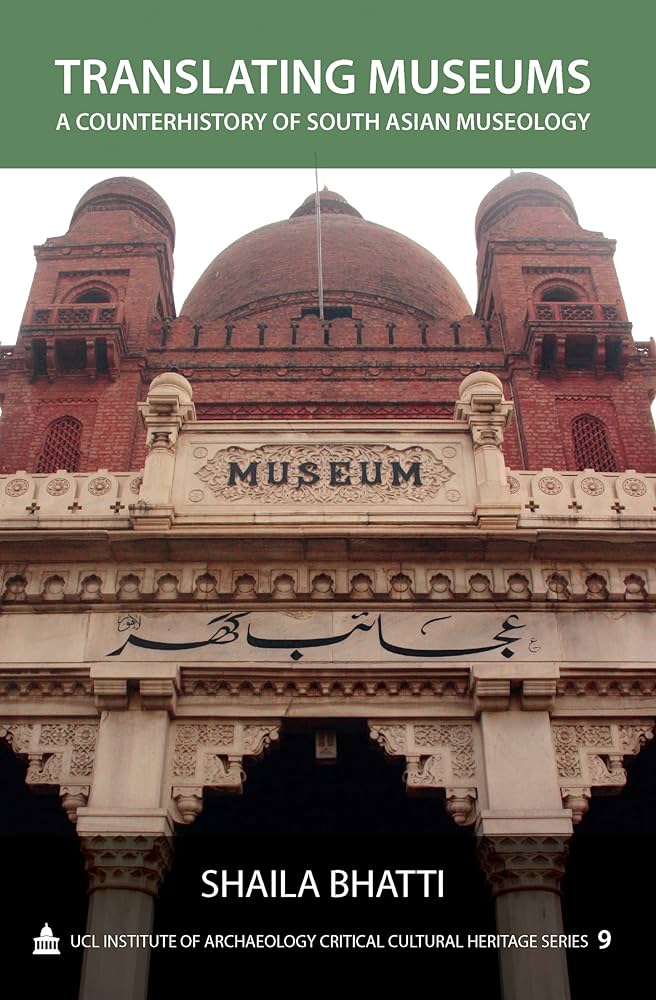

Shaila Bhatti’s Translating Museums: A Counterhistory of South Asian Museuology, published in 2012 by Routledge, traces the formation of Lahore Museum in 1856 under the exigencies of colonial rule, to the changes brought about by partition/decolonisation and the subsequent remaking of it in postcolonial Pakistan by considering how visitors respond to the museum. Her emphasis on counterhistory is to show that museums in South Asia need to be studied in their histories and circumstances that differ from how museums work in the Western world. Bhatti analyses this difference through the arrangement of collections, the institutional praxis of the museum, and how visitors interpret the museum and its collections.

Chapter 1 highlights the formation of the Lahore Museum in the mid-nineteenth century as part of an emerging grid of institutions in British India that sought to map and utilise the trade and commercial potential of the region. It further charts the histories of the 1864 international exhibition, the appointment of John Lockwood Kipling as the museum curator and head of the art school in 1875, and the role of government surveys and donations by the British and native elites that led to the enhancement of the museum’s collections. According to Bhatti, the wide-ranging collections of the Lahore Museum relating to art, history, archaeology, ethnography, and science gave it the veneer of a universal survey museum (although without the totalising trope of Western museums). In the first half of the twentieth century, the museum’s changing role entailed educating the public by arranging collections through neat ordering, labelling, and cataloguing its exhibits. Although this period saw the inclusion of Indian elites in the management of Lahore Museum (for instance, the appointment of the first Indian curator in 1928) and an increased emphasis on the museum as an institution of knowledge and social progress, the chapter also explains the limits of the museum’s pedagogical role as an imperial archive.

