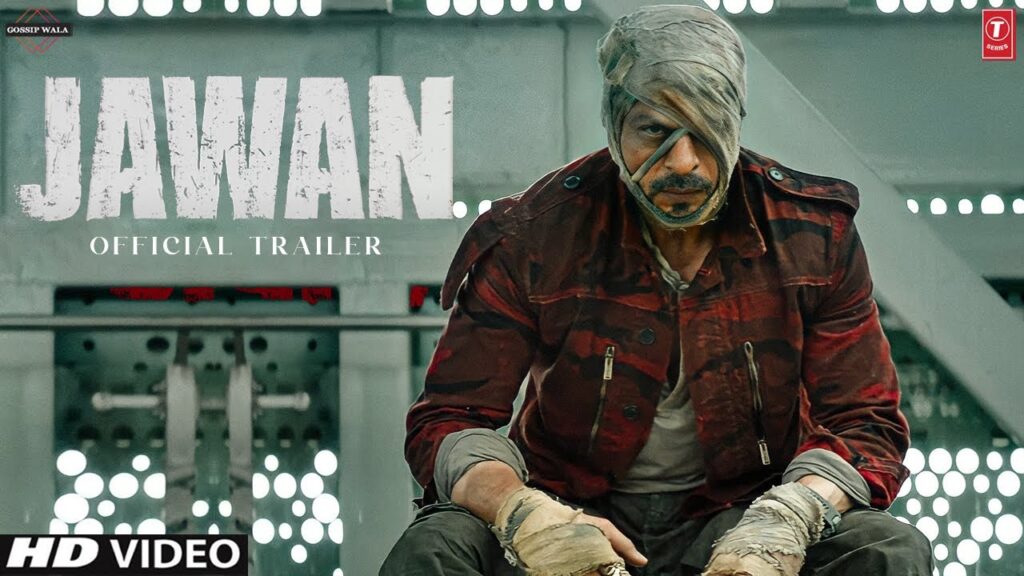

Shah Rukh Khan’s yet another blockbuster (Jawaan) on ‘mass hero image’ runs in theatres as I write. Much has been written on Shah Rukh Khan. This piece is however not based on its visual imagery or modes of representation, but an attempt to look at what happens beyond screens – in the form of celebrity worship and celebrity culture in India. The release of the movie witnessed fans pouring milk on SRK’s poster, and cinephiles wrapping themselves in bandages to go to the theatres. Indeed, this act of dressing up for the movies (say, the latest Barbie sensation) or pouring milk (palabhishekam) on gigantic cut-outs (of Akshay Kumar to Jr NTR) has become widely extensive and everyday-like in the twenty-first century. What does this worshipping of their favourite heroes or heroines in movies tell us about cinema and its spectatorship? How do we analyse this sociologically? Using these as entry-level questions, the paper attempts to set out the meaning of celebrity, celebrity worship and popular culture in a nation where stars may very well be labelled as gods.

Daniel Boorstin’s definition (1962) one of the most cited and celebrated ones refers to celebrity as ‘individuals, well known for their well-knownness’ (p.67). Among the various categories of classification of celebrities, of particular interest to us is the category of the ‘star’ (Monaco, 1978; Rojek,2001) referring to those who find success and recognition by talents; playing himself or herself in music or acting. Celebrity culture, as we know it today, has largely been a development of the 20th century (Cashmore, 2006 ), with the latter half of the 1900s witnessing the emergence of worshipping fans, from Micheal Jackson wannabes to the reverential MGR. The almost divine visual and aural signs that circulate around movie stars are owing to the ubiquitous nature of cinema in India, often quoted as the ‘poor man’s entertainment’ (as cited in Dickey,2007). What Durkheim lays out in his Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912/2008) makes this veneration comprehensible.

