Source: Scroll.in

Introduction

COVID-19 cases have retreated but the fetters of the virus continue to impact us. It brought about a terrible hit in the field of performing arts and artists in particular. The art that was once for the ‘being and becoming’ of many became restrictive and exclusive with the rise of virtual media that was bereft of any physical aura of touch or listening.

Art has always remained a major means for the survival of many. Perhaps art is a means of survival not just for the artists in this regard but also for innumerable others who share and enjoy the art. This can range from a bird sitting on the branch of a tree and attending a concert to a dispossessed labourer lying beside a pond and listening to the very same concert. It can even be a tree swinging and dancing with its branches, as a reaction towards its enjoyment of being a part of the concert. Art is hence something that transcends boundaries no matter what. Today this boundary has been transcended through a mechanical reproduction that comes in the form of technological equipment and other accessibilities. While there is no scope to question the indomitable spirit these equipment have brought about into the field of art in terms of improved access during the pandemic, it also needs to be understood and remembered at the same time that, there exist innumerable others like the earlier said birds, trees and the dispossessed labourers who also seek resort in art. And who at the same time do not have access to the same.

This brings one to the major point of considering art as not a commodity to be consumed, but rather something that is to be experienced without any designated means. A better way of putting it would be – art is to see and hear and subsequently become whatever one wants to become. It is not a binding tool that designates one to sit in a hall or the comforts of one’s house and then achieve pleasure. My grand-uncle used to listen to the late Sri. M. D. Ramanathan the acclaimed Carnatic musician on his radio, with a cigarette in his hand bending forward, resting his belly onto the desk, standing and thinking nothing, but of course deeply immersed in his world and space-time. That was his personal space which he created and enjoyed being in. Perhaps somebody else would prefer to listen to Sri. M. D. Ramanathan in some other way. Hence the duty of the performer and the listener is to go beyond any fixated boundaries, be it both in terms of time and space because art as earlier said cannot be contained into a ‘this and that’ space and time, rather it transcends boundaries. It is just that art forms vary through art as a being continues to create ripples of fantasies and scintillating experiences. Having said this, today in these trying times how far technology has come as a redeemer and at the same time a swallower of our earlier interests is what is attempted to be looked into further.

Art and It’s Way of Seeing – Pre and Post Pandemic

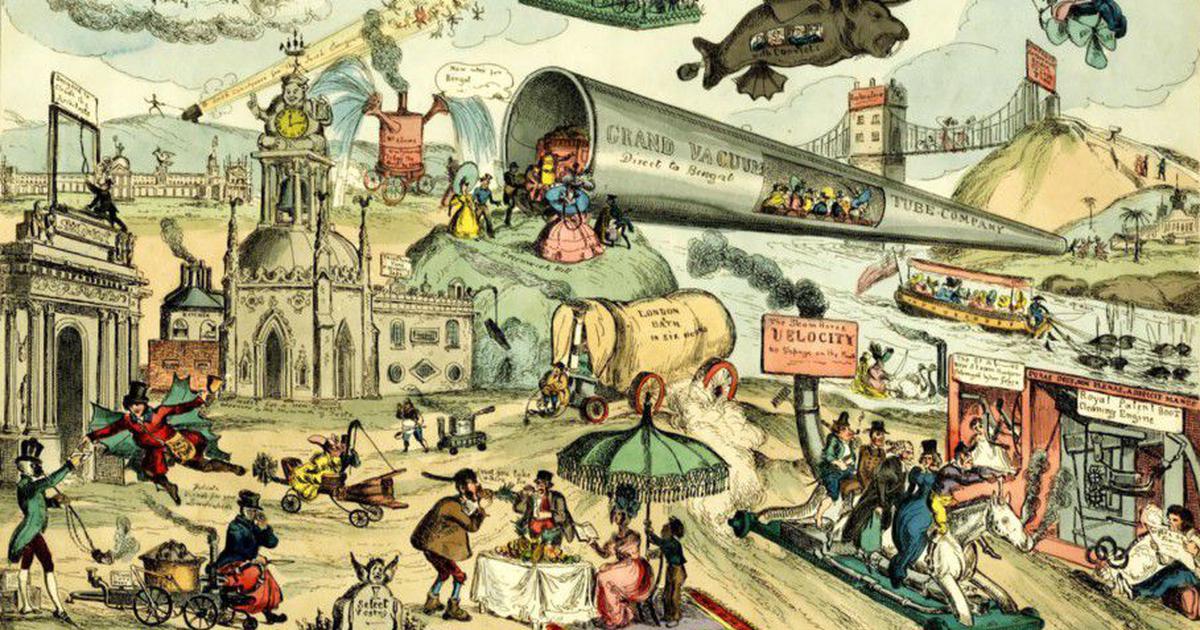

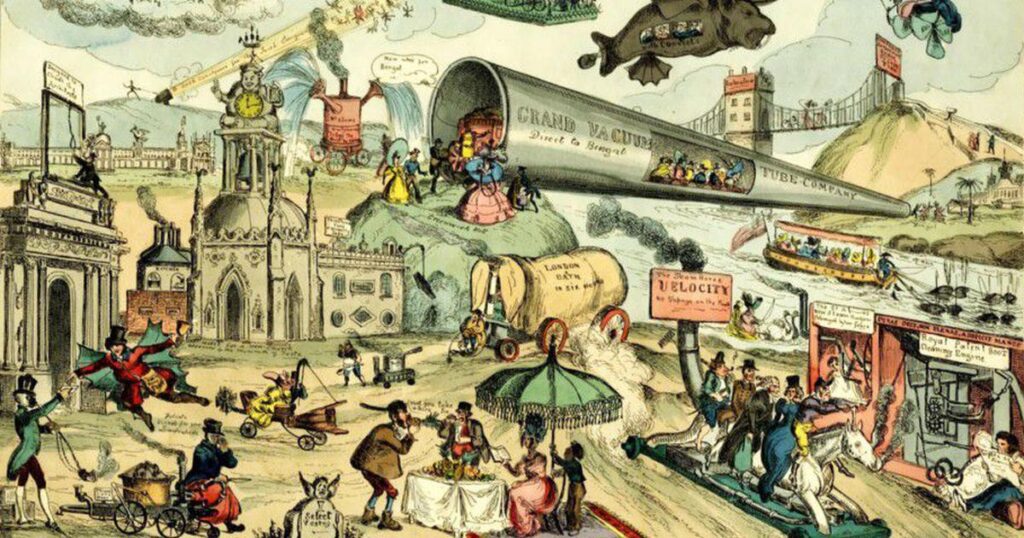

Though a post-pandemic shift in art is an immanent tendency capitalism is emerging as an encroacher into the social status of art. Such a development needs to be also positioned in the long drawn processes beginning with the coming of the camera and the moving images. If one may route back into identifying the “origin” which can be understood in Walter Benjamin’s philosophical sense, as “that which emerges out of the process of becoming and disappearing”, capitalism as an economic disorder in such a regard cannot be kept as a stand-alone. This is because the very disappearance in itself is something deeply engrained in the very evolution of capitalist reproductions. In other words, with new mediums of reproductions, the old starts disappearing, just like how pen drives are no longer required to transfer movies because friends say it is available on Youtube, Netflix, Prime etc.

Also, an interesting look back into the 1990s video and media practises in India shows issues of identity, critiques of violence, narrative and performance, and other subjects that come under the umbrella of third-world issues as deeply political, social and democratic. In this 21st century however an ‘epistemic departure’ can be very well foreseen if not already. Thanks to the overpowering impact of the new age technological reproducibility have gripped the urban credo. They successfully use aesthetics as a major means to mould out a thought of the new disorder. An underpinning of such a kind results in the breaking asunder of human and social nature. They cease to be mutual guarantees (Ranciere, 2009).

