through circumstance—Kismat (Gyan Mukherjee, 1943). Both films are steeped in questions of nationhood. Kismat, famously, for its song Door hato ae duniya walon Hindustan hamara hai ostensibly a slogan of support by the British subject for the Second World War, but heavily coded as a song about Indian Independence. Waqt, as a metaphor for Partition and its separations, both personal and cultural, and the nostalgic idea of a lost time of togetherness. Waqt was also Yash Chopra’s first film as a director, with which he broke away from his brother B.R. Chopra’s company paving the way for Yashraj Films, which has produced Pathaan. For another viewer, it might open up a different set of subliminal associations. In this way, different audiences can join their memories of cinema/cinematic memories to the scene, however unconsciously.

Rubai also then asks, “How did you go from being Lawaris to Khuda Gawah?” recapping the career of Amitabh Bachchan, the dominant star figure of a pre-liberalisation India, before Shahrukh Khan synced with its post-liberalisation psyche. The life-story Pathaan gives, as the collective consciousness of viewers knows, mirrors Bacchan’s most iconic roles where he traverses orphanages and remand homes, channelling the pain of emotional deprivation, migration and working-class masculine angst, in a set of defining films about togetherness, as well as the wounding separations (of class, of corruption) that undermine the dream of a new Indian nation.

In a press conference following the film’s box office success, Shahrukh Khan evoked the parallel to an iconic film about these social harmonies, Amar Akbar Anthony. He paralleled Deepika to Amar, himself to Akbar and John Abraham to Anthony. This is also the type of film termed a multi-starrer – one that has several protagonists each with their intersecting journeys, each played by a different star, with their iconography, not a singular hero, with his triumphal hero’s journey. In summoning these memories, Pathaan connects itself to an older popular cinema and cinema-going culture. It suggests that it is not Pathaan but all of Hindi cinema that is one heterogenous, mythic text, perhaps even all of the popular culture, its parts to be read in relation to each other. Bollywood too is after all an orphan child of culture, which has served the nation in different ways.

Pathaan is ostensibly a film about saving the nation – but as its end scene confirms—it is also a film about saving Bollywood. Here two superstars of post-liberalisation India wonder if it’s time to call it a day after 30 years on the job. They run through a mental list of potentials to carry forward the legacy. They name none but imply many, for us to fill in the blanks again. In the end, they resolve that these potential candidates don’t have what it takes. The responsibility must fall to them because, after all, it is a “desh ka sawal” – the question of the nation. It is mysterious to no Hindi film viewer that they are talking about themselves as stars, not spies. This intimacy, of saying one thing while meaning another, can be established only within a long-running relationship, with the audience as fans, as lovers of the star and of this cinema, who have their own code, who have a shared memory, which is being invoked repeatedly in and through Pathaan.

The Kya Tum Musalman Ho scene also echoes other, more recent memories. In refusing to respond to a question of identity with data and responding to it with a story of habitation, kinship, love, chosen families and moonh bole rishte instead; that is, answering a question about Muslim identity with a story about belonging and connection, the scene is an echo of the slogan Hum Kagaz Nahin Dikhayenge, drawn from Varun Grover’s poem. The slogan bound the protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, which made religion a basis for citizenship, and required Muslims especially to provide elaborate documentation to prove they are Indian. It recalls the polyglot celebratory politics of Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh sit-in which performed, as a protest, a theatre of belonging to a way of being Indian, with its shared food, acerbic older women, poetry, whimsy, emotional politics and also, occasionally, political contradictions.

The scene offers up the film as a potent aggregator of heterogeneous memories. Pathaan prompts a memory of another Bollywood cinema, one Mukul Kesavan has described as an Islamicate cinema with Urdu roots, made up of many cultural elements invalidated under colonialism, scattered with the passing of patronage and excluded from definitions of culture and respectability under the once-new nation too; a cinema that metaphorically made room in the dark for many who were not considered to be creatures of light. Many single-screen cinemas were reopened because of Pathaan – a fact emphatically broadcast by Shah Rukh Khan on his social media, invoking this part of the Hindi film.

