‘Suicide’ among doctors: Data speak

She was a 31-year-old trainee doctor. She was brutally raped and murdered on the night of 9th August 2024 in the seminar hall of the government medical college, R G Kar, Kolkata. The first information of her ‘unnatural death’ was reported as suicide to her parents from the hospital, many hours delayed. Payal Tadvi was a 26-year-old second-year resident doctor in Mumbai who died by suicide on May 22, 2019, in her college hostel, as a result of caste-based harassment and humiliation from her seniors. A first-year postgraduate medical student of a state-run hospital in Warangal died by suicide on December 22, 2023, allegedly due to harassment by a senior male doctor. A second-year postgraduate resident doctor of a private medical college in Tamil Nadu died by suicide in her hostel room on October 6, 2023. Her suicide note suggested facing sexual harassment and mental/physical abuse by the Head of the Department. 27-year-old Supriya died by suicide in her hostel room of the Dayanand Medical College Hospital, Ludhiana on September 29, 2014. The deceased’s father had accused two senior doctors of harassment by not signing her project report, abetting to suicide. While these are only a few newspaper reports, there are very few studies undertaken on doctors’ suicide: its rate is higher than the same in the general population. According to a study (Chahal et al 2022), a total of 358 suicide deaths among medical students (125), residents (105) and physicians (128) were reported between 2010 and 2019. This study did a content analysis of all suicide death reports among medical students, residents and physicians available from online news portals and other publicly available sites. A response from National Medical Commission to an RTi in February 2024, revealed that at least 122 medical students, 64 in MBBS and 58 in postgraduate courses died by suicide in the last five years in India. Gender disaggregated data is unavailable in this but exaggerated duty times (stretching up to 36 hours), inadequate rest, hostile work environment created by toxic seniors, and lack of time off for PG students are some of the reasons for burnout and mental health challenges among the students and doctors in the hospitals, according to the President of Federation of Resident Doctors Association. The gendered consequences of all conditions are unmissable. Additionally, women resident doctors across Kolkata, Hyderabad, Cuttack and Delhi voiced their concerns about the absence of clean, doctor-exclusive washrooms for residents working through the night. Finding places to rest is difficult, except for stools. The presence of Internal Complaints Committees (ICC) and awareness around the anti-sexual Harassment Act seems abysmal with women doctors taking to social media after the Kolkata incident. The point here is not to suggest that death by suicide, rape and murder happen only in the medical profession, while ‘on duty’. The 2022 NCRB figures for rape in India is 31, 000 and reported cases of sexual harassment between 2018 and 2022 were more than 400 each year. As per the same NCRB data, young adults aged 18-30 years accounted for 35% of all suicides in 2022, the biggest share, after daily wage earners, unemployed persons and housewives. Disaggregated profession-based data on any of these violent social phenomena reported in NCRB is always dependent on in-depth research (like Chahal et al above).

In 2001, a fourth-year medical male student died by suicide at R G Kar, the eye of the current storm. Although there has not been any conclusive evidence, it has been rumoured that he had discovered the shooting of pornographic photos and videos in one or more hostel rooms. The mother of the deceased had alleged that his friends and hostel mates were behind his murder. It is well known that suicide on many occasions can be termed as institutional murders and not individual acts of despair. There was an attempt to camouflage the institutional rape and murder at R G Kar as suicide. Like this male student, allegedly she also got to know about “a massive racket involving bribes for transfer postings and an illegal medical syndicate”. More importantly, she “had protested against these malpractices at various forums”.

Workplace rights for women and the medical profession

As feminist legal histories in India will tell us, it was the gang rape of the saathin woman Bhawnri Devi which led to the 1997 Vishakha judgement of the Supreme Court, defining for the first time, sexual harassment of women in the workplace. Post the violent Delhi gang rape of 2012 (incidentally, of a 23-year-old physiotherapy student), besides changes in the rape law; the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) POSH Act of 2013 was enacted. Both the judgment and the legislation assign the employer the responsibility of creating a non-hostile work environment for all women workers. Post POSH Act, it is mandatory to constitute an Internal Complaints Committee in all workplaces. Hospitals or nursing homes are specifically mentioned within the definition of the workplace. The Verma Committee recommendations of 2013 had an important section ‘The Bill of Rights’ for the first time for women in India, ensuring the right to life, security and bodily integrity and the right to secured spaces, all of which are important provisions in connection to what we are discussing.

