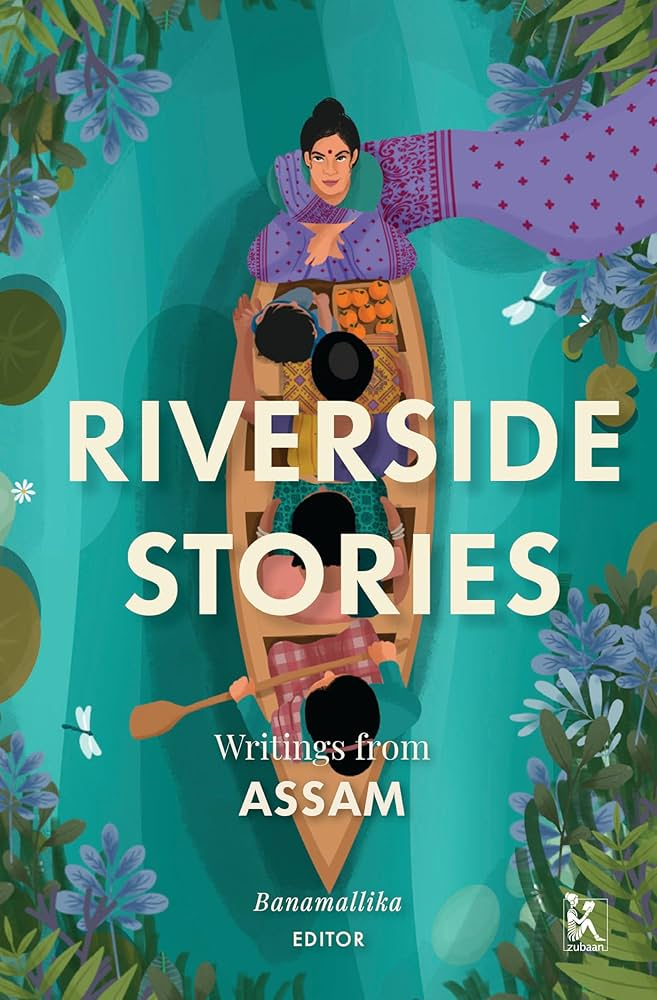

Riverside Stories: Writings From Assam is an anthology of poetry, prose, illustrations, and graphic art collected by Banamallika and published by Zubaan Books in 2024. All the contributors to this anthology are women and trans individuals from Assam. The editor Banamallika introduces the book with a discussion of the roots of the word ‘anthology’, tracing it back to anthos meaning ‘flowers’ and logia meaning ‘collection’. Referring to Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s work, she says that an anthology–a collection of flowers of verses– inherently possesses selection and exclusion in its nature. Therefore, a book about feminist narratives of ‘women in Assam’, invites the questions of inclusivity: “What is a woman?” and “Who is Assam?”. The texts and images of this anthology, individually and as a collective, deconstruct, extend, contest and reconfigure the dominant patriarchal definitions of these terms. The book contains a plasticity by not organizing its contents based on genre or themes. Like a river, the chapters flow from one poem to a story, then make a turn before splitting into illustrations, and then taking the form of a poem again. The contributors of this narratorial river work as academics, journalists, homemakers, activists, designers, and artists. Their writing and visuals carve out a vulnerable personal space which is separate from their profession and invites the reader to be a guest at their home.

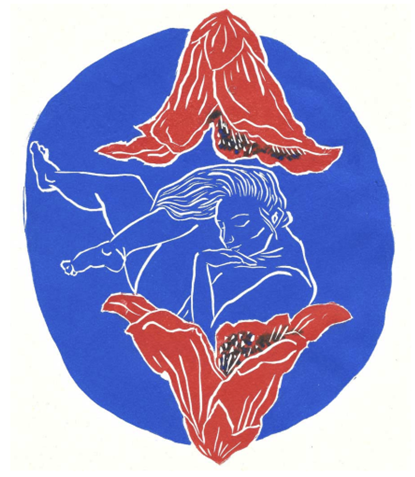

There are a total of thirty-nine chapters spanning across different media and genres in a 200-page landscape. A key feature of this anthology is the vivid bricolage of the form of these short chapters that morphs the established literary genres. For instance, Rituparna Neog’s “Better Being A Scarecrow”, and Rashmi Rekha Borah’s “Champawati” are freestyle prose poetry with pencil sketches portraying the metaphor of Assamese womanhood and intrusive gaze. Pranami Rajbangshi’s “Self Portrait” expresses the experience of objectification through a poem embedded with photographs. On the other hand, Sangeeta Bhagawati chooses a non-verbal lino print to illustrate the stages of growth as a woman in “Bloom”:

Figure 1: Ximolu by Sangeeta Bhagawati

Furthermore, there exists an organic nonuniformity of the style in the interplay of images and text. Some images possess the finesse of an art gallery exhibit while the others resemble a leaf taken from the last page scribbles of a notebook. This contrast elevates the collective to a sense of personhood rather than being a decorative aesthetic of a literary publication.

Figure 2: The contrast of visual artwork folded between chapters of prose and poetry

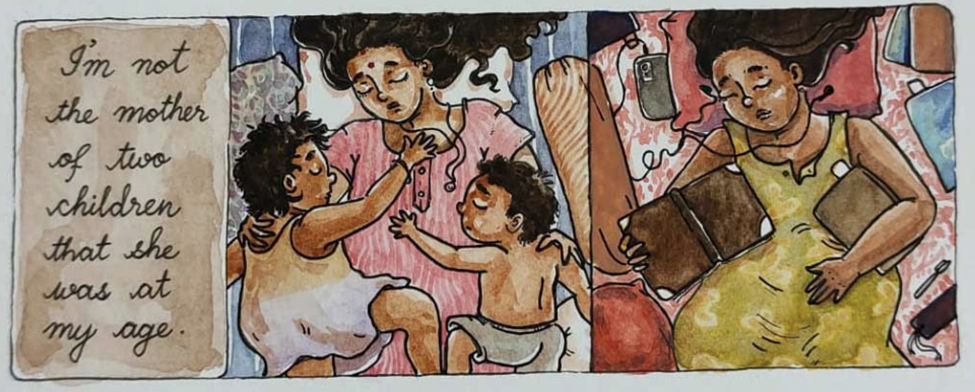

The diversity of thought creates a multiplicity of Assamese feminisms. Such as Tara Shivani Goswami’s “Shyla”, showing the difficulties of coming out as asexual and Lucky Neog’s articulation of living as a trans man who menstruates in “Menstruating Man”. Madhusmita Mukherjee’s humorous story “Taar/Tair” queers the boundaries of Assamese/Bengali/Hindi languages and says confusion is liberating. Especially when “patriarchy tries to force binaries on us, the confused in-between—neither a Bengali, nor an Assamese, nor a girl, nor a boy”, is darun[i].

Figure 3: A frame from Reetuparna Dey and Anindita Kar’s graphic narrative “Unbecoming”

Sabrina Iqbal Sircar’s prose “Being Axomiya, Muslim, and a Woman” takes the discussion of womanhood from body to state and religion. Sircar narrates incidents from her life to show the paradox of identity, or as she puts it “You are not an Axomiya if you are a Muslim and you are never Muslim enough if you are an Assamese”. The political turmoil of citizenship in Assam is also discussed in Nasmin Choudhury’s “The Red File” and Chaity Das’s “Joba” in the present time as well as reverberations of the 1970s Bengal partition. The anthology knits the political conflict of Assam with the ecological woes of recurring floods that annually reshape Assam’s landscape and the lives of its people. In Rashida Tapadar’s “Manowara’s Library,” the floods are both a curse and a blessing, providing more vacation time but also inspiring the creation of a floating library to spread education. Maitreyee Boruah brings out the feeling of claustrophobia of being stuck on flooded roads in “Pungbili”. The metaphor of the river connects all the stories, poems, and artworks of the collection. During rains when the water rises, the boundaries of land, languages, gender, and time are inundated. As Banamallika puts it, “ In Assam when the water rises, we rise along with it. Sometimes we make it, sometimes we don’t. Telling our stories all along”.

[i] Bengali word for wonderful

***

Rahul Bishnoi is a performance studies researcher working at MICA (Ahmedabad).

How rootless watee is and yet so unifying? Shape-shifting evermore