In recalling an earlier version of Bollywood film, it calls up not only the memories of cinema, but the kind of memories cinema helps preserve, of emotion, experience, and identities of those who are erased by narratives of respectability and even law–outlawed tawaif and devadasi cultures, invisibilised queernesses, lost rhythms of homes in other regions, migrants and the dispossessed, elopers, interlopers and adventurers—people who are not only citizens, but also denizens, of a nation/land; memories of being, that are never easily contained in a single or singular notion of the nation, or for that matter politics.

Pathaan encourages us to recall these more imperfect but heterogeneous spaces and to remind us, the audience, that we are a part of this memory and it is a part of us, even as we inhabit a time of crushing homogenization. It does so in a sidelong, implicit way, without any declared ideals (perhaps because those overt claims are no longer viable in ongoing public discourse) or as an explicit topic. In that sense, it too is a cinema that performs a Hum Kagaz Nahin Dikhayenge theatre of belonging, not of borders and boundaries (although we may argue that borders are nevertheless invoked, with the mention of Kashmir, even if they are a source of strife, and the film is not staged on those borderlands).

Amnesia and mnemonics play pivotal roles in the plots of many older Hindi films (“main kaun hoon? main kahan hoon?” – “who am I? where am I?”—being the recurring dialogues of such scenes we often joked about). Sometimes memories are stored away because the present holds no place for those emotions. In post-colonial, post-Partition cinema, fate or history– and the two are so intertwined in Hindi films – take memory away almost as a test of belief, connection or love. In that time the amnesiac deluded, or lost, inhabits another self. The question is will they recall their earlier self? Only we the audience hold their memory for them, willing it to return.

Memory returns to the amnesiac in shards and fragments, and sometimes these fragments join together in a rush. Upon the glimpse of a taveez or gesture, the phrase of a song or a melancholic dancing ballerina in a music box, the lost past is reclaimed into the present.

But even if there is closure, what has transpired in the time of dis-connection infuses the resolution. We must accept there is no seamless return, but one refracted through what has happened in the time of absence from one memory, inside another.

Perhaps Pathaan is a reverse moment, a mnemonic inviting the audience to rejoin shards of memory in danger of fading away, to remind it of its optional self when we live in a time of violent sundering and insistent polarisation. It is tempting, for the secular liberal to think of these only as the shards of a communally fragmented nation, but perhaps this act of remembering is not so limited or politically instrumental and is connected, rather, to an intersection of divisions. Perhaps to remember, what is dis-membered through the fragmenting narratives of contemporary times: legalistic political languages judging behaviour and utterance for political purity, binary political positions that are converted into full identities, even on dating apps, narratives of carefully categorized marketing, atomized social media selves and stories, and of course narratives of a majoritarian, monolithic state whose past is being swiftly rewritten. To re-member is to grasp a more fluid, porous, relational identity of self and of Indianness, one capable of flowing through the testing time of today, from the kal of yesterday to the kal of tomorrow.

2. KINTSUGI AND REMEMBERING: AAJ/TODAY (OR, LOVE CAN NOT CONQUER ALL)

Pathaan begins, not with the hero’s entry, but with the introduction of a mysterious antagonist, a man with a tattoo that says “Patriot”. This antagonist is not a minor one and presents an existential challenge.

Bollywood – like some other Indian cinemas—has always played with the audience’s knowledge and experience of what is off-screen, inviting them to infuse it with what is on-screen, especially through the figure of the star. It is a cinema aware that it is co-created in the viewing. So, it is made with that elasticity of theatre, to accommodate the interaction of a diverse audience, whose responses might also influence each other, building a web of affective relationships in the moment—the creation of a momentary public through sensory means. Few stars have enabled this as much as Shahrukh Khan, whose films are full of self-referential intertextual play with a wink to the audience. More so in the time of Instagram, where fans continuously reiterate this persona through interview excerpts and remixed images—the Instagram reel is a song of devotion extolling the qualities of the idol. Pathaan’s character is infused with fans’ knowledge of Khan’s own life: orphaned young and forging kinship and connection with fans and friends.