Though Durkheim’s theory on totem and totemism dealt with primitive societies, we see celebrity worship as a social reality in the times we live. The sacred/profane distinction, if one may use this to emphasise the boundary between the mundane and extraordinary, is stark here; the worlds of the celebrity are far from the commoner’s imagination. They lead extravagant lifestyles, host fancy weddings and go on lavish trips (Alexander, 2010). The fans treat the posters of their stars with actions that imitate temple rituals, hence bestowing the sacred/deistic status. The worshipping of the star therefore is not merely a celebration of stardom or cinema, it reflects the revealing dichotomies of the sacred and profane in the sociology of everyday life. The ordinary crave to get a glimpse of their favourite stars, and the sacrality of celebrity stars is secured and maintained, away from the masses. The greeting of fans from their bungalows ( Jalsa or Mannat) for either Amitabh Bachan or Shah Rukh Khan is often cited as a ‘ritual’, indicating a certain disassociation from the mundane. Many actors and actresses have temples dedicated to them in India (Rajnikanth, Samantha etc.). In the city of Chennai, citizen’s ‘holiday ritual’ is about taking Darshan at the renowned actor MGR’s samadhi (Jacob,2009).

The characters heroes play, or the roles they assume in mass narratives further shape the forms and meanings attached to celebrity worship. For Alexander (2010), the fictitious characters, seen as extra-territorial, lead to the production of creative imaginations and aesthetic forms among the masses. Words fell short for the foreign friend I met at a restaurant to talk of ‘Pushpa’ and Allu Arjun’s style. On general class train journeys to Agra and parts of Rajasthan over the last year, I was party to numerous conversations on admiration and adoration for Pushpa and Rocky Bhai among young lower-class men; with sometimes entire coaches humming the songs. At one level such characters and narratives mark the appreciation of a stylistic form- of the deviant, dangerous hero, on the other it thickens the status of the stars and offers to celebrity worship. This takes us to the final section of the essay, are fans or worshippers of celebrities then mere recipients or uncritical consumers of popular culture?

Largely psychological assessments see the celebrity worshipper as either an obsessive loner or hysterical (Brooks, 2021). Beyond this, an examination of cinema as popular culture, its acceptance by all social classes, and in particular promulgation largely by the lower classes (Dickey,2007), encourages us to look at fandom in multiple ways. The culture industry of Adorno and Horkheimer (1991) may look at how the practices and activities of fans are structured and manipulated. On the other hand, fandom is also conceptualised as empowering; with worship fans wielding the power to influence and configure the realities of their hero (Chaturvedi et al.,2020). Though the level of this influence may be contested, it would be too simplistic to account for worship fans as being just mindless or consumed in fantasies. In the celebrity culture we live in, aren’t we all fans of varying degrees, indulging in our ways of worship? Indeed, cinema as popular culture is one of the most powerful institutions of today and looking at the creation of celebrity culture, the idea of celebrity as a totemic figure and the role of worship fans gives us meaningful ways to understand the nature of celebrity worship in India.

References:

Adorno, T. W. (1991). The Culture Industry: Selected Essays on Mass Culture. Routledge.

Alexander, J. C. (2010). The Celebrity-Icon. Cultural Sociology, 4(3), 323-336.

Boorstin, D. J. (1962). The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-events in America. Atheneum.

Brooks, S. K. (2021). FANatics: Systematic Literature Review of Factors Associated with Celebrity Worship, and Suggested Directions for Future Research. Current Psychology, 40, 864-886. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9978-4

Cashmore, E. (2006). Celebrity/culture. Routledge.

Chaturvedi, R., Singh, H., & Singh, A. (Eds.). (2020). Hero and Hero-worship: Fandom in Modern India. Vernon Press.

Dickey, S. (2007). Cinema and the Urban Poor in South India. Cambridge University Press.

Durkheim, É. (2008). The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (J. W. Swain, Trans.). Dover Publications.

Jacob, P. (2009). Celluloid Deities: The Visual Culture of Cinema and Politics in South India. Lexington Books.

Monaco, J. (1978). Celebrity: The Media as Image Makers. Doubleday.

Rojek, C. (Ed.). (2010). Celebrity. Routledge.

***

Amratha Lekshmi A J is a PhD research scholar at the Centre for the Study of Social Systems (CSSS) at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi.

[…] figure, projecting onto it their shared values and even libidinal energies (unconscious desires) (The Fundamentals of Celebrity Worship – Amratha Lekshmi A J – Doing Sociology). In modern secular society, celebrities arguably fulfill a similar totemic role. They are […]