Western thinkers largely dominate the writings on Sociology across academic institutions in India. On the other hand, those that address the study of human social life in India are primarily dominated by a hierarchy of one’s academic status defined by one’s identity, such as caste, race, religion and region. For a long time, there has been a debate on the question of how egalitarian Indian Sociology is, which sociologists such as Vivek Kumar and K L Sharma have discussed many times, often from opposing views[i] (EPW Engage, n.d.). On the one hand, a popular view is that frameworks in India are drawn from and influenced by Western thinkers such as Emile Durkheim, Karl Marx, Ann Oakley, Max Weber, Anthony Giddens, and Alfred Radcliffe-Brown. Or Indian thinkers like M.N. Srinivas, L.K. Ananthakrishna Iyer, G.S. Ghurye, Radhakamal Mukerjee, and D.P. Mukerji to name a few.

An important criticism of the same is the dominance of upper-caste males in the field. Indeed, much of the Indian Sociological framework is shaped by scholars who are predominantly upper-caste, elite males, as seen in the fact that Brahminical writings on caste are often cited more compared to a subaltern perspective brought to the table by thinkers like Ambedkar or C. Parvathamma, resulting in the marginalisation of lower caste voices and experiences in sociological studies. These are the crucial areas where the Western framework of the subject fails in providing an Indian context against the Western Sociology that often tends to develop universal theories, failing to accommodate India’s complex social structure of caste, religion, traditions and kinship; where such adoption may lead to oversimplified understandings or inaccurate conclusions that do not capture the essence of India’s social life[ii].

Western Sociology often prioritises themes like urbanisation, industrialisation, and class over issues like caste, untouchability, communalism and social cohesion, which are central to Indian society. For instance, caste is a defining feature of Indian social stratification, but studying through Western frameworks of race and ethnicity does not capture its intricacies. On the other hand, the scores of English texts in research often leave out texts in regional languages that provide a much broader understanding of local societies, not to mention the wider colonial legacy that is ingrained in the 108 years of Sociological curricula in Indian universities[iii]. However, a heavy reliance on the development of Indian Sociology through the Western framework and understanding, further influenced by the Caste system, has failed to adequately explain critical issues plaguing the function of Indian societies. The need for decolonising comes from escaping the shackles of Western theoretical reliance, institutional hierarchy and its validation of Indian sociological works.

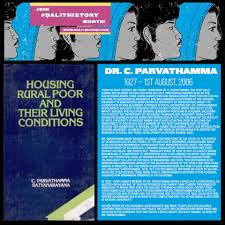

Popular subaltern views that capture the aforementioned issues in providing an ethnomethodological understanding of Indian issues and perspectives in Sociology are given by thinkers such as Prof. C. Parvathamma, the first Dalit woman Sociologist in India who won multiple awards, including the Rajyothsava Award (1990), Gargi Award (1999) and Nadoja Award (2005) for her contributions to sociological research Her scholarship included 70 research articles and 11 books. Adding to her academic contributions, she held several leadership positions in academia, including the Chair of the Department of Sociology at Mangalore University when a Postgraduate Degree in Social Work was introduced in 1977–78, the Dean of the Faculty of Arts, University of Mysore where she played a central role in building the Department of Sociology and a member of the first governing body of ICSSR besides her membership in several other committees. She retired from Mysore University in 1988 but continued her work by establishing the Centre for Research in Rural and Tribal Development in Mysore. Her works have contributed significantly to the subaltern understanding of Dalits and village societies in South India. As a Dalit and a woman, she suffered double discrimination in academia and not being able to find accommodation in Mysore after completing her PhD and becoming a lecturer at Mysore University[iv].

Her works highlight the structural inequalities ingrained in the caste system, the pervasive gender disparities, and the socio-economic challenges faced by India’s underprivileged communities, providing the lived experiences of marginalised communities in her critical works on “Housing Rural Poor and Their Living Conditions,” “Scheduled Castes at the Crossroads,” and “New Horizons and Scheduled Castes,” in understanding the intersectionality of caste, gender and society in Karnataka and at the larger context of India. In addition, Ambedkarite values and ideals of social justice and the abolition of the caste system are ideals that resonate in Parvathamma’s study into Veerasaivism as a socio-political movement, where traditional practices had given rise to the democratisation of spirituality and empowering marginalised groups, including Dalits and women projecting rise of women saints like Akka Mahadevi and on breaking the stigma of occupational hierarchy in medieval Karnataka. However, the interplay of extant political and social hierarchies has reintroduced caste distinctions.

Parvathamma’s grounded analysis covered a range of topics.: household management; traditional beliefs and practices that dictate rural norms; socio-economic challenges that affect different communities differently; rural life, local rituals; festivals; everyday practices of communities; evaluation of government intervention; policies; debate within Dalit communities on integration and autonomy. These are areas of study that often escape the universal frameworks set by Western standards. A pioneering practice of Parvathamma’s works is the projection of the interplay of public policy and Sociology as disciplines in research. Her policy recommendations have contributed significantly to the policymaking by the state government in taking corrective policy measures in the upliftment of these classes, and in essence, revitalising reformist spirits to address contemporary social issues. Combining empirical depth and a deep understanding of policy measures she contributed to the discipline. Indian universities must recognise and integrate such works into the academic curricula and decolonise academic institutions to move towards a Sociology that reflects and serves Indian society.

[i] EPW Engage. (n.d.). Is Indian Sociology Dominated by the Upper Castes? Economic & Political Weekly. https://www.epw.in/engage/discussion/indian-Sociology-dominated-upper-castes#:~:text=The%20rejoinder%20miserably%20fails%20to,not%20mentioned%20in%20the%20article.

[ii] Lele, J. K. (1981, March). Indian Sociology and Sociology in India: Some Reflexions on their Being. Sociological Bulletin. 30(1): 39-53.

[iii] Kumar, V. (2016, June 18). How Egalitarian Is Indian Sociology? Economic & Political Weekly. 51(25). https://www.epw.in/journal/2016/25/perspectives/how-egalitarian-indian-Sociology.html

[iv] Kumar, V. (2007, January 20). C Parvathamma. Economic and Political Weekly. 42(3). https://www.epw.in/journal/03/letters/c-parvathamma.html

***

Prajwal T V is a Research Scholar at the Department of International Relations, Peace and Public Policy at St Joseph’s University, Bengaluru. He is also a Course Scholar at Global Politics, School of Conflict and Security Studies, National Institute of Advanced Studies (NIAS), Bengaluru. Karamala Areesh Kumar is the Head of the Department of International Relations, Peace and Public Policy at St Joseph’s University, Bengaluru.