Early in the film, there is a laboured scene about Kintsugi, the Japanese art of joining broken pottery with gold, focalizing the break not as a flaw, but as beauty, a healing, that preserves the memory of the break. It is a self-consciously metaphorical scene, as Pathaan first speaks about his body being reassembled with plates and pins and later talks about his disbanded department as scattered shards to be reassembled into a new department, JOCR–a gang made up of tukde tukde if you will. For some audiences, this operates as a metaphor for the fractured polity of the nation. For others it is a reference to the body of Shah Rukh Khan which has undergone its surgeries – but also its surveillance in US security check X-rays, beeping at his Muslim surname, not his metal.

All of these metaphors are operating. But as Pathaan is also a conversation about and with Bollywood, this is also a metaphor for Shah Rukh Khan’s on-screen persona, fragments of which are re-assembled to create the persona of Pathaan. These are present as visual echoes. Pathaan upside down in a crashed car where the enemy almost, but then does not shoot him, recalls a near-identical scene in Dilawale (Rohit Shetty, 2015). Pathaan, hiding behind and being saved by Rubai as goons give chase recalls a similar scene in Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi (Aditya Chopra, 2008). And of course, breaking into a woman’s home to steal a key and singing Tu Hai Meri Karen is a joke referencing Khan’s role in Darr (Yash Chopra, 1993) as a stuttering stalker, and the song Tu Hai Meri Kiran.

Shahrukh’s persona, in various films, tends to explore the idea of the divided self. In Baazigar (Abbas-Mastan, 1993), as a wounded outsider, he wishes to kill the person he loves. In Duplicate (Mahesh Bhatt,1998) he reprises the classic Bollywood trope of the double role (in fact he has played a double role in 8 films) as a god-fearing chef and a calculating gangster. In other films, the idea of the double person is present in one character. In Rab Ne Bana di Jodi (Aditya Chopra, 2008), he masquerades as a cooler version of himself to woo his wife, creating confusion about whom/which she loves. In Dilwale (2015) he re-creates a new identity to erase the hurts of the past. In Jab Tak Hai Jaan, his past and present selves are divided until they become unified by a phase of amnesia. In the course of the films, the divided selves come into an accepting, fluid whole-ness.

His characters also engage with the divided self in others, especially women. Most notably in Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge (Aditya Chopra, 1995), the character of Simran (Kajol) helps the woman, who is usually forced to choose between father and lover, denying one or other part of herself, in love stories of social opposition, to have the love of both. He compels the uncompromising patriarchal figure to abandon this notion of who a masculine patriarch is and soften. In Chennai Express (Rohit Shetty, 2013) he does the same with Meenamma’s (Deepika Padukone) controlling father, who has sent his henchmen to bring back his runaway daughter. Khan’s character does so in a scene where he questions the value of Independence Day and an independent nation in which a woman’s feelings (not only rights) cannot be understood and where she cannot choose a life of her liking. He addresses this question to the unyielding patriarch and says only one thing can loosen the grip of this hierarchical thinking: love (this scene can be found on YouTube with the title Because I Love Her). Powerfully and quite unusually, in Jab Tak Hai Jaan (Yash Chopra, 2012) and Jab Harry Met Sejal (Imtiaz Ali, 2017) he exhorts the women he loves to join their own divided spirit – between propriety and sexual-ness—to freely inhabit the spectrum of their womanhood and is a companion as they undertake this personal journey, not only a journey via a relationship with Khan’s character.

In all these films, as he seeks to join what is divided in others through gestures of love, desire and understanding, certain healing also takes place for the characters Khan plays and they can salve their loneliness, their splitting of love and sex (Jab Harry Met Sejal, Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi), or mature into relationality with others which are not centred only on their egos.

But Pathaan is different – a puzzle for this very persona of love which reigned over peacetime, and aided our emotional transition through the dream of a globalized India whose dark side is today, unmistakably around us.

In Pathaan, the emotional cleavage, the divide is present in Jim.

Abraham is an antagonist to Khan’s protagonist because his strongest characteristic is not the traditional villain’s lust for domination. His essential rasa is cynicism. He has been betrayed by a country to which he gave allegiance, and now he feels he owes no one any allegiance. Such figures—such as Sunny Deol in Damini (Raj Kumar Santoshi, 1993) are usually anti-heroes. When they experience this bitterness, they are often brought back into a space of idealism through a fight for justice. In Damini, this is through a woman who questions the oppressive caste and patriarchal power structures which have also outcasted these embittered masculine characters (caste is the unspoken word, but the operative quality of the rapists and their accomplices in Damini).