Studies point out that from 1990–2005, new media remained a closed activity, accessible only in a few Indian viewing spaces and galleries (Sinha, 2005). However, such a past needs to be positioned all the more consciously in the present because an ‘epistemic departure’ becomes evident at this point of an intersection where there is an immanent capitalist transition of an art or media reproducibility from being in a ‘social physical space’ to disappearing into a ‘virtual enclosed space’.

Navjot Altaf (b 1949) in the large installation links Destroyed and Rediscovered (1994) (can be viewed using this link – https://www.navjotaltaf.com/links-new-1994.php ) using large coiled and severed cables and excerpts of documentaries of the series of bomb blasts and subsequent riots in Bombay. His installation recalls the violent aftermath of the demolition of the mosque, Babri Masjid, in Ayodhya. In the mixed-media installation Carrier (1996), Vivan Sundaram uses the metaphor of an upside-down boat with a video recording of the classical singer Shubha Mudgal performing works by Kabir( 15th cent.), a symbol of religious syncretism in the subcontinent (Sinha, 2005). Therefore at a time when such performances and installations gripped the world and its larger consciousness and motivated people to see a world anew, the recent new-age technological reproducibility fail right there. This is so because consciousness in itself has become a time-bound, highly restrictive reproduction bereft of any political consciousness. And driven by commercial imperatives. Technology and art in a pandemic world continue to remain anti-democratic even today, even as the world is slowly heading towards a post-pandemic era.

Technology and Art in a Pandemic World

Many artists are dispossessed from their art as well as their living because of the pandemic. Spaces have started becoming large and constrained at the same time because of the pandemic. Large in terms of technology, constrained in terms of access. While the dominating spirit of technology as a means of using survival benefits needs to be appreciated in this time of a pandemic, it also needs to be remembered that art is not always something that must rest alone in technology.

No monetary value can render pleasure as much as art can through its reproduction. Today though technology has come as a redeemer to confront this reality, the primary economic problem that is attempted to be raised here is that not all can afford to be listeners of any art for a monetary value. This tendency naturally side-lines the once public nature of art now reduced to a commodity available for only a few who could afford to pay. Hence art is not always to be seen from the eyes of the artist for his or her sole sustenance rather it also needs to be seen through the eyes that see and experience the artists. After all the artists achieve their social aura only when art becomes available for all, without any limits to its access. It is also in this light the appreciable effort of taking Carnatic music outside the boundaries of sabhas needs to be seen as a movement to break the established Brahminical well-entrenched orders.

Stuart Ewen explains the creation of mass consumer culture as being part of an ongoing development of social control well abetted through a system of what he calls ‘corporate survival’ (Ewen, 1976). The recent technological reproductions appear to be such social controls that have withdrawn the basic logic of what art was once earlier. We all are enthusiasts of art forms and anybody reading this article by now would’ve mostly attended some concert or performance by somebody or the other in a real physical space, before the pandemic knocked on everybody’s doors. Attending a concert in a physical space became probable because of the pandemic and technology offered temporary relief. But tomorrow if this temporary relief becomes permanent, it would be the erasure and the dispossession of a series of artists and the innumerable others who would be completely alienated from their once earlier enjoyed public physical spaces.

Artists in capitalist transactions become objects for a bunch of people/organisations to reap profits. This naturally results in the art performed by these artists being transformed into a mere tool for valorisation. The central tendency of capitalism hence rests in valorising an art to its improbable extent by assigning a monetary value for its surplus generation. The public characteristic of art before the pandemic was never of the above kind. It is hence in this regard, strikingly enough it has to be accepted that capitalism as a rule has been effective in encroaching into the everyday life of performing arts, artists and its enthusiasts. This occurs through creating a belief in the person that he/she is enjoying everything like the way it used to be, pre-pandemic sitting in their enclosed shelters and comforts.

