Gender is an organizing principle of society, historically constituted and works in intersection with other structural features of society such as caste, class, race, ethnicity, nation and region. The institution of family is deeply gendered and with the beginnings of capitalism, the gendered nature of division of labour altered. The home was rendered as a site where no production occurred and no wealth was created. The earlier idea of the household as a site of production declined in the West with production being largely conducted in major industries. The home was recast as a site of domesticity seen as natural of the ‘caring’ nature of women. Needless to say, domestic labour became invisible (Oakley) In societies such as India, the storyline was different with the household remaining not just a site for the reproduction of labour but also for production of goods and services. (Ganesh)

Both feminists and Marxist scholars have focused on the invisible nature of labour within homes on which rests the daily reproduction of labour- washing, cooking, cleaning, care for children, aged and the ill. These unrecognized labour ensures a steady stream of labour force. The wealth thus created in the capitalist societies rests on social reproduction, an essential work, extracted for free, through concealing it, under the garb of love, duty or shame. However, it is key to understand the organisation of the gendered economic activities in societies.

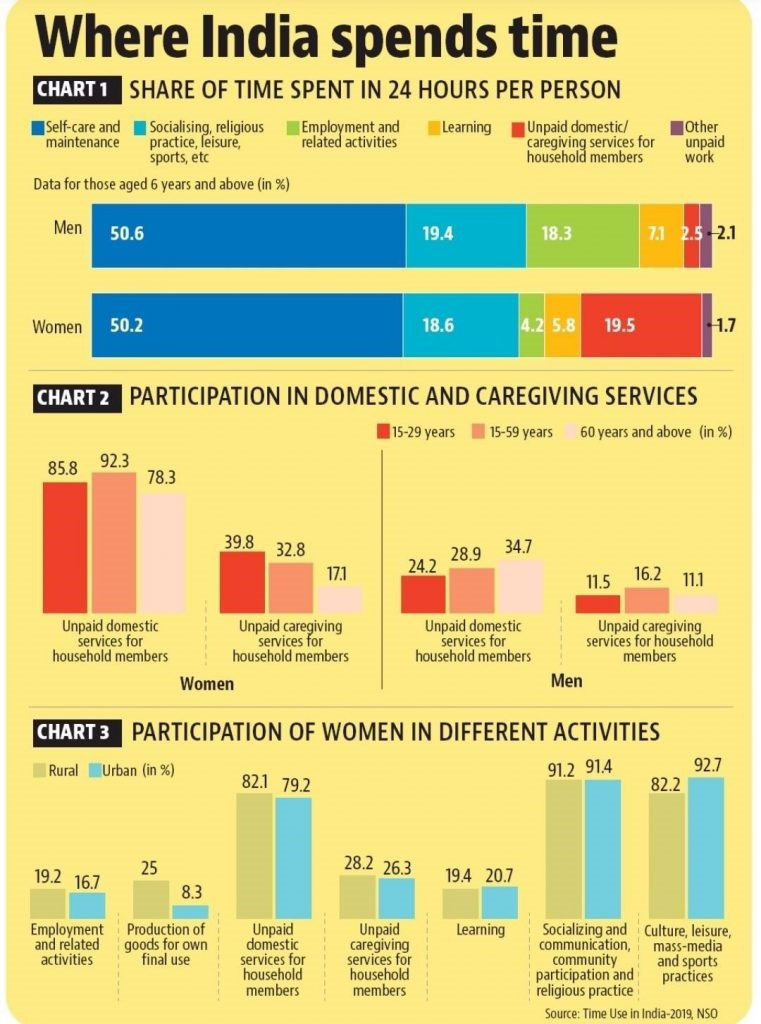

Time use surveys play an crucial role as it clearly visibilises the ‘labor’ (non-monetised labor) of women that is not attested as ‘work’ (monetised labor) by the modern economy. Time Use surveys are quantitative summaries of how individuals ‘spend’ or allocate their time over a specified time period, typically in a day. The affective vs material labor and production sphere vs social reproduction sphere complement and organise the economic and social processes. Time Use Surveys, in this sense, are critical as they provide a comprehensive measurement of all forms of work, including those outside the general production boundary.