Jim’s identity like Pathaan’s, is uncertain. Jim could be short for James or Jaimini or Jamal for all we know (someone we might encounter in Bandra’s Bazaar Road). The only marking he has is the tattoos, one of which is ‘Patriot.’ His adherence to patriotism is binary. It is all or nothing. But it has a context.

Jim’s backstory is recounted by Pathaan’s boss Luthra (Ashutosh Rana). Jim was once a star Indian spy. When his family is kidnapped by Somali pirates, the department refuses to pay the ransom, and his pregnant wife is killed. Betrayed by the nation, Jim becomes a mercenary of sorts. Luthra describes him in opposition to Pathaan: he was excellent at his work, “calculative, methodical”, not like Pathaan who listens not to his superiors, but to his “dil ki awaaz.”

In keeping with that characterization, Pathaan’s first response to the story is a criticism of the State he serves. Disparagingly he asks, “Why couldn’t the country pay the ransom for someone who served it so well? The department has no shortage of funds. You would have done it for a Minister.” Luthra bristles. “Department monies are not for personal use.” Pathaan scoffs—what worth a notion of righteousness which has no place for love, no salve for wounds? “Your one decision has provided a righteous justification of his every gunah (a word that is sin, crime and fault at once) in his eyes.” Dimple Kapadia goes to fetch Pathaan after a long exile with the line, “Pathaan ka vanvas khatam hua.” It is a different evocation of the Ramayana. Maryada—doing things by the book, or kaagaz—can wound, and it can also refuse to acknowledge the wound. It is not that ‘villains’ do not have backstories of pain and othering in other films. But it is rarely that someone expresses empathy for their backstory, as Pathaan does here for Jim. And thereby acknowledge the flaws of the very idea they, as protagonists, represent.

Jim has converted his wound into amoral cynicism. When Luthra tries to invoke his past as an Indian solder he laughs coolly “I’m just an Indian businessman.” He owes no one anything (a very modern relationship indeed, suitable to the time of hypercapitalism). Alienation goes hand in hand with doing business. Jim is a kind of floating NRI. The film presents its definitions of love and cynicism, as typified by Pathaan and Jim. Love which is in some ways a personal covenant or belief is present with a critical intimacy. Pathaan can validate Jim’s anger while maintaining loyalty and is capable of collegiality even with the enemy (Rubai and Pathaan being friendly colleagues at one point). The politics of love is not limited to singular identities or allegiance. It is committed but not exclusive. Many forms of allegiance and kinship, personal and political can, almost should, co-exist as they do for Pathaan, making identity inherently non-binary, with blurry borders. On the other hand, cynicism is absolute and binary, whether in allegiance or disaffection.

In Dilawale (2015), Khan’s character suggests that the only way to move into the future is not to hold on to a single story of the past. As he reunites with his estranged lover, Kajol, he acknowledges their history of violence (their fathers killed each other and she has also shot Khan, thinking him responsible) with a joke. “Bade bade shehron mein asis chhoti chhoti cheezein hoti rehti hain, Senorita”, he says, quoting his dialogue from Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge, gesturing to not just the history of the characters in this particular film, but their past as co-stars and lovers in another film, and the audience’s relationship with all of these things. Love is the antidote to wounds and misunderstandings.

But what if there is no misunderstanding? What if a wound has never been validated, a schism never acknowledged? Since Jim’s wound was not acknowledged, he is in a realm outside these invocations of patriotism, nationality and love. Had Jim’s wound been acknowledged, there may have been another road, even a claim to be made on him. But Jim’s history, where a State did not acknowledge its unfairness and unkindness—cannot be forgotten by Jim. In the absence of acknowledgement, amnesia is not an option. Jim is not available for healing. Jim will hack the weaknesses of the state, its flaw points, with a virus whenever he can. This is a critique as much of where unquestioning patriotism leads, as of the State. But the State is the source of the wound. Shahrukh Khan’s politics of love meets a hard border here. What he defends is not always defensible. If one must remember, one must also remember the wound of the other.

