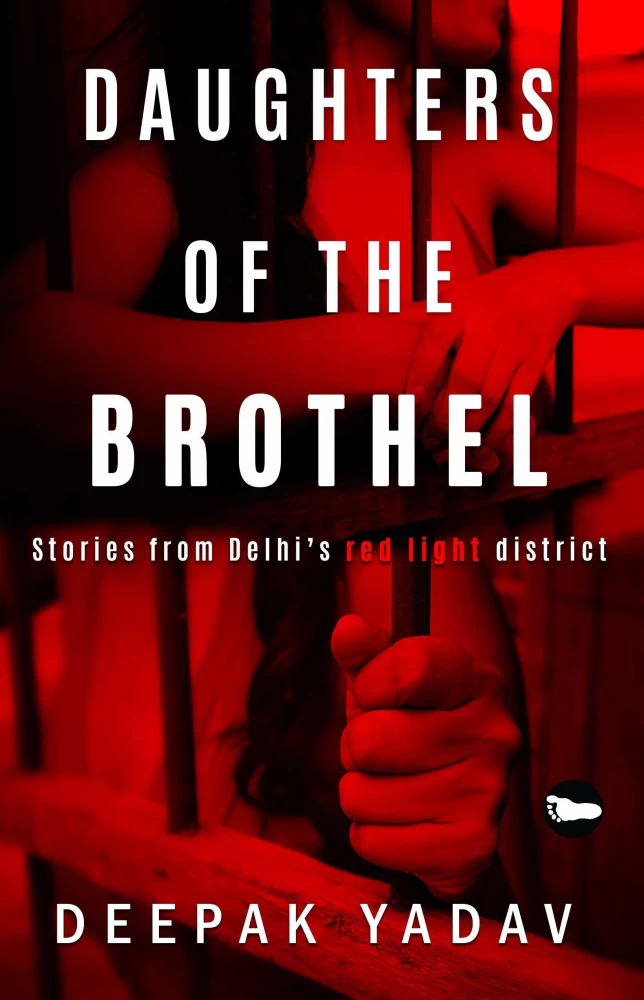

Daughter of the Brothel: Stories from Delhi’s Red-light District (published by Bigfoot Publication in 2022) by Deepak Yadav offers an unflinching look at the lives of sex workers on GB Road in New Delhi. Through the perspectives of law students documenting these women’s lives, Yadav unveils stories of trafficking, exploitation, and survival, shedding light on the systemic and societal forces that perpetuate their suffering.

A journey to the darkness

The first chapter unfolds during a train journey where the writer encounters a transgender person with an unconfirmed ticket. Invited to sit, she shares her story—returning home to see her seriously ill mother before she passes away. Her tale unfolds: her mother was her sole supporter; her father’s acceptance waned upon learning about the woman within his son. Outed by the transgender community, she was separated from her family and taken to a gharana in Lucknow, led by a guru. She discusses castration, a procedure for transgender women, involving genital removal while unconscious. They sit on a grinding stone until they bleed—an initiation akin to menstruation. Despite her contentment, she prays for people to view them without disdain, as such judgment deeply wounds them.

Waiting for monsoon

The second story begins with Kareena, a sex worker who escaped from her abusive husband, twice her age, who used to beat her even after she suffered a miscarriage. The abuse continued until she left and moved to GB Road. According to her, the workers there eagerly await the monsoon season for increased customer traffic, as it’s more conducive to lovemaking. Kareena took the writer to her place to help him understand their lives up close and assist with his book. These workers also hold preconceived notions and stereotypes about each other. For example, they believe Biharis are weak and innocent, citing an incident where a woman was sold by her husband for two lakhs. They consider Assamese to be clever and believe Bengalis are attractive and have unique appetites. Poverty pushes individuals into prostitution, accepting their fate for lovemaking rather than love—that’s the reality. Kareena also shared heart-wrenching truths; children are forced into this life for just two chapattis. She admitted contemplating suicide but couldn’t leave her children behind. Escape is nearly impossible once trapped in this world. Despite numerous health issues, they travel long distances for affordable medical care. Kareena also spoke about the exploitation they face from customers and pimps in the red-light area; she’s never seen a customer tip with a smile. She never returned home after her husband’s death, with her mother-in-law keeping her children. Tragically, her baby girl was murdered by her husband. Kareena’s reflections highlight their courage to endure tragedy and focus on the positive, finding grace through perseverance.

Ladies of the night

The third story explores the purported historical origins of prostitution. It began in Mesopotamia around 2500 BC, where King Sargon recruited women to entertain soldiers during journeys. In ancient Indian society and mythology, Apsaras were revered as high-status prostitutes serving the gods. References in the Mahabharata and Ramayana depict these women as welcoming gods. Rishi Vatsyayana’s Kamasutra outlined eight types of sex workers, with ganikas at the pinnacle, skilled in 64 arts. The Koutilya Arthashastra also elevated their status; in prosperous Pataliputra, they were job holders receiving wages. During the Mauryan era, special officers oversaw the prostitution department. By the 18th century, they were known as tawaifs, with specific establishments like Sonagachi in Kolkata, Kamathipura in Mumbai, and GB Road in Delhi. Prostitution during Emperor Shah Jahan’s reign was limited to five brothels near Chandni Chowk, hosting prostitutes for the nobility’s pleasure. Under British rule, these brothels were relocated to Garstin Bastion Road. In 1965, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri renamed it Swami Shraddhanand Marg. This is of course a sweeping account but offers a sense of the shifting terrians withn which sex work operated.

