A few days ago, I was travelling in a car with my family and we passed by a famous park in the city. I commented I had never been to that park and a family member replied, “Don’t go there, it is for pairs”. This was symbolic of how some places garner a reputation for being “pair friendly” or designated spots where “immoral activities” take place; PDA (Public Display of Affection) is synonymous with immorality in this instance and hence these places become those that people purposefully avoid.

Although, PDA is often met with scrutiny in the form of moral policing where couples are attacked, chased or harassed by mobs and vigilante groups who believe PDA to be “immoral” and opposed to “Indian culture” (Basu, 2014; The Quint, 2018); it is a common sight to see couples engaging in varied forms of sexual and romantic gestures in public: from holding hands to kissing and more.

Some common places that are go-to destinations for couples include parks, gardens, monuments1, cafes, clubs, movie theatres and even the metro (Sengupta, 2023). Moreover, shopping complexes such as Dilli Haat2, parking lots of Saidulajab and Cyber Hub3 are also deemed romantic places for couples in Delhi-NCR. Many of these places are even marketed as such by listicles in magazines and newspapers catering to the youth4 and websites giving travel recommendations5. Therefore, the growth of these consumer spaces has aided the formation of an urban ‘middle-class’ sexuality (Annavarapu, 2018; Phadke, 2005). Interestingly, consumption trends and patterns in recent years have made movie theatres a preferred public space to express intimacy.

Last year, I went to a nearby movie theatre to watch a movie with a friend and saw an advertisement in the theatre saying that one could watch trailers for 30 minutes for just one rupee. It seemed bizarre to me that movie tickets generally cost much more and to watch trailers for just a rupee was unheard of. The next few times I went to the theatre I saw the same advertisement but did not pay much heed. Earlier this year, I decided to watch the 30-minute trailer show. However, it dawned on me only after entering the theatre, that it was a couple-friendly space; as it was dark, air-conditioned, inexpensive, had comfortable seating, was free from any possible mob thrashing and in fact, no one there was watching the trailers.

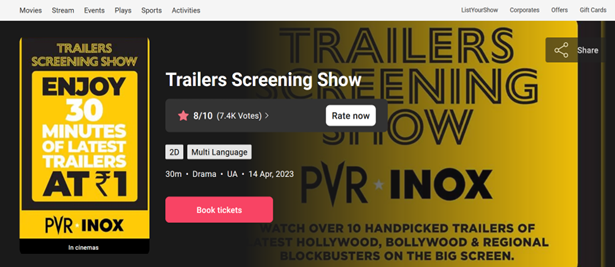

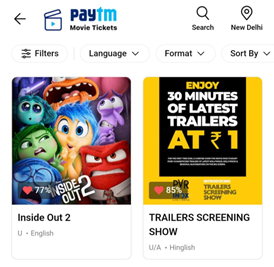

Snapshots of 30-minute trailer show booking on e-commerce websites and its high ratings

On 7th April 2023, multiplex giant PVR INOX launched a scheme of watching movie trailers for 30 minutes for just one rupee across various states within the country. This was done to increase ticket sales and bring back audiences to the cinema hall as in-theatre movie sales had starkly decreased after the Covid-19 pandemic (Jain, 2023). This scheme was based on the product sampling strategy often followed by FMCG (fast-moving consumer goods) companies wherein free samples are provided to shoppers to drive sales. The product sampling method capitalises on consumer curiosity and impulse buying behaviour by capturing “the attention of potential buyers who are already in a shopping mindset” (Cross, 2023).

Alok Tandon, co-CEO of PVR INOX commented, “The intention behind introducing this world-first feature is to innovate on the content front and offer what we call ‘snackable content’ at unprecedented pricing” (Hariharan, 2023). Snackable content is short and easily digestible content designed for quick consumption. It encourages sharing and interaction as it is easily consumable and captures attention (Team Storyly, 2024). Moreover, many cinema halls have reclining chairs6, alternate pairs of which do not have a movable tray on the armrest between the two seats, allowing for more comfort when fully reclined. While movie theatres might already have been a preferred spot for couples, the 30-minute trailer show made it exponentially more affordable, especially for young people who cannot always access other spaces for intimacy. “In these moments, a public space – a hole in the wall, a deserted road – turns into a romantic getaway” (Chaudhuri, 2017).