Together with these legal milestones, this R G Kar incident brings back memories of the Aruna Shaunbag sexual assault by a ward boy of the King Edward Memorial Hospital in Mumbai in 1973, when she was changing her clothes. She became visually and hearing impaired, and in a paralysed vegetative condition until she died in 2015 in that same hospital, cared for by the nurses of the hospital for 42 years, since she was not declared brain dead by the doctors, resisting the euthanasia petition filed by a journalist. A nurse, in 2023, while commenting on the presence of a photograph of Shaunbag at the hospital said, ‘The photograph is a reminder that women need safer work spaces.’ 51 years after the Shaunbag rape, as a response to the R G Kar incident, the National Medical Commission (NMC), Government of India, through a public notice on August 13, 2024, has issued new advisories for all medical colleges and institutions to develop a policy for ensuring a safe workplace environment for all staff members—faculty, medical students and resident doctors. It reads, ’The policy should ensure adequate safety measures at OPD, wards, casualty, labour rooms, hostels, and other open areas in campus and residential quarters’.

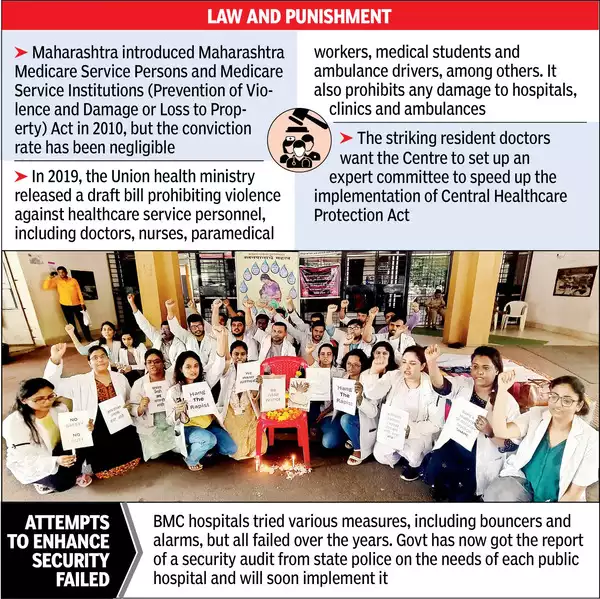

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, has also announced on August 17, 2024, that it will form a committee to ensure the safety of healthcare professionals and revive the discussion on ‘The Prevention of Violence against Doctors, Medical Professionals and Medical Institutions Bill’, which was proposed after the assault on two junior doctors of Neel Ratan Sircar Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata in June 2019. Also known as the Central Protection Act for Doctors, ‘violence’ in this proposed legislation is defined as ‘an act which causes or may cause any harm, injury or endanger of the life of or intimidation, obstruction or hindrance to any doctor or medical professional in the discharge of his duties, or causes to be the reason for any damage or loss to the property or reputation (inordinately) of a doctor, medical professional or a medical institution’ (section 2(f)). The point of reference for this legislation as well as the definition of violence is stated in the Statement of Objects and Reason, ‘[t]he cases of violence against doctors by kins or attendants of patients has become a serious problem off-late compelling many doctors and medical professionals to go out on strike for days seeking security of themselves and their belongings’. Undoubtedly this is an important reason to protect medical professionals from such ‘violence’ as referred to in the ‘Objects of Reasons’ but also from the ‘violence’ as defined in section 2 (f) of the proposed legislation. To address the latter it is necessary to abide by the POSH Act and create and execute policies to prevent everyday harassment and bullying, perpetuating seniority or gender-caste based impunity, and violence. Recently, Dr. R. V. Asokan, National President (elect) Indian Medical Association confirmed that 60% of women are now part of the medical profession, and it is bound to grow. There is therefore an urgent need to ensure a proper, inclusive, non-hostile work environment for them.

