The Gulf always reminds me of my mother’s recurring tales of how her uncle, who migrated to the Gulf from Kerala, would bring her beautiful, long skirts whenever he visited home. The narratives of Gulf migration in Kerala are largely personal and persistently revolve around themes of consumption, poverty, economy and remittances. Mohamed Shafeeq Karinkurayil’s The Gulf Migrant Archives in Kerala: Reading Borders and Belonging (published by Oxford University Press in 2024) is a pioneering work, a timely reclamation of migrant histories and sheds light on the often erased and indispensable popular culture aspect of Gulf migration in Kerala. Karinkurayil curates photographs, popular songs, cinema and literature in the Malayalam language to critically evaluate the construction of the Gulf in the dialogues and creativities of the Kerala public sphere. The book explores the many ways the Gulf is presented in the imaginaries of Kerala, drawing attention to the dissonances between fantasies and social realities, private and public domains by analysing cultural records of Gulf migrants.

The introduction sets out the book’s central premise by raising some pertinent questions; why is the Gulf characterised as a rumour in Kerala? Why is writing on the Gulf identified as writing about the borderland? Karinkurayil underscores the prosperity of the Gulf, which has prompted extensive migration, as a subject of rumour. The rumour stems from the Gulf’s lack of visibility in the public discourse in Kerala. The Gulf was, as Karinkurayil notes, “a genre considered private, with all its force, emotions, and affect, but devoid of a public language other than that of remittance” (p.15). At its core, the book emphasises the possibilities of Kerala and the Gulf functioning as borderlands where migration is produced and shaped by ‘epistemic faultlines’ (p.28). The continuities lie in literary and visual narratives where the fault lines at home are transported to the Gulf in the same way transactions from the host are perpetuated in Kerala. The book is revelatory in its stance, highlighting largely overlooked theorisations of circular migration and the rising significance of regions over nation-states to provide an in-depth understanding of the life and experiences of Gulf migrants through cultural archives in Kerala.

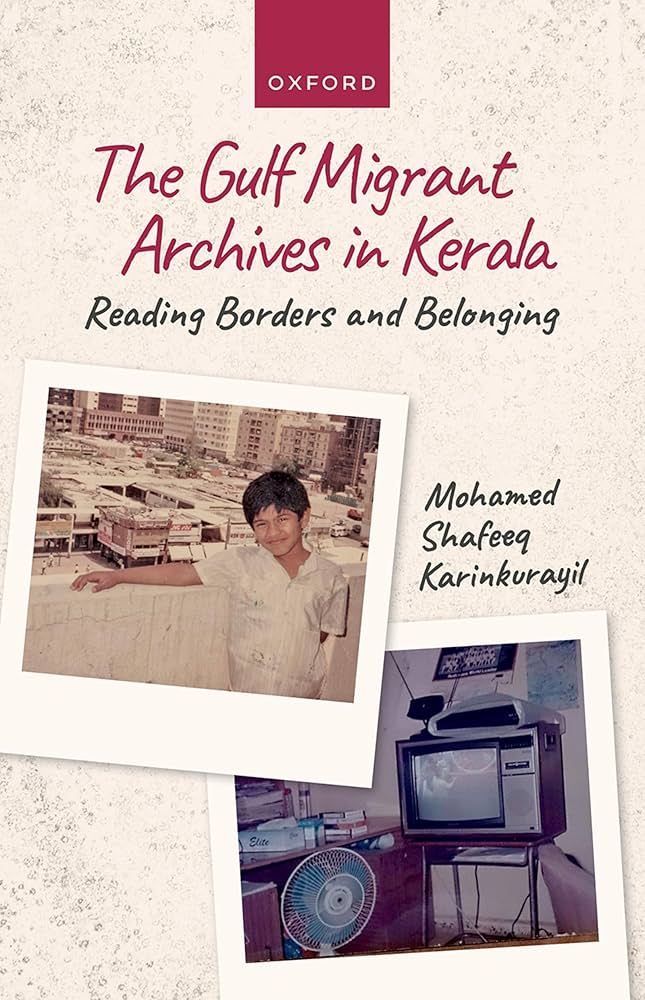

The book is organised into four parts, Karinkurayil selectively compiles and documents migrant narratives and the Gulf experience in literature, films and photographs. The chapter on photography details the impact of Gulf photographs in personalising the Kerala migration episode, showcasing the Gulf’s materiality and modernity. A photograph from the year 1981 reviewed in detail in the chapter considers the migrant at leisure, it illustrates mimicry, thrills of city life, youth culture, consumerism and various modes of viewing migrant photography. The depiction of the Gulf in Malayalam cinema is primarily informed through films such as Vilkkanundu Swapnangal (1980), the Home Cinema of Salam Kodiyathur and the laughter films of the 1980s to mid-1990s (Akkare Ninnoru Maaran, 1985). While Vilkkanundu Swapnangal revealed an up-and-coming migrant in the Gulf, the late 1990s witnessed the Home Cinema of Salam Kodiyathur which established a novel cinematic genre similar to middle-brow movies in Malayalam. Kodiyathur’s films presented the Gulf migrants’ perspective, which, as Karinkurayil points out, foregrounded the weakening of traditional values, anxieties about consumerism, and the vulgarities in visual culture from the Gulf migration. The laughter films underscore the Gulf’s representation as a public secret and a land of immense fortunes and instant prosperity in Kerala, which was contested by movies in the closing years of the 1990s. Karinkurayil discusses this reimagining of the Gulf as a ‘realistic space of labour’ by citing movies such as Shutter (2012) and Pathemari (2015) (p.82).

Chapters three and four of the book examine migration literature from Kerala and invoke the temporariness and in-betweenness of migration. It answers how Gulf migration contributes to the formation of collectivities and continuities by focusing on Sageer’s comic strip Gulfampadi PO (started in 2001), Khadeeja Mumthas’s novel Barsa (2007), Krishnadas’s book Dubaipuzha (2001) and Sonia Rafeek’s novel Herbarium (2017). The chapters offer us profound connections between these migrant writings by traversing through aspects of everydayness, acts of memory and cosmopolitanism. By introducing the works of Benyamin (Aatujeevitham/Goat Days, 2008) and Deepak Unnikrishnan (Temporary People, 2017), Karinkurayil advances further to illustrate the disruption of language, realism and formation of communities through exclusions and untranslatability in migrant literature. For instance, the Arabic words in Goat Days remain indecipherable to the reader, who enters the world through Najeeb (Malayali Gulf migrant protagonist) for whom the words are undoubtedly incomprehensible.

The book The Gulf Migrant Archives in Kerala sheds light on the long-overlooked reality of the cultural dimension of labour migration from Kerala. Karinkurayil challenges the individual-centric narratives of Gulf migration and effectively questions the glueing of the migrants into the economy. The book centres on how the Gulf has been treated as a secretive realm and excels in compiling literary and visual cultures to provide a detailed analysis of the transition of the Gulf from a secret to entering the public discourse in Kerala. The time leap in the study of Malayalam cinema from 1980 to the present may warrant critical scrutiny. The book is indeed a refreshing take on Gulf migration in Kerala; the dialogue on Islam and visual culture, connectivities of home and host and renditions of migrant/ foreign are significant. One of the greatest strengths of the book is its aim to build and preserve the Gulf migrant archive in Kerala and in this pursuit, it reclaims migrant history in its truest sense.

***

Amratha Lekshmi is a PhD Research Scholar at the Centre for the Study of Social Systems (CSSS), Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi