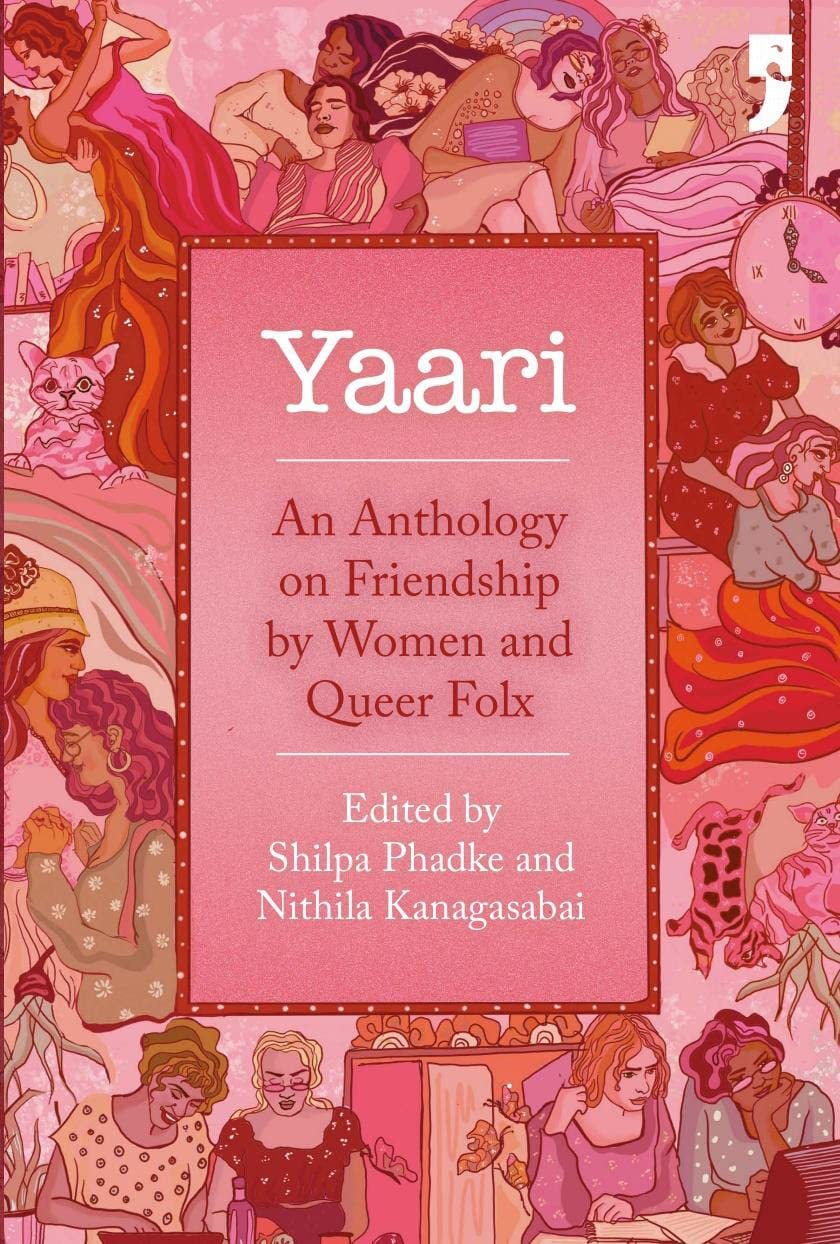

There are some books we read for pleasure. Some, we read to advance our knowledge of the world, others to feel seen and heard, and a few, to motivate us, to make us want to do things- like changing the world. Yaari, a 524-page Anthology on Friendship by Women and Queer Folx, edited by Shilpa Phadke and Nithila Kanagsabai (published by Yoda Press in 2023) is one of those rare gems that manages to achieve all these aims, rolled into one life-affirming piece of work that is much greater than the sum of its parts.

A review of academic texts usually follows a set script and tone, with sharp critique in jargonistic language often presented as constructive criticism. But Yaari is not a book that lends itself to such scrutiny, as it stubbornly refuses any force-fitted, neat categorisations, much like the friendships and their stories it highlights. From personal anecdotes to historical accounts, myths to poems, conversations to artwork, Yaari does not even choose a singular form as the only acceptable way to discuss friendships. Across nine beautifully themed sections, covering emotions which themselves often overlap, it presents the contributions of nearly a hundred academics from across the South Asian continent, detailing their experiences of, and thoughts on female friendship- by women and queer folx.

Freed from any expected conventions, the collection takes a life of its own- one which is very difficult to “review” against any expected standards. What Yaari reminded me of instead, was bell hook’s work, which taught us to not shy away from placing ourselves at the front and centre of our scholarship. Which is exactly what Yaari does. Encapsulating lives, as they are lived, detailing friendships as they are felt.

The unabashed centring of female and queer experiences in the book was so refreshingly powerful that it almost made me sad to remember what we miss out on by not giving a voice to women and other gender minorities more often and more prominently in academic work- I wondered what the world would look like if such scholarship was the norm, rather than the exception?