Since reminiscence ripples through Pathaan, this is reminiscent of a quite different karmic narrative, and the figure of Kangana Ranaut. Ranaut, in an interview on Koffee with Karan, the very heart of A-list Bollywood, had pointed out the flaws of the Bollywood state, accusing it of nepotism, and rejection therefore of those seen as outsiders. The unwillingness of the Bollywood elite to acknowledge that wound, built into a huge war, that weaponised the suicide death of Sushant Singh Rajput in 2020. Ranaut entered this fray, along with other film figures like Vivek Agnihotri and Paresh Rawal, entangling the binary of Bollywood elites and outsiders with the political binaries of right-wing and secular. It threw the idea of Bollywood as a melting pot of outsider figures into question; a past that is not quite the description of its present. It is a narrative that mirrors the story of Jim. But it also mirrors how Khan himself eludes that narrative, which sought to draw him into its binaries during the arrest of his son Aryan Khan on drug charges in 2021. The ultimate outsider and also the ultimate insider can command a public that is not pre-categorised in subservience to the dominant political binary.

In the impasse embodied by Jim is a kind of acceptance that Shahrukh Khan/Pathaan’s algorithm of love, cannot conquer all, after all. That the nation wounds many and cannot expect to bring them into an embrace.

Since Pathaan is also in constant dialogue with Bollywood’s histories, past and future, the question of cynicism also extends to how films are made in a corporatized context, going with trends, “calculative, methodical”, not one that listens to its “dil”, where intuitive desires can have some play. If popular cinema has dispensed with larger-than-life gestures, with the catharsis and emotional acknowledgement of melodrama, where is the heart to go?

In a time of sanctioned political amnesia, where one must not allude to politics directly, where histories are being constantly rewritten and distorted, perhaps remembering the past, not forgetting it, is one way forward. And perhaps too, an acknowledgement of defeat is necessary. An acceptance of being broken down, and having to find a way to re-assemble the liberal self, its capacity to wound as much as be wounded, and which takes its goodness, its progressiveness, for granted.

3. MARD KO DARD HOTA HAI: KAL/TOMORROW (OR LET’S BE REALISTIC, BUT NOT WITH REALISM)

Conversations about the future of Bollywood have of late abounded in the public sphere, and have also been a constant refrain on the show Koffee With Karan. Koffee with Karan is the home of A-list Bollywood – the nepotism accused—and also the place where the critiques of nepotism were made by Kangana Ranaut. Hence the show, like the State, is the point of origin of disaffection). In its questions about its future, the world of the show, rooted in a Bollywood which rose post-nationalism (a (his)tory similarly recounted in The Romantics (2023), a kind of corporate documentary series about Yashraj Films) is full of anxieties about being decentred in a time of neo-nationalism. The host, Karan Johar, in its last season, lamented flagging Bollywood fortunes with endless self-flagellation of “what are we doing wrong?”. There were covetous comparisons to blockbuster films from the South, propelled by heightened masculinity and right-wing resonances, among other visceral qualities that audiences respond to.

The arrival of Pathaan, at first seemed to mirror this masculinity in superhero mode.

In one sense it cannot be denied that there is a far more masculine persona for Khan as an action hero, than before. At the same time, this masculinity is diffused in the scene I’ll call Mard ko Dard Hota Hai. Pathaan is being transported on a train to some Siberian prison (we think), and fellow spy Tiger (Salman Khan) makes his cameo appearance to rescue Pathaan. In the middle of the fight sequence, he offers him a Crocin, for the pain of having been beaten up. Pathaan dismisses it with the cliché “Mard ko dard nahin hota” (real men don’t feel pain), then winces. Tiger nods wryly and Pathaan accepts the painkiller. In the end, they split the strip of Crocin before going their way.

