https://www.wendybrooks.com.au/2023/02/23/the-myth-of-the-meritocracy/

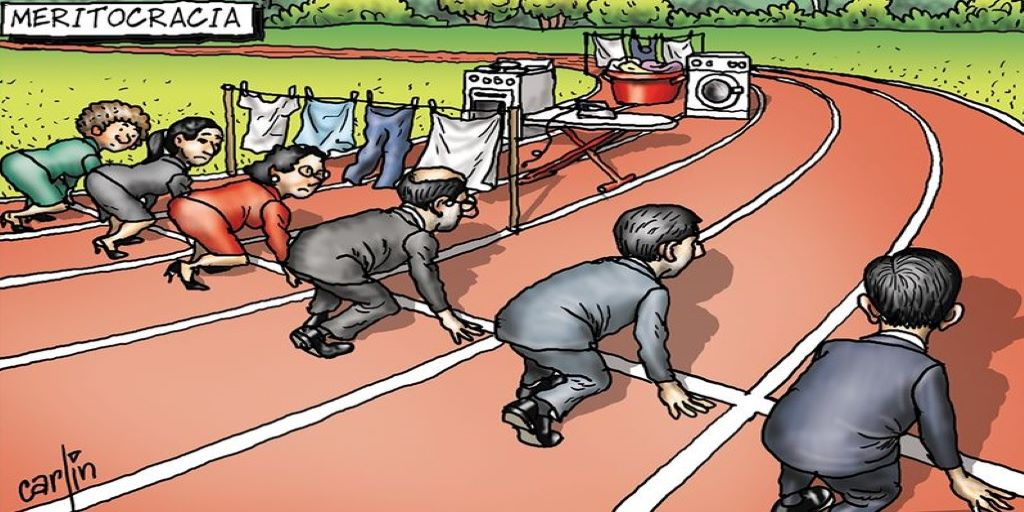

What is Merit? It is a celebrated concept, often associated with ‘talent’, a ‘achieved status.’ But is it truly achieved, or is it ascribed and inherited through the process of socialization? One of the greatest critiques of the Reservation Policy is also related to merit—namely, the claim that the reservation policy undermines the merit of an individual, which may have a harmful impact. To critically examine this idea of meritocracy in education, I will draw upon my experiences as a student at the University of Delhi.

Merit as a Construct

To examine the concept of merit, it is important to reflect on the perspectives of social scientists. For instance, Davis and Moore (1945) argue that certain coveted roles in society are critical, and the ‘talented few’ who occupy these positions must dedicate significant time, money, and energy to achieve them. Therefore, they contend that such individuals deserve differential rewards. However, critics like Tumin (1953) argue that Davis and Moore’s theory justifies existing inequalities in society, enabling the privileged to secure these coveted positions more easily. This critique resonates in the context of competitive exams in India, for instance, the Indian Institution of Technology Joint Entrance Examination (IIT JEE). Those who clear the exam and gain admission into the IITs—a top Indian institution for engineering and other higher studies—are often termed “meritorious.” However, a deeper analysis reveals that many successful candidates often hail from urban, upper-middle-class families with access to resources like coaching centres and private tutors, which confer significant advantages.

The term “merit” itself becomes problematic when we closely examine what is rewarded in competitive exams. It is often not pure intellectual ability but factors like access to preparatory resources, familiarity with test patterns, and even linguistic proficiency that determine success. Students who lack access to these advantages are frequently excluded, not because they lack talent but because they do not meet the narrowly defined criteria of “merit.”

Merit and Capital

Some argue that merit is an illusion—it is merely the accumulation of various forms of capital: social, economic, and cultural. But what transforms this accumulated capital into “merit”? I argue that the idea of merit is constructed around certain standardized behaviours or norms often established by a minority class—the elites.

A kind of standard is set by the dominant elites, which is then labelled as “merit.” Those who align with these elite standards are considered talented or meritorious. Conversely, individuals whose capital does not conform to these standards are deemed less so. For example, proficiency in the English language plays a significant role in exams. This raises questions of equity—students who lack English proficiency but possess analytical skills may still be labelled “less meritorious” due to lower scores.

The Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) Civil Services Examination provides another instance where linguistic capital disproportionately benefits certain groups. Candidates proficient in English often perform better during interviews, where subtle standards such as dressing sense, choice of words, and speaking style provide an additional edge. Marginalized communities, that lack such cultural capital, often fail to meet these implicit expectations, further perpetuating inequality.

Cultural and Social Capital in Shaping Merit

The role of cultural and social capital in shaping educational outcomes cannot be overstated. Pierre Bourdieu’s (1986) concept of cultural capital explains how certain skills, habits, and cultural knowledge are passed down from one generation to another, giving individuals from privileged backgrounds a significant advantage. For instance, students whose families value and invest in English-medium education are more likely to succeed in competitive exams where proficiency in English is implicitly rewarded.

Social capital, too, plays a critical role. Networks of influential contacts, access to mentors, and exposure to academic norms provide students from privileged families with subtle but significant advantages. These factors, while not immediately visible, have a cumulative effect on educational outcomes. Students from marginalized communities often lack these networks and are forced to navigate a system that was never designed with their realities in mind.

Economic capital further compounds these disparities. The ability to afford private coaching institutes, online resources, and high-quality preparatory material creates a stark divide between those who have the means to succeed and those who do not. For example, in cities like Kota, where coaching for IIT-JEE is a booming industry, students from affluent families are intensively trained for years, ensuring that they have a better chance of success.

Meritocracy or Inherited Privilege?

Merit, when viewed through the lens of Pierre Bourdieu’s (1977) theory of reproduction in education, serves to legitimize existing social hierarchies. Bourdieu asserts that the education system reproduces the cultural and social capital of the dominant class, presenting these inherited advantages as “merit.” Exams often reward cultural capital—fluency in the dominant language, familiarity with academic norms, or even skills like interview etiquette—cultivated through years of socialization within privileged environments.

Bourdieu’s concept of “habitus” explains this phenomenon further. Habitus refers to a set of dispositions shaped by one’s class position and upbringing, which aligns with the norms of the education system. Students from marginalized communities often find their habitus misaligned with these norms, leaving them at a disadvantage. The concept of merit, therefore, becomes a tool of symbolic violence, disguising structural inequalities as individual failures. This reinforces the existing social order, ensuring that the dominant class retains its position under the guise of meritocracy (Bourdieu, 1986).

For example, in exams like UPSC, even seemingly neutral criteria such as interview performance or language proficiency act as gatekeeping mechanisms. These criteria reward students who possess the “right” kind of cultural and linguistic capital, while those from less privileged backgrounds are excluded for failing to conform to these standards. This exclusion is not incidental but systemic, reflecting the deeply entrenched inequalities in society.

Merit, when critically examined, emerges less as an innate quality and more as a construct rooted in the accumulation of different forms of capital—social, economic, and cultural. These forms of capital are not uniformly distributed but are deeply tied to structural inequalities perpetuated by historical and socio-economic contexts. Cultural, social, and economic capital significantly shape success in academic and professional spaces, often creating an illusion of meritocracy that masks inherited privilege. Proficiency in English, familiarity with cultural norms, and access to influential networks or mentors—advantages rooted in privileged educational and social backgrounds—play a decisive role in exams like CUET PG, JEE, or UPSC. Economic capital further amplifies these benefits, enabling access to premier coaching institutes and resources. Marginalized communities, lacking such forms of capital, face exclusion not due to a lack of talent but because their resources do not align with elite-defined standards of “merit,” perpetuating social hierarchies under the guise of fairness.

References

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J.-C. (1977). Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture (Vol. 5). Sage Publications.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The Forms of Capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood Press.

Davis, K., & Moore, W. E. (1945). Some Principles of Stratification. American Sociological Review. 10(2): 242–249.

Tumin, M. M. (1953). Some Principles of Stratification: A Critical Analysis. American Sociological Review. 18(4): 387–394.

***

Sunit Singh is currently doing an MA in Sociology from the Department of Sociology, Delhi School of Economics (DSE), University of Delhi.