Meenakshi Bharat’s Hindi Cinema and Pakistan: Screening the Idea and the Reality (published by Routledge in 2025) explores how Hindi cinema has represented, altered, and occasionally strengthened the cultural, political, and emotional ties between India and Pakistan. The representation of Pakistan in Hindi cinema is torn between two contradictory emotions – one of distrust and anger and the other of kinship and lost relations of undivided India. The idea of Indianness in Hindi cinema inevitably leads to the creation of an adversary ‘other’ – Pakistan. However, animosity is one part of the story, as the two countries also have an emotional connection. The book does not specifically address the representation of Pakistan per se but rather demonstrates how the visual text borrows from the socio-economic-political context that informs the mind of the filmmakers and shapes the popular imagination. The author has organised the book thematically, looking into the multi-faceted representation of Pakistan in Hindi cinema through different eras and genres. Pakistan in Hindi cinema is screened through the lens of war, terrorism, love, sports, and humour.

The cinematic representation of partition in Hindi cinema, the second chapter argues, beginning from V.Shantaram’s Apna Desh (1949) till Srijit Mukherjee’s Begum Jaan (2017), is etched not only in geographical spaces but also in one’s memory. The usage of Hindi words like ‘yahan’ (this side) and ‘wahan’ (that side) entered the lexicon of Partition cinema, which implied more significant connotations ranging from territorial boundaries to identifying countries through religion.

The author argues that Bollywood’s representation of Pakistan has mostly mirrored the political landscape of India. It is primarily during real events such as the Kargil War or any other military confrontation between the two countries, Hindi cinema like Border and LOC Kargil depict a valiant, selfless, patriotic Indian military that battles against the deadly Pakistani soldiers. It affirms that good has triumphed over evil.

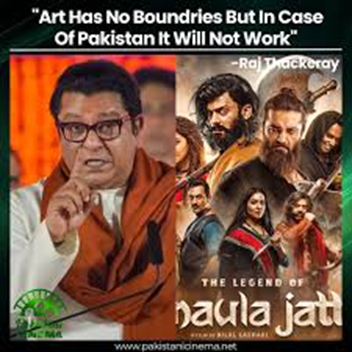

Meenakshi Bharat challenges the simple dichotomy of good versus evil by providing examples from films like Bajrangi Bhaijan (2015) and Raazi (2018) that provide a mature and complex narrative, where the protagonists from Pakistan are shown to have values and emotions that resonate with Indian audiences. The political situation in both countries, however, has created tension in the subsequent release of the films.

In addition to portraying Pakistan as a nation that incites violence, Hindi film also shows the Indian army’s conflicted involvement in the disputed region of Kashmir. The third and fourth chapters explore how Hindi cinema has re-defined terrorism and freedom (Azadi) in the context of Kashmir. While J.P. Dutta’s Border (1997) highlights the valiant contribution of the Indian Army, Mani Ratnam’s Roja (1992) alludes to state violence in Kashmir through the Armed Forces Special Provision Act. Rajkumar Santoshi’s Pukar (2000) restores the tarnished image of the armed forces by providing the message that peace-loving people can take the lives of ‘Others’ to defend their nation.

War fields take a softer pace in the genre of sports cinema. The protagonists overcome the individual crisis while playing for the country to demonstrate their patriotism. The main issue is to prove one’s allegiance towards the nation, notably for Indian Muslims, as articulated in Chak De (2007) and Gold (2018). The thrust of the fifth chapter is the shift in sports cinema where ‘goras’ (British) are held to be the common enemy who caused the nation to split. Films like Dhan Dhana Dhan GOAL (2007) and Gold (2018) exhibit a ‘deterritorialised connection’ (p.108) in diasporic contexts. Hatred is for both countries’ political leaders and governments, but love knows no boundaries. The sixth chapter examines the cross-border love between individuals who undergo rejection, betrayal, and sacrifice. In films like Raazi (2018) and Mission Majnu (2023), among others, the importance of love is subordinated to love for the country.

The book provides a nuanced approach prevalent in the representation of gender dynamics in films about Pakistan. Bharat notes that female characters frequently represent peace and reconciliation between the two nations, particularly in cross-border romance cinema. In films like Veer-Zaara and Main Hoon Na, female characters operate as metaphors for the possibility of harmony and understanding by bridging the gap between the two warring nations. Bharat contends that despite ongoing geopolitical conflicts, these depictions reveal a hidden cultural yearning for unification.

The seventh chapter examines the genre of humour, which has its mode of communication, wherein the harsh reality might appear futile or can be questioned through satire. She provides a thoughtful analysis of the factors influencing Bollywood’s treatment of Pakistan, considering everything from audience expectations to government censorship, market pressures, and changing narrative strategies. According to Bharat, Hindi cinema occasionally acts virtually as a “soft power” tool, using popular narrative to promote enmity or harmony.

Hindi Cinema and Pakistan: Screening the Idea and the Reality is a fascinating read for anybody with an interest in South Asian politics, film or cultural studies. It compels the readers to think critically about the media representation of Pakistan in Hindi cinema, which both influences and is influenced by the international relations between both countries. The book is notable for its careful and balanced exploration of Hindi cinema’s influence in shaping perceptions of a complex, often contentious relationship between India and Pakistan.

***

Pranta Pratik Patnaik is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Culture & Media Studies, Central University of Rajasthan.

Very nice review.

The recent movie: Skyforce depicts the similar plot. India is portrayed as a peace loving nation whereas Pakistan as notorious by nature.

To appease the Indian audience there are dialogues as following to fetch claps:

Pak ATC: Kaun Janab?

Akshay Kumar ( IAF Pilot over Pak aerospace): Tumhara Baap! Hindustan!

However there is some sense of professionalism shown in the movie that Pak AF pilots are not abused in the movie in the name of patriotic vibes. Opponent pilots as PoWs are also shown to be handled professionaly . Balance point of patriotism and professionalism is attempted.

Sir/Madam, How Pak cinema depicts India? What we expect is a mirror image.

Nice book and great review. Thank you so much.