Shah Rukh’s persona has always provided an alternative masculinity –caring, vulnerable, companionable and most of all light-hearted and pleasurable. In Pathaan, he in fact infuses the kind of hard masculinity increasingly dominating the public sphere with some of the qualities of his earlier soft masculinity–though we might also say he fuses his earlier persona with this one, putting some of this hard masculinity into it. Throughout the film, this masculine figure – the ripped action hero—does not undercut itself, but it does not insist on masculinity being taken too seriously. As before, the character goes with the instinct of trust and collegiality – such as with Rubai. He gets played, and nurses some resentment, but no enmity is forever and his relationship with her goes on to be one of friendship-love, and concern once they have made up. Mard ko dard hota hai but it need not, as masculinity in Hindi films traditionally has done, fester into a vendetta. He takes some painkillers rather than make his wound the reason for not believing and so, never healing.

This is in continuity with Khan’s essential persona – one where he both, plays the “good” nationalist Muslim but also refuses to erase his Muslim identity, where he acknowledges tradition and authority but does not quite submit to either. While some see this as a compromise (an all-or-nothing binary), it also offers the idea of a third domain of the political. Politics is a way of being, a collection of beliefs for interpretation, not a labelled position, aka hum kagaza nahin dikhayenge.

This heterogeneity is manifested through Khan’s playful persona (as exhibited in the mard ko dard hota hai scene), which, on-screen and off, maintains sincerity without earnestness, through an invitation to have fun, to fool around, to play—and through this play to connect deeply. It is a play, that also refuses realism with its implication of singular reality and ‘real truths’ for a world of multiple, even contradictory, truths and the possibility of change.

For many, the absurd plot of Pathaan is a point of criticism. Realism, especially for the liberal left, has constantly been presented as a superior aesthetics (closer to truth) and by extension a superior politics. Its linearity has been praised in contrast to the digressive modes of Hindi cinema and the ornamental aspects of song and dialogue. But, realism, as aesthetic, is as much about political fantasies (nowhere clearer than on television news as fantastical films are about reality). The social amnesia of the present—as much in how a part of the public un-sees violence and political silencing while another avoids accepting waning liberal influence—is bolstered by a constant rewriting of actuality in terms of realism. Consider the rise of films like The Kashmir Files and The Kerala Story, titled like forensic dossiers on the ‘truth’ of communities and histories, mimicking a similar realism-garbed, evidence-giving filmmaking used by liberal filmmakers, whether in documentary or parallel cinema, to speak of social reality. The aesthetic of realism offers a coherent view of reality, which is often considered superior, but eventually represents a schema with a fixed conclusion, quite like coherent masculinity.

Realism also positions itself as more serious, more ‘issue-based’ and this sobriety is equated with being rational and intellectual. The libidinal excesses of Bollywood and its fandom then, become defined as base and purposeless, therefore politically wasteful. The liberal fan, newly converted to SRK love, now willing to claim Shahrukh because of this concentric of political meanings, continues to affirm this idea of political fidelity – to love the one who serves ideology.

But, this is a cinema which resists coherence, channelling a deliberately in-coherent form like older forms of Hindi cinema, outside the linear narrativizing of the Hollywood studio Hindi film. Being full of contradictions, detours, innuendo and emotional saturation, it contains a dynamic, shape-shifting possibility, which has always allowed social anxieties to be managed, alongside space for social change to be galvanized.

The most compelling quality of Pathaan then, is its very vagueness, its faux realism of a piece with the non-realism of Hindi cinema, and of bahurupiyas, which play with fact and fiction to evoke sensory truths. Their fuzzy borders open them up to multiple interpretations – much like the nation. But we must acknowledge that while all these interpretations have their context, none of them will ever feel complete, each will enact exclusions and make wounds and so, none can be fixed forever. Rather there must be a continuous re-interpretation and re-engagement with these narratives from diverse perspectives for this enterprise to be meaningful.

Pathaan’s vagueness, this very thin relationship to actuality is not a-historical as much as a defence of memory over history as a way of making meanings about reality – and in that sense a deeper, less document-ary kind of historical. What is the memory of Indianness we are losing? How can we remember it and take it with us into a future that is less fractured?

Between social amnesia, and holding on hard to fixed histories, the act of remembering offers a different frame, a less determined frame, one that acknowledges the possibility of versions of the truth. Jim’s version of India and Pathaan’s version of India are equally true – for both of them. Between amnesia, and holding on hard to the past, the act of remembering proposes a different more emotional journey.