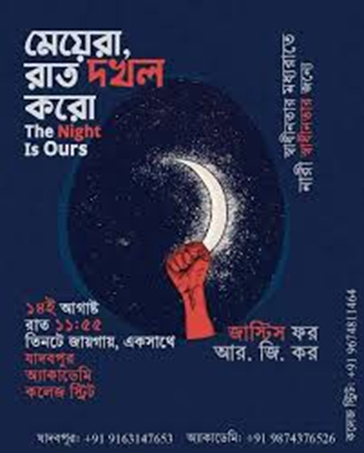

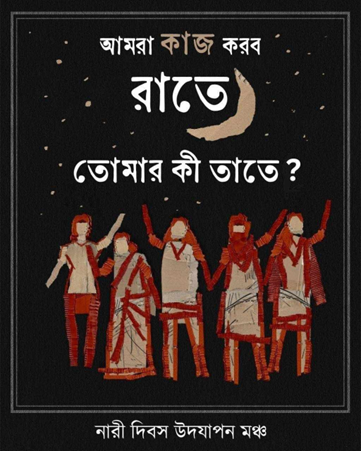

The West Bengal government, as a response to the rape and murder at R G Kar, on August 17, announced a programme to ensure safety for women working in night shift. Rattirer Sathi (Helpers of the Night), deploying women volunteers, proposes a mobile app to be downloaded by all working women connecting with local police, designated toilets in workplaces, security checks and breathalyzer tests to be conducted, women to work in pairs and teams. Finally, the proposal is, wherever possible, night duty for women to be avoided. While keeping women away from night shifts, necessarily will not reduce any gender-based misogyny; ironically, this proposal is in contravention of the 2005 amendment of the Factories Act which allowed women to work between 7 pm and 6 am on the condition that the owner of the factory ensures occupational health, protection of dignity, honour and safety and transportation from the factory to the nearest point of their residence. More importantly, this proposal is in direct ideological opposition to women, queer and trans folks ‘Reclaim the Night’ protests that have been ongoing since August 14, 2024, in all of West Bengal and also in different parts of India. This demand for free and safe access to public space in the daytime, as well as night, is in addition to the demand for proper and safe working conditions in the medical profession by the doctors striking across the country seeking justice in the R G Kar incident. While this new set of proposals has been made by the West Bengal government, it may be relevant to remember two connected facts. On the one hand, Kolkata emerged as the safest city for the third consecutive year as per 2022 National Crime Records Bureau data, recording the least number of cognisable offences per lakh population among metropolises. On the other hand, the West Bengal government has utilized only 3.9 crore of the 76 crore fund allotted from the Nirbhaya Fund, till 2019. There has been an announcement made by the West Bengal government to utilize the majority of this fund under the ‘safe city’ project, including CCTV surveillance, the creation of mobile toilets, setting up a cyber crime investigation lab, and a sensitization programme for boys in schools. It needs to be mentioned that most states across the country have underutilized the Nirbhaya Fund, as per data shared by the Ministry of Women and Child Development in 2019. Overall utilization stands at 11% with Uttarakhand and Mizoram spending 50% of the funds while West Bengal, Maharashtra, Gujarat and Tamil Nadu utilize less than 5%. It remains to be seen whether the West Bengal government’s announcement will eventually be passed as an order and use the underutilized Nirbhaya funds.

Risk, Resistance, Resolve

These two posters represent the ideology and response of the movement post the incident. Giving a call ‘The Night is Ours’, is reminding us of Walk by Maya Krishna Rao, a passionate performance post the Delhi gangrape and reflecting on the night marches that happened across the city of Delhi. Unlike the critique that these night marches are only meant for urban cities, this time North 24 Parganas, Siliguri, Durgapur, districts of West Bengal, all had night marches including pockets in Kolkata not commonly associated with protest marches. The Nari Dibash Udjapon Mancha (Platform for Women’s Day) has come out with a poster affirming ‘What is your problem if we work at night?’ Medical professionals per se and women specifically are working in conditions of high risk, pressure, and hierarchy. ‘Resident’ doctors are at risk inside their residence or home i.e. the hospital, which is also their workplace. The 31-year-old deceased woman called the hospital her ‘second home’. She was brutally raped and murdered inside the seminar hall of this second home, after a shift of continuous 36 hours, when she had fallen asleep. The first publicly available response on the incident occurring inside Radha Gobinda Kar Hospital, (established in 1886 as Calcutta School of Medicine and renamed after its philanthropic founder in 1948) made by its Principal was a lie–the lie of suicide. Not all deaths evoke resistance. However, some gruesome acts of sexual violence and murder led to nationwide protests. As the details of the nature of her torture, rape, resistance and death come in, we wait for all the culprits to be identified, and arrested and for trial to commence. A senior cop has already remarked that even when half-asleep, she tried to fight back. She had tried to resist and cause deep injury marks and scratches in the hands of the accused. The scratch injuries on the accused body matched the skin and blood samples collected from the fingernails of the woman doctor. While we hope that justice will be delivered in this particular case; ironically Asha Devi, mother of Jyoti Singh asked ‘What have we learnt from the Nirbhaya incident? What changes have we made to the system? We are still stuck in 2012.’ As the Supreme Court pronounces on August 20, 2024, ‘the nation cannot wait for another rape for things to change on the ground’, paying comprehensive attention to the risks with which those in the ‘noble profession’ work and facilitate long-term transformation is certainly the immediate need of the hour.

Reference:

Chahal S, Nadda A, Govil N, Gupta N, Nadda D, Goel K and Behra P. (2022). Suicide Deaths Among Medical Students, Residents and Physicians in India Spanning a Decade (2010-2019): An Exploratory Study Using Online News Portals and Google Database. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 68(4):718-728.

***

Rukmini Sen is a Professor of Sociology at Dr B. R. Ambedkar University, Delhi.

Excellent. Humane. The problem is the lack of education on the part of the government to understand such expositions despite highly qualified women and men in bureaucracy.