In this way, the strive for increasing consumption led to the creation of spaces and trends that allow for the public expression of intimacy, representing a ‘middle-class’ sexuality that is both progressive and respectable (Phadke, 2005 cited from Annavarapu, 2018), stuck between the traditional and modern at the same time (Srinivasan, 2017). “New social structures and values are fast making their way into the urban lifestyle. But the old ones aren’t disappearing,” said photographer Gayatri Ganju who documented public intimacy in India in her photo series titled Strictly Do Not Kiss Here (Chaudhuri, 2017).

Another concept that is worth exploring in the context of public intimacy in India, is the idea of liminality. The term liminality was first introduced in 1909 by ethnographer Arnold van Gennep to refer to an intermediary ritual phase marked by blurred boundaries and ambiguity. It originates from the Latin word ‘limen’ meaning threshold (Scott, 2014). Going beyond the ambit of sociology and anthropology, the concept of liminality has been used extensively. It signifies the in-between, transitionary and transformative periods, borders, and interstices. This state of ambivalence is akin to the character of public intimacy in India, somewhere in between the mores of tradition and modernity.

In terms of places, the notion of liminality has been invoked variously. Seaside and beaches are quintessential liminal landscapes, existing between land and water. Beyond academics and research, the aesthetic of liminal spaces became popular as an internet trend in 2020. The liminal space aesthetic revolved around posting images of places that were devoid of people, limbo-like and eerie such as labyrinthine hallways, abandoned buildings, empty corridors, backrooms and so on. This trend even led to the creation of various subreddits where users shared pictures of liminal spaces (Pettie, 2023).

In 1991, Rob Shields put forth his thesis on marginal places and liminality. He used the concept of spatialization to analyse the role of cultural meanings and power relations in the creation of spaces. He gave the example of Brighton Beach, where people engaged in sexual intimacy as the weight of social relations was symbolically lifted in this marginal zone. The norms of high culture were inverted in Brighton, making it “the ideal location for a brand of “dirty weekend” characteristic of the 1930s’ middle classes” (Ogborn, 1991, 496).

However, I believe, the concept of liminality can be taken further in discourses of public intimacy vis-à-vis the degree of privacy provided by the place of choice for public intimacy. Parks, cafes, monuments and shopping complexes are desired spots for the expression of public intimacy despite not offering complete privacy: other private spaces being inaccessible being the primary reason while exhibitionist tendencies may be a minor reason for the same.

However, these places are also preferred because they offer a liminal degree of privacy. Neither too many ogling eyes and peeping toms, nor an entirely deserted domain. While the former may result in judgment and discomfort, the latter raises concerns about safety and risks of street crime. Secluded public spaces are commonly regarded as exposing people to criminal risks for being the haven of squatters, voyeurs, thieves, chain-snatchers, robbers and other criminals (Garg and Singh 2023). Similarly, Kevin Meethan (2012) has described beaches as ‘edge spaces’ offering both comfort and danger. On one hand, beaches may be rowdy places of amusement and fun as spaces for recreation for both tourists and locals. On the other hand, beaches can be extremely hazardous, a place of transgression due to smugglers and pirates.