Chapter 2 focuses on the Lahore Museum’s transformation into a postcolonial institution in the wake of decolonisation, which involved partitioning India and making a new state of Pakistan. Although the chapter indicates the disastrous impact of partition, which led to the division of museum collections (40 % of Lahore Museum’s collections were transferred to the Government Museum in Chandigarh), it does not get into the details of what was transferred and how this was achieved indicating the possibility of new research. The partition led to the museum’s closure for the safety of its collections, and it finally opened following the 1965 renovations. In the latter half of the chapter, Bhatti demonstrates the expansion of the museum from a mere seven galleries during the partition to the addition of new galleries in the later years (Islamic Gallery, Independence Movement Gallery, Sadequain’s calligraphy, and the Manuscripts and Calligraphy Gallery) that sought to create a nationalist identity influenced by Islamic histories. Bhatti, in this chapter, shows that this postcolonial transformation in the museum did not lead to the alteration of existing galleries which included collections of objects (relating to Hindu/Buddhist/Sikh histories) from colonial times. Therefore, the postcolonial transformation in the Lahore Museum did not come as a radical break from its colonial past. Bhatti sees in this process a possible vision of a Pakistani nation that is a moderate Islamic state accepting of its cultural heterogeneity. However, her analysis of the museum does not touch upon the competing regional/ethnic groups (a political history which she recounts in the introduction of this chapter) and if they complicated the museum’s construction of a moderate Islamic identity for Pakistan.

Chapter 3 analyses the habitus of the Lahore Museum and considers some of the challenges that arise in the everyday life of the museum because of the national and global cultural policy enacted by the ministry in Pakistan and bodies such as ICOM (International Council of Museums). Bhatti points out the need for a more robust cultural policy at the national level and the need for training programs for museum staff. She also shows that programs led by international bodies like ICOM rarely consider local needs and demands. Although the museum undertakes pedagogical initiatives such as lectures and quizzes, they merely serve the purpose of tokenism. Drawing on interviews with museum staff, Bhatti suggests that in the wake of a lack of resources and networks, though the museum staff remain aware of the lack in their institutions, they project the poor functioning of the museum on the illiteracy of the visitors. In doing so, they create the museum as a place of authority.

Chapter 4 brings visitors’ agendas to the museum, showing that visitors are not mute observers. Instead, they employ their agency and creativity in interpreting the cultural institution of the museum and its collections relevant to their needs. The chapter highlights the embodied and visceral responses of the visitors that are less about the archaeological chronology or the cultural value of the collections/objects and more about their feelings taking form through interpretations and allegories. The elements of curiosity, wonder and resonance remain the identifying features in how visitors respond to the Lahore Museum. While Bhatti does not want to present the visitors’ response to the museum through any fixed statistical formulation or a fixed lens, she, at the same time, seems concerned that for visitors, the Lahore Museum is not a significant part of their identity. As she writes, ‘a contestation or broadening of the nationalist vision is possible at the Lahore Museum, since it has kept safe evidence of the pluralistic history, culture, and civilisations that make up Pakistan’s past- Buddhist culture of the northeast, the Indus Valley, Hindu Civilisations, and Sikh Kingdom- a religious and cultural diversity that is missing in other accounts of identity. However, unclear narratives, an obsession with protecting masterpieces for the Gallery In-Charges, and neglect of visitors prevent the museum from being part of, or alleviating problematics concerning, society’s contemporary identity, culture, and heritage.’

Chapter 5 considers the dialogical interaction between the visitors and the museum by drawing on conceptual histories of darshan, nazar and interlocular. The chapter stresses the need to understand the visitors’ engagement within the museum through a polyscopic vision that derives as much from cinema, television as novels and local fairs.

The book, therefore, highlights the search for an ‘indigenous’ understanding of museums in South Asia through a rigorous engagement with visitors. A more elaborate and critical engagement with the museum’s collecting histories and objects would have unpacked the social and cultural valence of the museum better. Nonetheless, the book is significant for combining historical and ethnographic methods to present an understanding of the museum informed by both the past and present. It remains the only published monograph on museums in South Asia, suggesting more research is needed.

***

Akash Bharadwaj is a PhD researcher in the Department of History and Archaeology at Shiv Nadar University (SNU), Dadri, Uttar Pradesh.

[…] post Translating Museums: A Counterhistory of South Asian Museology by Shaila Bhatti (2012): A Review by … appeared first on Doing […]