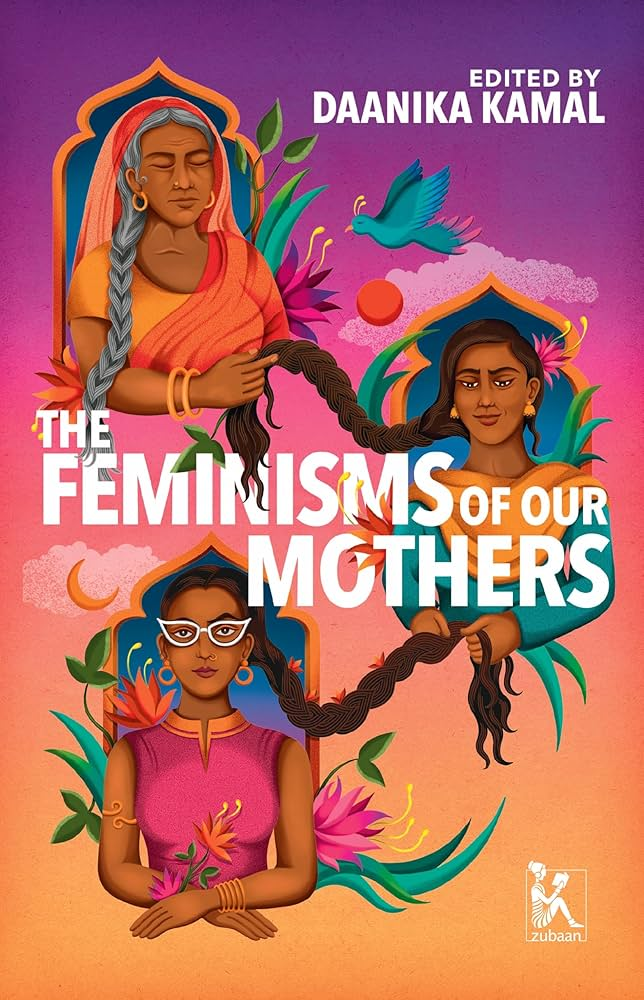

Daanika Kamal’s collection of essays The Feminisms of Our Mothers (published by Zubaan in 2024) introduces us to the complex world of mothers and daughters in Pakistan. Women are often compared to their mothers on how they look, their choices and how they carry themselves, whilst they constantly try to make themselves independent from them. Aurat March of Pakistan becomes one of the significant examples through which women in this collection of essays endeavour to imagine their relationships with their mothers.

The experience of feminism is unique for Pakistani mothers. Saadia Ahmed accounts for its unpopularity because of its association with Western imperialism in Pakistan, akin to other non-European nations. Further Amna and Mariam Shafqat point out how feminism is thought as too alien and unrealistic to apply to the lives of Pakistani women. The book also points out how Indigenous women’s struggles are often unacknowledged in mainstream feminism. This negligence needs to be examined as these women are survivors rather than victims of patriarchal structures.

The first essay by Maham Javed plunges into the life lessons that she derived from her mother. The author often chose to align with her father over her mother. Her father then used to argue how women’s work is fusool kaam. Javed borrows from Bonnie Burstow to argue how the father and daughter look down upon the mother figure as not as bright as them, and the daughters too later end up with the same fate. It is from her mother that Maham learnt radical, unconditional love, full of hope. But her mother also made her feel that her self-worth in terms of love and marriage was associated with her weight. This is in opposition to Sabah Bano Malik’s experience whose mother let her be unabashedly herself in her weight. She never allowed Sabah to be stuck with their insecurities and wanted her to fight her shyness though she was a shy person.

Maria Amir’s essay reflects on how women eventually turn into their mothers. Either they rebel and understand them later, or they consciously invoke them. She also divides mothers’ negotiation with intergenerational trauma into two shapes – circles or squares. Women like circles want values to persist as a means of survival in patriarchy. Unlike circles, squared women would not want their daughters to go through what they had to go through and would try to stop it. This trauma often becomes evident as rage, which is not understood even by their daughters. Daughters offer their mothers very little compassion when they express rage and pain.

Another significant issue in the essays is the differences that exist between mothers and daughters. Zoya Rehman’s mother has resisted and pushed many boundaries by being a black sheep of the family. But Zoya became a disappointment for her mother as she did not conform to her expectations. Her love was conditional as she wanted her daughter to be her exact copy. Their relationship becomes a symbolic space for hope for the feminist movement itself, to transcend the differences that exist within to reach its potential. Similarly, Amna Baig details how she detached herself from her mother as she wanted to not conform to the patriarchal future around a man, and live independently. As a result of this, her mother imposed more strictness, but ultimately, she let go of all this to unlearn the structures within which she was trapped. There are also radical mothers as evident in Manal Khan’s life, whose mother was a working woman. She was considered an awara against ‘good’ women who spent their time looking after their husbands and children. Her mother’s values made her strong, despite her mother fearing for her well-being in protesting against traditional mores.

Kamal’s essay discusses intergenerational feminism. For her Nani, the greatest aspect of a woman’s identity is that of respect. Her mothering was unique as she brought up her daughters akin to sons. Nani’s mother Nannajan opposed this, but she too was a feminist because she used to avoid proximity with young brides. This is because she knew the suffering of being a widow and wanted to protect other women from the hardship that she experienced, not wanting to cast a shadow on them. Kamal’s mama too faced difficulties in getting along with her in-law’s family. She decided to walk out of that situation because her feminism made her believe in women’s independence and autonomy.

Women are expected to do emotional work, which according to Amna and Mariam Shafqat is not even considered as labour. Maheen Humayun’s mother never felt at peace until she took care of everyone. This is reflected in Maheen herself as the elder daughter as she too felt the need to control and fix things. Aiman Rizvi’s experience with her mother is another example of women and emotions. While Aiman herself indulged in pleasing vocabulary, she found her mother making uncomfortable conversations, putting others in distress. Rizwi finds Sara Ahmed’s argument significant in this context. Ahmed argues how a possible space of activism emerges from the space between what one is supposed to feel and what one feels. Aiman’s mother’s acts caused unhappiness and discomfort by not feeling what she was supposed to feel, going against her social role as a mother.

The social pressure among mothers to make sacrifices has been examined in Ayesha Izhar’s essay. Women are naturally expected to make sacrifices, even for simple chores. This makes these mothers trapped within their minds. They are even supposed to explain their mobilities. Daughters seeing their mothers’ condition would never want such a life for themselves, leading to differences in opinion.

These differential experiences of daughters and mothers could be accurately summed in Alice Walker’s quote- “In search of my mother’s gardens, I found my own.” This text thus becomes a significant addition to non-fictional literature on motherhood in the South Asian, specifically Pakistani context.

***

Himaganga Joji is an independent researcher.