The central premise of the book also strikes at the heart of the patriarchal stronghold on relationships, in which romantic, heteronormative relationships are given a primacy rarely accorded to other relationships – especially friendships. Through detailed, moving accounts of friends as lovers, sisters, enemies, chosen families and perpetrators of the most heartbreaking betrayals, Yaari explores the place of friendships as a life force for women and queer folx as a uniquely gendered experience. Such an experience does not rest on an exclusion, instead, it focuses on the specific ways in which female friendships, or those between women and nonbinary persons are experienced within patriarchal cultures, in a way that male friendships are not.

Through its sections on Love, Intimacy, Friendship [S1], Girls, Women, M(others) [S2] and Grief, Longing, Loss [S5], the authors discuss the role that culture, especially Bollywood tropes and popular literature have played in devaluing such friendships, relegating them to the ambit of childhood or eliminating their need from the lives of married or partnered women. The sections shed light on the loss of friendships, their conspicuous absence in women’s lives, the lack of space to mourn them, and the gradual withering away of friendships by women too exhausted to keep up with the many roles they are already expected to juggle. This is contrasted with how such platonic friendships nourish us when they are allowed the space, time and care they need, and the (often delayed) realisation that women have, to not overlook their importance.

In the sections on Resistance, Solidarity and Solace [S3] and Distance, Disappointment and Rage [S6], the book asserts that friendship is a political act- “as a way to both practice and extend our politics” (P437). Covering themes from #MeToo to the CAA protests, mental health struggles to disability rights, and the shrinking space for minorities both religious and sexual in the context of growing majoritarianism in the subcontinent, it asks the important question of whether friendship can truly be divorced from allyship. Refraining from taking a political position, as the accounts in the book remind us again and again, is a privileged position, and silence, complicity. It is through repeated transgressions that “bonds of loyalty and belief” (P334) are tested, with friendships often becoming the price to pay for living authentically.

But friendships are also what sustains us- across borders, across time, across generations and against narrow caricatures that our positionalities can force upon us. Written during the height of the COVID pandemic, distance- both perceived and geographical, enforced and chosen, is a key theme running across the book. In the sections on Pandemic, Protest and Resilience [S5], Virtual Realities, Technologies and Connections [S8] and Pedagogy, Care, Community [S9], the book talks of the unending power of friendships to survive, thrive and sustain us during times of need and dire isolation. It is an unequivocal declaration of what makes us human- the need for connection, to feel understood and to be a part of something larger than ourselves. These sections delve into how the pandemic reinforced the significance of female friendships as a pedagogy of care, a site of solidarity and comfort, and a testimony to their strength and endurance- a global pandemic notwithstanding.

Such transcendence is most apparent perhaps in the regional focus of the book, which highlights the strength of bonds across countries divided by arbitrary cartographic divisions but united in a shared (oppressive) cultural experience across borders- which forces us to adopt what Subha Wijiseriwardena aptly calls “South Asian Feminisms” (P12). Friendship, as she reminds us evocatively, is a deeply personal yet powerfully political act.

But, as the other stories show us, it is also a practice- of feminism, of sexuality, of choice, of freedom, of solidarity, of love, of healing and of innumerable other sentiments that have not been given names, but are expressed in various forms through the book- in the dedications to those who changed lives, in letters to those no longer alive, in the last stanza of a poem written as an ode to another self, and in the art peppered through its pages, which leaves so much unsaid. Most of all though, the book tells us- friendship can be anything, with anyone, at any time. It doesn’t have to look a certain way. It just has to be.

This book is undoubtedly an important addition to social-anthropological literature that seeks to foreground South Asian women and queer community narratives, in their voice, presenting a methodological break from convention in much the same way as the recording of oral histories did to the scholarship on Partition. Further, by positioning friendships between womenas a form of intimacy to be analysed independently, it resists the tendency of academic discourses to understand women’s lives in relation to the men surrounding them. While men, romantic relationships and the perils of patriarchy feature in the book throughout, they are peripheral to these accounts of women’s friendships, and the world they inhabit with other women and queer folx, which itself is a political statement, and a practice of the very ethics the book aspires to teach us.

In one of the chapters, Seerat Fatima writes that friendship “is an exercise in empathy” (P320). If the number of passages I underlined reading this book is anything to go by, I would have been friends with a lot of the people writing this book, sharing an understanding that is rare, precious and unabashedly our own.

***

Taanya Kapoor is a doctoral researcher at the University of Oxford, Department of International Development, where her thesis revolves around the contradictions of ‘Modern Daughterhood’ and persisting son preference among the middle and upper middle classes in India since the 1990s. She is passionate about the subject of gender and is currently also part of a comparative research project analysing urban transformation and gender discrimination in India and Johannesburg. In her free time, she runs a monthly, online Women and Gender Book Club through Twitter to discuss all things books.