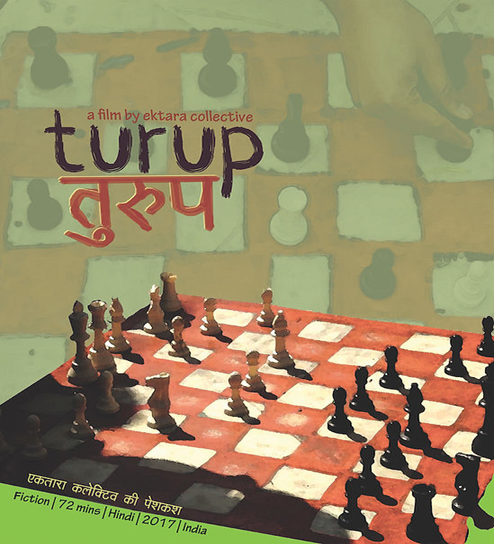

The cinematic immersion in Turup (2017) is a testament to the collaborative efforts of Ektara Collective. It is made by the contribution of the crew and cast, mainly from the working class settlement and crowdfunding. Post the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, it becomes even more crucial to re-visit this remarkable contribution to resistance cinema.

The film is set in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, a city that witnessed a rise in communal tensions and the ‘Love Jihad’ campaign post-2014, with most incidents being reported from the working-class settlements. The central story of the film delves around the lives of three women- Lata, a Dalit woman involved in the caste-based labour of sweeping the streets; Monika, a domestic worker who provides aid to an inter-faith couple in hiding; and Neelima, Monika’s employer, a former journalist grappling with infertility and professional aspirations. Supporting characters of Majid, a migrant driver from Burhanpur striving to make ends meet; Tiwari, a local Hindu right-wing leader whose influence looms large; and Lata’s brother Deepak, who works for Tiwari to propagate and organise local Hindutva politics and mobilisation, add depth to the narrative.

The film employs the game of chess as a potent political allegory, deftly subverting and transcending the boundaries imposed by intersecting factors of gender, caste, class, and religion. Set against the backdrop of Bhopal’s localities, where chess is a familiar pastime, the film brings the game to life in the bustling Chakki Churaha (intersection) on a marble platform beneath a tree, symbolising the complexities of everyday existence. As the chess pieces move, so do the characters that play out an assortment of negotiations in the everyday lives of the people occupying the margins amidst the encroaching spectre of right-wing fundamentalism.

In this male-dominated arena, of players from diverse backgrounds, the initial stirrings of communal sentiment emerge, signalling tensions that build up. Yet, amidst this backdrop, Monika is a compelling presence, weaving her narrative within the confines of the game and her personal life. As she engages with chess in her own space and time, the film underscores the pervasive nature of communal and religious divisions, extending beyond mere surface tensions. Indeed, the film’s central exploration of communal and religious divides is paralleled by the insidious process of “othering” at play, wherein individuals are marginalised based on both caste and gender. These marginalised “others” pose a perceived threat to hegemonic narratives and dominant identities, perpetuating a cycle of exclusion and discrimination.

The intertwining of these identities is vividly portrayed through the backdrop story of an eloped and hiding inter-faith couple. Monika, aided by Neelima’s journalistic connections, seeks to counter the narrative spun by right-wing groups. Meanwhile, one witnesses the complex negotiations and contradictions faced by Lata and Majid, each shaped by their respective caste and religious backgrounds.

They highlight the challenges of sustaining their relationship amidst the escalating fundamentalist climes. Deepak grapples with a constant dilemma as he aligns with a political organisation that claims to unite Hindus while perpetuating discrimination against marginalised groups based on caste and class. In a poignant moment of confrontation with Deepak about marriage proposals, Lata asserts herself, stating, “Paani tak nahi peete mere haath se aur mera kanyadaan karenge (They won’t even drink the water I offer them but want to marry me away).” This assertion encapsulates the film’s broader exploration of diverse identities and political dynamics, probing questions of justice, its beneficiaries, and the myriad ways it operates within society.

