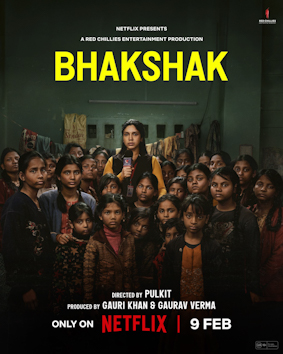

Bhakshak (Devourer) – the 2024 social thriller, directed by Pulkit and produced by Red Chillies Entertainment, is a gut-wrenching portrayal of a horrific reality: the abuse of young girls in a shelter home. It is based on real events popularly known as the ‘Muzaffarpur Shelter Home Rape case’. The story is told through the lens of Vaishali, a journalist who fights to expose the truth in the face of institutional resistance. The movie deals with a variety of different themes, all at once. Some are obvious, and some are more hidden.

Sociologically, Bhakshak is a stark reminder of the vulnerability of marginalised groups, particularly girls in state care. The film exposes the power structures that enable the abuse of young girls and the culture of silence that surrounds it. This is the first, a very obvious layer of the movie- that uncovers gender (and class) exploitation sanctioned by the state. Here is where the movie gets uncomfortable in a more implicit way: it also forces us to confront the role of the media in a capitalist system.

Notably, an opponent of Vaishali’s crusade tells her that ‘the system’ works in complicated ways. Blatant mansplaining aside, it shows that civil society, i.e. media is not considered part of the system. Who remains then to hold the ‘system’ and its institutions accountable? Vaishali’s struggle to get her story published thus highlights the profit-driven nature of mainstream media. As she discovers, hard-hitting investigative journalism often takes a backseat to sensationalised content that garners higher ratings. Presently, Murdoch-inspired Godi media, emblematic of market-driven sensationalism, merely perpetuates the status quo. Civil society, which is dominantly supposed to be non-market, instead bends to its whims. This raises a crucial question: Can we rely on the free market to deliver social justice? Bhakshak suggests not.

Naturally, one might be inclined to think that if the market cannot be relied upon, the state must then be responsible for ensuring proper justice. However, the state is no better. In Bhakshak, politicians, and administrative and police officials are either complicit or complacent about such abuse and exploitation. How then does Vaishali succeed? In the film, a ‘saviour’ character emerges in the form of an IPS officer, Jasmeet Kaur, who takes up Vaishali’s issue. Thus, in another layer, the film also demonstrates the positive effects of reservations and affirmative action, as women in power can help other women in need. Officer Kaur’s position serves as a useful example of how power structures need to be balanced by encouraging more marginalised people in power.

This is no cause for celebration though. Not only does she face immense hurdles, but the very presentation of such processes as magnanimous actions of state actors needs to be questioned. Officer Kaur, extremely sympathetic to Vaishali’s cause, takes up the issue and delivers swift justice. However, the hurdles that Vaishali faced at the local level remain a ground reality across our society. The state, and the police by extension, ought to be compelled to investigate such issues, not out of sorrow or benevolence, but rather by their duty as public servants, accountable to all.

History has shown us, as in the cases of Nirbhaya and Hathras, that mass agitations often compel the media and by extension the state to be cognisant. The fact remains then, that only through mass outrage are cracks in the system revealed, by which abuse is punished. The system still, remains unchanged. Even in Hathras, where many people in positions of power, such as administrative officials, and police officers, were from reserved communities (Teltumbde, 2018), the gang-rape was initially silenced. Likewise, despite being exploited en masse, the women of the shelter home remained silent. It is this culture of silence that the film portrays well. This discursive atmosphere discourages speaking out against upper-caste, upper-class, politically powerful men.

The film doesn’t offer easy solutions. But by placing the issue in the public eye, it compels viewers to question the systems that fail to protect the vulnerable. Bhakshak is a call to action – to demand accountability from institutions, support independent journalism, and advocate for stronger safeguards for children. Bhakshak is not without flaws. However, its unflinching portrayal of social evil and its critique of media’s priorities make it a powerful and necessary watch. It leaves a lingering question: How can we create a society where the most vulnerable voices are heard, and profit doesn’t overshadow the pursuit of justice?

References:

Teltumbde, A. (2018). Republic of Caste: Thinking Equality in the Time of Neoliberal Hindutva. Navayana.

***

Pratyush Rudra is a student of Sociology at Hindu College, University of Delhi.