The only change experienced becomes the platform which is nothing but a light-emanating screen. This light-emanating screen has also been successful in evoking a sensation in most of its procurers; a deep sense of satisfaction with whatever they have procured via the online performance by paying an assigned monetary value as ‘the best among all possibilities’. The translation of the assigned monetary value embedded in a performance that is reproduced through a technological medium for a seemingly public credo is where the ‘epistemic departure’ of art in contemporary physical spaces sprouts. Behind this transaction begins a very seemingly natural process wherein, like in any other transaction, a person pays money and gets to see the art form he/she wants on the screen. In this transaction begins the ‘epistemic departure’ of art primarily because art was never an object of an assigned monetary value. Secondly, capitalism as a well-entrenched system has been successful in encroaching into the everyday lives of the people (artists, nature, dispossessed labourers, etc.) by emanating a deep sense of feeling that nobody is a victim to this predatory system and things that have shifted to the light emanating screen stands equally ‘artsy’. In other words, capitalism has been systematically effective in confirming to the mob by and large, as well also to its artists, with a deep sense of satisfied feeling, through creating a virtual aura of their performative success.

Capitalism has used art as a level playing ground which constantly creates a discourse of creating ‘the other’. ‘The other’ refers to the public credo that does not have the capital to access any art that is sold for a monetary value. As I noted at the start ‘the other’ in this context can be the birds, trees, dispossessed city dwellers, marginalised workers etc. who experience and love art for their well-being and not for any monetary value. Sadly it is this dispossession that has been the immanent tendency in any capitalist system.

A post-pandemic world might face a squeeze and stress in terms of coming back to an earlier enjoyed physical space that art as a being once enjoyed, pre-pandemic. Therefore, it is in this time of handwringing when capital encroachments are at their all-time high and technological reproducibility pervades the larger interest of a public space where art earlier used to be performed, the task to the world by Walter Benjamin seems to be all the more telling. The task henceforth is the ‘grasping hold of a memory in the moment of a danger’.

Jagadhodharana

During the peak of the pandemic, a man with his tremendously applaudable skill on his Nadaswaram unearthed a brilliant rendition of Jagadhodharana which means Jagadh- the world and uddharana the one who saves the world or rather gets the world into the right path. He was a performer who gained his survival through his renditions and he might continue to be so though the doors were locked down during the pandemic. But as we all are aware, art is what the artists are made up of and no doors can shut their art, for when one door is closed hopefully another door opens. Perhaps that’s how art used to function earlier too. But in contemporary terms, we have arrived at a stage where not all may have access to the doors of technological reproducibility which has largely pervaded the public consciousness of art. Such a fact needs to be confronted on an urgent basis primarily because not all would prefer a space of technology as reproducibility for showcasing their art. Over and above that neither is technological means of reproducibility a ‘democratic space’. Dispossessed informal workers after a tiring day may have access to a public physical performance of an artist, but these very dispossessed informal workers may not have the necessary means of technological reproducibility to enjoy the same performance in a virtual space. Not only is this an issue of class conflict but this is a larger issue of access as well as preferences in a democratic sense.

Man said Aristotle is political because he possesses speech and a capacity to place the just and unjust in common, whereas all the animal has is a voice to signal pleasure and pain. Therefore the question in point is who possesses speech and who merely possesses voice? The refusal to consider certain categories of people as political beings has proceeded by a refusal to hear the words exiting their mouths as discourse (Ranciere, 2009). A particular video that has gone viral comes as a signifier in these trying times of a telling reality which many artists have become victims of. This was a video that has gone viral, but the due effects of this technological virality are nowhere heard. A major understanding from this video of the art performed by this Nagaswaram artist[i] with a cow by his side is that “music lingers even with or without listeners”! Art moves on but the performers may not always!

References:

Benjamin, W. (1935). The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction in Illuminations edited by Hannah Arendt, translated by Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books, (1969).

Buck-Morss, S. (1989). The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. The MIT Press.

Rancière, J. (2009). Aesthetics and its Discontents. Polity.

Sinha, Gayatri. (2005). New Media Art in India. Grove Art Online.

[i] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kxSw-ZeAdXU

***

Sankar Varma is a Research Scholar in the Department of Economics, Christ University.