The film delves into the subjective experiences of women, shaped by the intersecting forces of their social positioning, to paint a nuanced picture of the development rhetoric of post-colonial nation-building. Through snippets scattered throughout the film, it examines the narratives intertwined with the formation and consolidation of national identity. A poignant scene unfolds

during a discussion on sterilisation, where a doctor urges workers to bring in more women to the camp for more numbers in the government record. This is followed by another conversation between Lata and her friends, where they discuss WhatsApp messages circulating about the perceived threat of the increasing Muslim population and the need to “protect” the Hindu Rashtra by marrying only within the Hindu community without transgressing on “love” and “religion/dharma” of the “nation”.

The film juxtaposes scenes of sterilization campaigns with discussions on procreation and religious demographics, illustrating the state’s control over women’s bodies, particularly those at the margins, through control over the mechanics of reproduction and the perpetuation of communal tensions. In this context, women’s emancipation becomes entwined with a nationalist patriarchy that seeks to redefine notions of femininity and masculinity within the Indian home and domestic sphere.

In the latter half of the film, the unfolding events evoke the imagery and mobilisation sensed in the first half, as announcements and posters for the Virat Hindu Sammelan come into play. This annual gathering serves as a platform for discussions on reviving the dwindling “Hindu culture”, emphasising the importance of preserving the holy cow and embracing Sanatan Dharam as the ultimate goal.

These propagandas, images, and ideals of a unified “nation” resonate both within the film’s narrative and in contemporary discourse, reflecting a narrative rooted in colonial modernity that blends tradition with the rhetoric of development. In this process, gender and its interlocking with caste, class and religion operate as shoulders on which this envisioned “nation” is built and bound to progress, making these structures and categories both historically constitutive and constructed in the power-laden dynamics. Thus, against the backdrop of a looming Virat Hindu Sammelan, the characters navigate a landscape fraught with division and discord. However, amidst the turmoil, moments of connection and resilience also emerge.

The characters, despite their interactions, maintain a palpable distance from one another, serving as a metaphor for the barriers erected to uphold hegemonic cultural norms and knowledge structures. This disconnect isn’t solely observed between dominant and marginalised groups; it’s also evident in the personal struggles of Majid and Lata regarding their social location and perceptions within dominant societal frameworks. Majid reflects on how his religion doesn’t solely define him, while Lata confronts the harsh realities of caste-based discrimination. The essence of the film extends beyond its cinematic visuals to encompass its musical score. The songs, strategically interspersed throughout the narrative, serve a dual purpose: they offer satirical commentary on unfolding events while imbuing the story with allegorical depth, infusing the characters and cinematic experience with political undertones. Despite grappling with shared feelings of isolation, the characters manage to maintain a sense of “self”. Thus, “Turup” transcends its metaphorical chessboard, urging viewers to confront the complexities of spatial and temporal interlocking dilemmas.

The film portrays everyday conversations in the urban neighbourhood, where people grapple with hierarchical structures and navigate the complexities of social, political, cultural, and locational settings. Moving seamlessly from one vignette to the next, the narrative without drawing any long-drawn sequences suggests that the issues addressed transcend the confines of a specific location, resonating on a broader scale. This approach offers a deeper immersion into the multifaceted challenges of contemporary society, drawing from historical legacies to inform present-day realities. By shedding light on these complexities, the film becomes a vital tool for understanding the nuances of contemporary existence and the subjects of inquiry therein.

In the end, this frame speaks to the viewers in its entirety. Amidst various posters on the wall promoting right-wing fundamentalist ideas, Monica proceeds to tear down the one labelled “Bhartiya Naari Kaun Hai?” (Who is an Indian Woman?), thereby rejecting its prescribed ideals and formulations. Ultimately, Turup serves as an essential intervention in knowledge production, offering insights into the region’s struggles with nationalist imagery and hegemonic structures. Through its exploration of contentment and desolation, the film navigates the complexities of nation-building, challenging dominant narratives and inviting viewers to engage critically with prevailing ideologies.

***

Jahnvi Dwivedi is a PhD Scholar at the Department of Sociology, Dr B R Ambedkar University, Delhi.