While Meethan places people engaging in “risqué behaviour” at beaches in the latter category of potential causes of risk as they have shed their inhibitions characterised by a “lax sexual morality” (2012, 70); these in-between places formulate perfect zones of liminality for them. From the point of view of the pairs, these liminal locations blur the boundaries of morality and proffer just the right amount of privacy and an unsaid tryst with safety. The ambivalent, interstitial spaces of liminal privacy become the destination for the quest for public intimacy.

https://www.universaladventures.in/travel-guide/romantic-places-in-delhi

https://www.dutimes.com/best-places-get-cozy-delhi/

https://www.thrillophilia.com/places-to-visit-in-delhi-for-couples

https://www.holidify.com/pages/romantic-places-in-mumbai-340.html

https://www.reclinersindia.com/cinema-recliner-chair-installed-at-pvr-insignia-delhi/

References:

Annavarapu, Sneha. 2018. “Where Do all the Lovers Go? – The Cultural Politics of Public Kissing in Mumbai, India (1950–2005)”. Journal of Historical Sociology, 31: 405–419.

Chaudhuri, Zinnia. 2017. “Scottish Lolitas and Dating in India: Photographers From Two Nations Capture Critical Moments.” Scroll. June 19, 2017.

Cross, Mollie. 2023. “The Best FMCG Product Sampling Methods for Brands.” Relish. October 31, 2023. https://relishagency.com/blog/fmcg-product-sampling-methods/

Garg, Prarthana & Raja Singh. 2023. “Analysing Crimes in Public Spaces of New Delhi Through News Reports: The Need and Possibility of Integrating Crime Prevention through Environmental Design Principles.” Qeios. https://doi.org/10.32388/I9NNFW.6

Hariharan, Sindhu. 2023. “PVR INOX Introduces a 30-minute Trailer Screening Show at Re. 1.” The Times of India. April 14, 2023. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/pvr-inox-introduces-a-30-minute-trailer-screening-show-at-re-1/articleshow/99482563.cms

Jain, Rounak. 2023. “What Can ₹1 get you? 30 minutes of Trailers at PVR Inox.” Business Insider India. April 14, 2023. https://www.businessinsider.in/entertainment/news/what-can-1-get-you-30-minutes-of-trailers-at-pvr-inox/articleshow/99487702.cms

Meethan, Kevin. 2009. “Walking the Edges: Towards a Visual Ethnography of Beachscapes.” In Liminal Landscapes: Travel, Experience and Spaces In-Between, edited by Hazel Andrews, Les Roberts, 69-86. London and New York: Routledge.

Ogborn, Miles. 1991. “Book Review: Places on the Margin: Alternative Geographies of Modernity: Rob Shields.” Journal of Historical Geography, 17 no. 4: 495-497.

Pettie, Earnest. 2023. “Liminal Spaces May be the Most 2020 of all trends.” Ernest Pettie’s Rough Draft. September 6, 2023. https://earnestpettie.com/essays/liminal-spaces-may-be-the-most-2020-of-all-trends/

Phadke, Shilpa. 2005. “You Can Be Lonely in a Crowd” The Production of Safety in Mumbai.” Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 12(1): 41–62.

Scott, John. 2014. Oxford Dictionary of Sociology. 4th ed, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sengupta, Trisha. 2023. “How Delhi Metro Replied to Viral Pic of Couple’s PDA During Commute.” Hindustan Times. 21 June 2023. https://www.hindustantimes.com/trending/how-delhi-metro-replied-to-viral-pic-of-couple-s-pda-during-commute-101687346539671.html

Srinivasan, Shalini. 2017. “A Photoseries that Captures the Politics of PDA in India.” Kerosene Digital. 20 July 2017. http://www.kerosene.digital/photoseries-captures-politics-pda-india/

Team Storyly. 2024. “What is Snackable Content?.” Storyly. 16 February 2024. https://www.storyly.io/glossary/snackable-content

The Quint. 2018. “Kolkata Locals Protest Against Mob That Thrashed Hugging Couple.” 2 May 2018. https://www.thequint.com/news/india/couple-thrashed-for-hugging-inside-metro-in-kolkata#read-more

***

Medhavi Gupta is a student of Sociology at the Delhi School of Economics (DSE), University of Delhi. Her other writings can be found here: https://linktr.ee/Medhavi_Gupta