Post-liberalisation, the Hindi film industry in Mumbai has increasingly embraced stories that portray the lives of the elite to cater to a growing transnational audience (Bhandari, 2017) and this has led to the symbolic annihilation of screen portrayal of diverse social groups within Indian society. In the recent past, there have been sporadic attempts to address this gap in storytelling with films that have aimed to represent either gender or caste issues in Indian society like Badhai Do (2022), Chandigarh Kare Aashiqui (2021), Article 15 (2019), Super 30 (2019) and so on. However, the intersectionality of caste-gender identities in the context of gender violence has rarely been explored within contemporary Hindi cinema. Apoorv Singh Karki’s Hindi film, Sirf Ek Bandaa Kaafi Hai (2023) popularly known as Bandaa is a rare attempt in this regard.

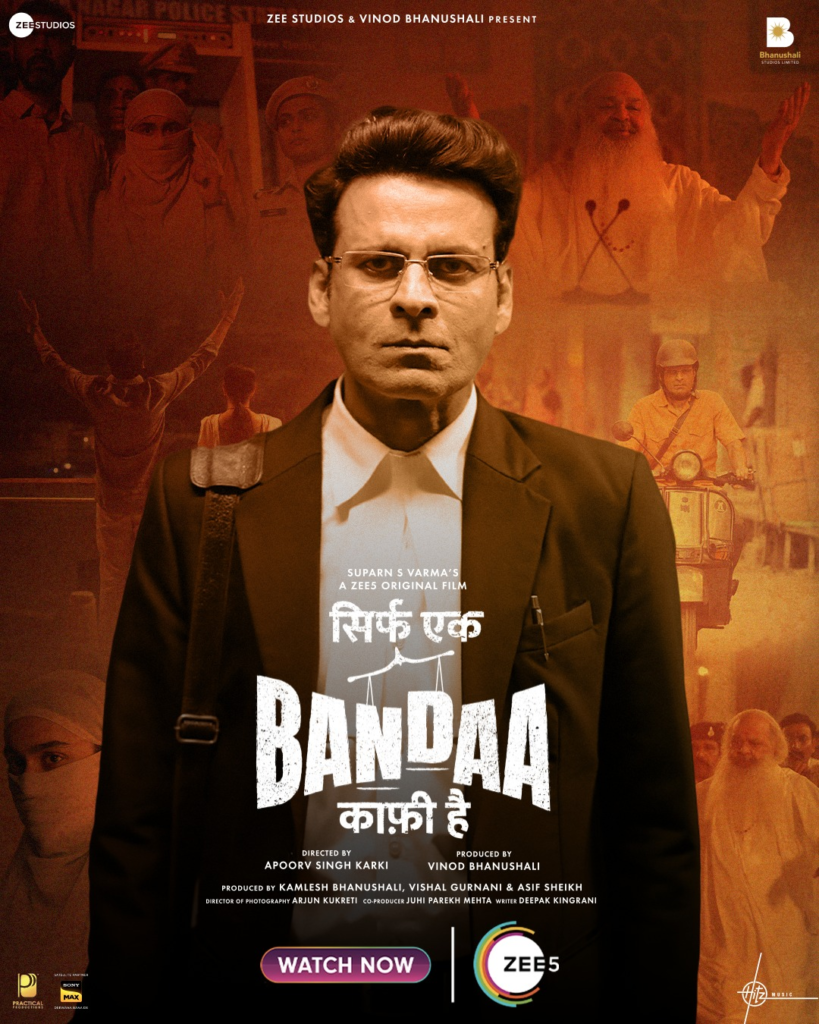

Bandaa is a cinematic representation of the five-year-long (2013-2018) trial of Godman Asaram Bapu who was convicted of raping a minor girl in Jodhpur under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act. Due to the film’s popularity, Bandaa was released in theatre after its initial release on OTT, since then the film has received several nominations and awards including best film, best director and best actor (male) during this year’s award season.

In this re-telling of the trial, director Apoorv Singh Karki uses two types of narrative techniques – one, depicting the events as they unfolded, and the other is a symbolic representation of the dramatic elements within the story. Given the temporal limitation of the trial period, symbolism has been used to expand the narrative space to encompass the ideological as well as aesthetic sensibilities of the director.