The most powerful element of the on-screen off-screen interplay in Pathaan is the recent history of Shahrukh’s persecution by the government through the incarceration of his son on flimsy drug charges, imagined as a next chapter in the narrative of nepotistic, liberal Bollywood, by the right-wing. The remarkable occurrence was the surge of love that this called up in the public, evoking a memory of an earlier context, where all emotion was not in service of political ideologies and an Indianness Khan has always represented, rooted in practices of apnapan and mehman nawazi. The idea of a popular figure not subsumed by either left or right but one with a direct relationship to the love of a heterogenous following is a song and a suggestion, of spaces of meaning-making and selves that are not controlled so centrally, or defined so fixedly. Watching Pathaan becomes an act of remembering this state of being. It is without a doubt that the resounding success of Pathaan is rooted as much in this most recent past as the far older pasts of Bollywood histories which echo experiential histories.

- YANIKI: AAGE HI NAHIN PEECHHE BHI

It is an unprovable argument, so I offer it as a reading. On a second viewing after a long gap, Pathaan does not quite have the same purchase. The emotional saturation usually found in a Hindi film, especially a Shahrukh Khan film, is missing here, which renders the film a little arid. That reveals the nature of its structure, porous and suggestive in such a way that we surge forward to fill its empty spaces with our meanings, our surging inner world of desires – which for a long time had no place to go in the cinema except the visceral masculinities and jingoistic halls of Kashmir Files and Kerala Files.

In that sense, Pathaan operates more ephemerally, in quite the same way as a pandal, where the godhead aggregates meanings and metaphors of the times, audiences worship, eat, dance, and submit themselves to sensual steeping in the unsaid meanings where past and present merge and join and are then washed way to make way for a new period and way of being.

Pathaan cannot be seen in realist and instrumental terms as being aligned with a left-liberal agenda except to serve an ego-centric fantasy. Pathaan evades these politically correct and therefore politically subservient readings. It is a borderless political event, not a political document. It has no fixed end in mind, but that does not make it aimless. It desires to make a hit film and while doing so to re-assemble the idea of the Indian self in more accommodative terms, to provide a conversation about nationalism that steps out of the designated binaries of left and right and their linear, realist continuities and also allow a participation in a nationalism that is not based on othering and opposition. It also suggests a politics that is more episodic that allows newness to constantly enter rigid discussions.

We can see it then, as one episode in an episodic political story—linked but not necessarily coherent and singular—which also includes the anti-CAA protests, the farmer’s protests, the wrestler’s protests and the Bharat Jodo Yatra. An expressive idea of politics rooted in the imagination of existence, rather than a realism-based politics of election. That the two influence each other is a given. But that the two need not be identical, is a necessity.

Through the inclusive frames of kinship and love, fun and pleasure, and evoking archetypal figures rather than realistic figures, this cinema ultimately seeks to empower the viewer in some completely different way, inviting them into the realm of experiential knowledge and the right to interpret ideas, including the idea of citizenship and nation as much as gender and sexuality.

It is this that makes Pathaan eventually a response to or even an assertion of what the popular can be, beyond the populist. It’s an invitation to play, joke, and have fun, in an endless round of interpretations, a constant churning empowers the audience to once again make its meanings, to join its meanings to the object on the screen, to function as a powerful memory aggregator.

In some ways it is not only a memory box but a memory capsule, collecting with it many different memories of being that we will need not only to forge a new future but to inhabit it. When the times allow us to emerge from amnesia into a more forgiving chapter, we will need to remember what it means to live in and sustain such a world. Shahrukh Khan has presided over India’s big change from pre-liberalisation to a globalized economy and culture. He has offered a politics of love, but also of markets, kinships and pleasure. It is not radical politics, but it is full of radical possibilities. For many years now, his films have not succeeded for a variety of reasons – a weakened self-belief in both him and the public, a need in the public for an aggressive nationalism. We can certainly read in the success of Pathaan another possibility, another desire, a longing for another self which we are currently divided from.

***

Paromita Vohra is a filmmaker, writer and committed antakshari player. She is also the founder and creative director of Agents of Ishq, a platform about sex, love and desire, for Indians.

[…] Vasantasena’s Lychpin, Memory Games and Re-Membering in Pathaan: A Reading in Three Scenes – Par… July 30, 2023 […]