The story of Fatima begins when her mother left her with her uncle, who sold her to a truck driver for 5000 rupees. Subsequently, she was trafficked to Kamathipura and later to GB Road. Ten years in the brothel exposed her to taboo activities and societal disregard. Girls were trafficked daily, and police apathy prevailed despite knowing the issues. Emotional and physical scars were concealed with heavy makeup as they solicited clients with feigned emotions and postures. Violence was normalized. While society slept, they toiled, earning food in dangerous streets. ‘Ladies of the Night’ vividly depicts their nocturnal lives.

The girl with a golden voice

This story follows a Nepali girl who, after losing her father in an earthquake, faced extreme poverty with her mother and grandmother. She fell in love with a man who promised marriage and a better life in India but instead raped and sold her to multiple men. Eventually, she ended up in a brothel (number 258 on GB Road) after being forced into the sex trade. Initially forced to service 20 clients daily, she was injected with oxytocin to induce menstruation and enhance her physical features. Sadly, her experience is not unique; thousands of Nepali girls are trafficked into India each year, suffering similarly brutal fates. India’s sex trade sees an annual 8% increase, with many victims enduring violence and even death. Despite growing up, Jhumpa feels too changed to return to her family and struggles to trust anyone, haunted by the betrayal and trauma inflicted by those she once loved. Trust, for her, only brings more pain.

The survivor manual

Roopal’s story in the fifth part of the book sheds light on a Bedia community girl who shares her experiences about her medical visits and her shopping trips to the local market. She seeks solace in a Hanuman temple when she grows weary of men. Traditionally, the Bedia community served dance and music to zamindars; after this system ended, these girls were forced into prostitution. The narrative also mentions another sex worker, Fatima, who has a baby named Noor from a man she loved but who tragically died in an accident. Bedia girls often need to stay with a man in brothels or red-light areas for protection in emergencies. From a young age, Bedia girls are trained to seduce men and earn money through prostitution. Marrying is difficult for Bedia girls unless the man has considerable wealth; they often engage in pimping other women. Before entering the profession, Bedia girls undergo a Nath Utari ceremony where they are presented to men for bidding. Roopal was sold for 10,000. The patriarchal Bedia society values the birth of girls but considers having boys unlucky; Roopal’s grandmother abused her mother to death for giving birth to a boy. Reshma, another girl mentioned, is the daughter of a sex worker and granddaughter of a tawaif from Pakistan. Her story includes her mother’s struggle with HIV and her tragic death after being expelled from the brothel. GB Road, as per a report by Sakti Vahini, has 753 workers and serves a total of 8052 clients daily; each woman sees an average of 4 clients daily. The children of GB Road grow up witnessing violence and their mothers’ struggles, shaping their perspectives to reject this lifestyle.

A world of Gods

The sixth story revolves around a Devadasi girl from Karnataka devoted to the goddess Yellamma, yet treated as a mere sex object by those who desire her. This practice persists despite legal prohibitions. Historically, lower-caste girls in the South were coerced into becoming Devadasis in the name of religion. Ganga, one such girl, mentioned the common practice of consuming alcohol to cope with the psychological burden of selling their bodies. Her village has over 100 Devadasis, some relocated to prominent red-light areas in India. Once revered as goddesses, Devadasis are now indistinguishable from typical sex workers, entertaining customers for survival. Upon initiation, these girls’ virginity is auctioned off, and they lose autonomy, obligated to service without refusal.

Daughters of the brothel

Chapter 7 ‘Daughters of the Brothel’ exposes the harsh reality of ageing sex workers in red-light areas. Once they’re no longer deemed productive, they’re relegated to menial jobs within the area, and shunned by society outside due to their past. Owners resort to inhumane tactics to dispose of older workers and evade responsibility. One elderly GB Road inhabitant had acid poured on her while she slept, a brutal example of this cruel practice. Ageing brings physical changes like enlarged breasts, disrupted menstrual cycles, and frequent abortions, jeopardizing their survival. Many end up abandoned, and incapable of bearing children due to past exploitation. Sodomy is commonplace, with disgruntled men targeting sex workers as revenge for personal failures. Fatima recounted how uniformed men often leave brothels without paying. In GB Road, rickshaw pullers are preferred customers over uniformed men.

The twin sisters of Natpurwa

Munni, a pregnant Bedia sex worker, faces community pressure against contact with outsiders to preserve their traditional prostitution. Madhuri’s tragic story unveils familial betrayal, as her mother-in-law sold her into GB Road after she couldn’t conceive, transforming her from an orphan to a prostituted woman, scarred by abandonment and exploitation.

Yadav offers a powerful and unvarnished glimpse into the lives of sex workers, revealing profound injustices and the indomitable human spirit. The book serves as a call to action, urging society to confront these harsh realities and advocate for the rights and dignity of those trapped in the sex trade.

***

Aishwarya Das is a PhD student in the Department of Sociology at Pondicheery University, Pondicherry.