At the beginning of the trial, the young rape survivor is shown battling against the marginalization of her many intersecting identities to exercise her agency to demand justice. However, as the narrative unfolds, the survivor’s voice gets overpowered. The narrative progressively eclipses the voice of the survivor as the hero’s (P.C. Solanki) voice, her lawyer, takes over. Solanki is played by the national award-winning actor Manoj Bajpayee, his voice forms the base of the main plot structure. Given the popularity of Hindi film actor Manoj Bajpayee, the film tried to give as much screen time to him as possible. But his representation within the narrative as the benevolent patriarch mostly overpowered the voice of the young survivor. This article will argue that although the intersectional lens was used as a catalyst for storytelling, the caste identity of the survivor was eclipsed by her gender identity thus leaving the caste question looming large within the narrative.

The director has used symbolic representation from time to time to account for the lack of the survivor’s voice within the narrative, like the insertion of a dialogue on a rooftop between Solanki and the survivor towards the climax of the film which mostly evolves into Solanki’s monologue as the scene progresses. In this scene, the survivor is shown to approach Solanki to share her fears about the outcome of the trial. Although this is a dialogue, the screen is dominated by the hero, both in tone and in time. Here the narrative attempts to depict Solanki as an empathizer but his dominance in the scene further underlines the exclusion of the voice of the survivor.

The heteronormative lens used in the representation of gender roles through the juxtaposition of binary gender identities of the survivor and the hero has made space for the emergence of gender identity as a significant part of the narrative of the film. The specificity and repeated underlining of gender violence within the narrative have rendered the caste identity of the survivor invisible. As the portrayal of caste identity is symbolically marginalised within the narrative, it makes evident the politics of representation promoted by the film. Dalit scholar Suraj Yendge (2018) in his article on Dalit Cinema identified that Indian cinema “appears to dutifully genuflect to an Indian Brahmanical order”. Bandaa also follows this trend in Indian cinema, to appease the Brahminical order, the representation of caste identity is almost annihilated, thus the role of marginalised caste identity in the life of the survivor is untouched in this re-telling of Asaram Bapu’s trial. Apart from the mention of Jodhpur Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe Court where the hearing of this case took place, the issue of caste identity has been hidden well within the narrative to render caste as an untouchable subject in Hindi cinema. The process through which cultural texts reproduce power hierarchies within society by failing to represent the voices of marginalised social groups on media has been identified as symbolic annihilation by Gerbner (1972). This is very evident through the politics of identity representation in Bandaa.

As the patriarchal re-telling of the trial reaches a crescendo in the rooftop scene, the survivor is called to embolden normatively hegemonic masculine practices like wielding a sword and calling out to the Hindu male god Mahadev by the hero of the film. Traditionally in Hindu mythology, the female goddess Durga is seen as the symbolic motif for representation of triumph of good over evil. The symbolic use of a female goddess could have perhaps represented the agency held by the survivor. But through the symbolic choice of asking for support from a male deity, any attempt for the survivor’s agency and her multiple intersecting identities to emerge as significant within the space of the narrative was symbolically annihilated.

Overall, the film’s narrative vacillates between the representation of the story of the emancipation of women and the representation of benevolent patriarchy by re-telling an emancipatory story through a predominantly male voice. In this way, the narrative inhibits the screen characters from co-constructing the multiple worlds in which the reality was played out, where the caste identity of the survivor was possibly as significant as or perhaps even more significant than her gender identity. Therefore, despite the noteworthy performance of actor Manoj Bajpayee as P.C. Solanki, the characters in this film were unable to emerge fully to embrace their real selves.

References

Bhandari, P. (2017). Towards Sociology of Indian Elites: Marriage Alliances, Vulnerabilities and Resistance in Bollywood. Society and Culture in South Asia. 3(1): 108–116.

Gerbner, G. (1972). Violence in Television Drama: Trends and Symbolic Functions. Television and Social Behavior. 1: 28–187.

Yengde, S. (2018). Dalit Cinema. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 41(3): 503-518.

***

Sanhita Chatterjee is currently working as an Assistant Professor at Visva-Bharati (A Central University), India. She has completed her PhD in Sociology from the University of Essex in 2022. Her research interests lie in feminist theory, intersectionality, and popular culture.

But while we argue that the caste question (of the victim) has been brushed under the carpet in the movie, we cannot ignore the fact that the advocate on whose life this movie was based, PC Solanki, was a Dalit himself. He chose to contest the hegemony of an acclaimed Godman single-handedly. Portrayal of Dalit characters are protagonists, fighters is a welcome change; although gender question is equally worth-consideration.