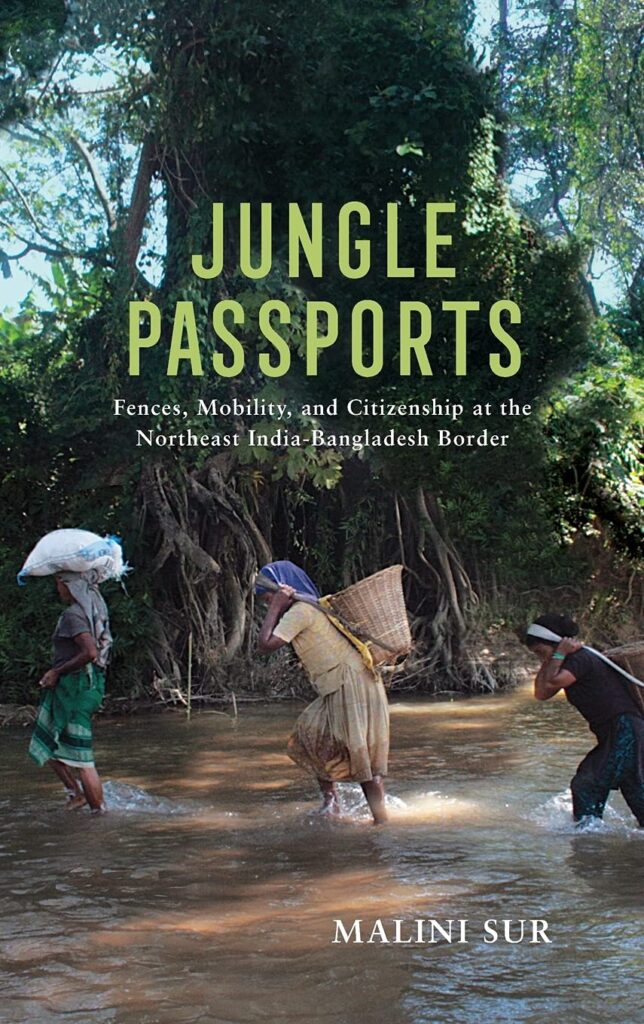

‘Jongol Passport’ (p. 17) a borderland expression combining both Bangla and Garo words, delve into the post-colonial issues of one of the highly ‘militarised’ and ‘socially produced’ borders of the Indian sub-continent (Paasi, 2022). Jungle Passports: Fences, Mobility, and Citizenship at the Northeast India-Bangladesh Border by Malini Sur (published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in 2021) is an extensive ethnographic study conducted between 2007 -2015. Sur argues that borders and fences are unfinished projects of the states. In this case, an unfinished postcolonial cartography. She portrays the north-eastern India-Bangladesh border not as a story of mere ‘barbed-wire fences’ and ‘imagined borders’ but as an ‘assembly of life forces’ (p. 8). She sees the borderi, another borderland lexicon (p. 12) as areas of relationality, sustenance, uncertainty, cooperation, legality, illegality, exchange and dependency. Throughout the book, she aims to explain four key elements such as ecologies, infrastructures, exchanges and, mobilities and states that these four elements shape the force of life and loss at the conflict-laden India-Bangladesh border. Her ethnographic work combined with rich archival study describes the daily lives of borderi communities living with both ‘visible’ and ‘invisible’ fears. Jongol is one of the elements of daily lives that allow Garo women across the two countries to facilitate the trade of ‘reject clothes’ (p. 93) through forests (Jongol meaning forest). Sur demonstrates that the jongol and the ‘border’ are the lifeline for the local communities across the fences as well as serve as a brutal divide between the two countries.

She begins with an introduction to Roumari-Tura Road, connecting Roumari, a sub-district of Kumirgram in Bangladesh with Tura in Meghalaya, India. Kumirgram is one of the flood-affected borderland districts of Bangladesh where poverty remains the largest factor for human relocation and resettlement. In saying so, she also details how the road itself is a racialised postcolonial infrastructure built by Garos to advance resource extraction for the British. The road now cuts an international boundary, becoming sites of continuous mobility and surveillance including the racialisation of Garos. Later, she moves on to describe how ‘rice’ became militarized, controlled and policed and continues the legacy of early colonial territory making (p. 53). Abandoned fertile land and harvests were re-assigned to refugees ‘post-colony’, perceived as sharing communal identities and thus being more loyal to the state (Ahmed, 2006; Pegu, 2004). Rice thus is implicated in the acquisition of land, the racialisation of people, and their citizenship, and the securitisation of the border.

In the third chapter, she narrates how controlled territory-making facilitated a partnership between the border forces and borderi peasants, unpopularly called out as ‘Muslims’ and cow smugglers. She goes on to provide a rich account of the business of cow smuggling, of how it is a male-dominated sphere. She uses the term fang-fung, a term commonly used in chars[i] that denotes duplicity and dependency to indicate cow smuggling. Irrespective of border fear and risk, and border contentions among politicians, there exists an unsaid mutual ‘friendship’ and ‘cooperation’ among traders and politicians across the fences to facilitate cow smuggling. This shows how the border functions as a site of patronage and dependency, as well as fear where military, agriculture, trade and nature co-exist uneasily with each other.

In the subsequent chapters, she draws heavily on her ethnographic work in the char chaporis located in Kumirgram, Mymensingh and Netrokona in Bangladesh and Meghalaya and Assam in India. She continues to explain how the lives of cow smugglers remain tied up with the animals they trade-in. She highlights the cross-border kinship relations that help sustain the ‘trade’ amidst the local power struggles and borderi fear of loss of life. She highlights that there is a sense of shared space and moral entitlement towards the high and sharp barbed wire fences around the borderi.

Abruptly breaking out from the ‘jongol’, Sur draws the book to the court spaces and Foreigners’ Tribunals of Assam where she critically addresses how Muslims are termed as ‘cow smugglers’, non-citizens, and outsiders in Assam. She delves into how a heavily bureaucratic exercise violates basic human rights and democratic principles. She demonstrates how ‘racial’ discrimination continues against those who lack resources to negotiate with state mechanisms, and in this process, they are moved to the margins of being non-citizens. In a short afterword, she highlights that borders are fundamentally spaces of mobility through poverty, kinship, trade and so on

Overall, Sur’s detailed ethnography and minute insights on borderi life are a valuable addition to postcolonial literature and scholarship on northeast India-Bangladesh. This is not an easy task as the border is heavily militarised and the author herself reflects on the impacts of this at various points in the book. This shows that ‘the dust from old maps and new fences will never settle at borders” (p. 12).

References:

Ahmed, S. Z. (2006). Factors Leading to the Migration from East Bengal to Assam 1872-1971. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 66, 999–1015.

Paasi, A. (2022). Examining the Persistence of Bounded Spaces: Remarks on Regions, Territories, and the Practices of Bordering. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 104(1), 9–26.

Pegu, R. (2004). The Line System and the Birth of a Public Sphere in Assam: Immigrant, Alien, and Citizen. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 65, 586–596.

[i] Riverine islands. In this context, it is used for the islands of Brahmaputra, (Jamuna in Bangladesh).

***

Mamoon Bhuyan is a Doctoral Researcher in Sociology at Brunel University London.

[…] post Jungle Passports: Fences, Mobility, and Citizenship at the Northeast India-Bangladesh Border by Mali… appeared first on Doing […]