The distinguishing factor of the Time Use Survey is that it though the unit of enumeration is a typical ‘statistical household’, the unit of analysis is on the individual basis. This is key because though household is the most disaggregated unit of both production and consumption, it is not representative unit of all needs and deprivations of its members, especially of women and children. In that sense, time use surveys highlight the extent of harmonisation that persists between family and work responsibilities for men and women. It unpacks deprivation due to the intra-household dynamics caused by the identity of either age or gender that enable or disable the distribution of power and resources within the household. In this sense as well, data production using a time use survey reduces the asymmetry that exist when household is a unit of analysis.

In India, a pilot survey of time use in six selected states was conducted in 1998-99, in addition to number of research studies on time use. Further, a national level time use survey was conducted for the first time in 2019 after which it was conducted in 2024 whose factsheet is released by MOSPI, preliminary analysis of which would be the focal point of this piece. These are definite milestones in the statistical databases for the country, despite this was a resolution taken in the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, adopted at the Fourth World Conference for Women in 1995.

The survey recorded the activities as per the International Classification of Activities for Time Use Statistics (ICATUS 2016). The data was collected for each household member aged 6 years and above with a reference period of 24 hours starting from 4 AM on the day before the date of interview to 4 AM on the day of the interview. With almost 60% of the sample from rural areas, around four and half lakh individuals were interviewed in both the survey periods. The ICATUS list of activities and the reclassification which is used for analysis that is prevalent in the literature, is given below;

| ICATUS List of Activities | Re-Classification |

| Employment and related activities | Paid Work (General Production Boundary) |

| Production of goods for own final use | |

| Unpaid domestic services for household members | Unpaid Work (Social Reproduction sphere- outside the general production boundary) |

| Unpaid caregiving services for household members | |

| Unpaid volunteer, trainee and other unpaid work | |

| Learning | Residual Activities |

| Socializing and communication, community participation and religious practice | |

| Culture, leisure, mass-media and sports practices | |

| Self-care and maintenance |

Comparative analysis of TUS 2019 and TUS 2024

Given that only the factsheet1 is released of the new TUS India 2024, analysis of the patterns observed related to two variables, participation rate and average time allocation in different activities would be solely done. This would be done for gender (male versus female) and sector (rural versus urban).

Participation rate

This statistic shows the percentage of persons performing that activity during the 24-hour reference period.

Rural v/s urban

If we compare the participation rate of persons in ‘employment and related activities’ in rural areas, we can see that there is an increase in participation rate from 37.9% in 2019 to 41.1% in 2014, an increase by almost 4 percentage points while participation rate in production for final own use has seen a negligible reduction from 22% to 21.6%. This shows that participation rate of persons in paid work in rural areas has seen an increase; In urban areas, paid work has seen an increase in participation rate in both the category of employment and related activities (from 38.9 to 40.5) and production for final use as well (from 5.8 to 6.2) between 2019 and 2024.

The pattern observed in unpaid work in the rural areas is that while domestic services to household members has seen a marginal decline from 54.6 to 54.2, participation rate for unpaid caregiving services has increased by more than five percentage points from 21.2 to 25.6 between 2019 and 2024. Whereas, for the urban areas, unpaid work including both the domestic services and caregiving services has seen a significant increase from 50.1 to 53.9 and from 19.5 to 24.5 respectively, between 2019 and 2024. Domestic services to household members include food and meals management and services, preparing and serving meals, cleaning up of house, food, garden, pet care, shopping and so on while caregiving services to household services include feeding, cleaning, medical care, passive care, playing with children and so on.

| Participation Rate in Different Activities | rural | urban | |||

| 2024 | 2019 | 2024 | 2019 | ||

| Paid | Employment and related activities | 41.1 | 37.9 | 40.5 | 38.9 |

| Production of goods for own final use | 21.6 | 22 | 6.2 | 5.8 | |

| Unpaid | Unpaid domestic services for household members | 54.2 | 54.6 | 53.9 | 50.1 |

| Unpaid caregiving services for household members | 26.5 | 21.2 | 24.5 | 19.5 | |

| Unpaid volunteer, trainee and other unpaid work | 1 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 2.3 | |

| Residual Activities | Learning | 21.7 | 21.8 | 20.7 | 22 |

| Socializing and communication, community participation and religious practice | 90.1 | 91.5 | 90.8 | 91 | |

| Culture, leisure, mass-media and sports practices | 91.8 | 84.6 | 95.8 | 92.4 | |

| Self-care and maintenance | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

Men v/s women

Between men and women, the participation rate of men in employment activities has seen an increase from 57.3 to 60.8 while production for own final use has seen a decline from 14.3 to 13% in 2024. But paid work including both employment activities (from 18.4 to 20.7) and production for own final use (from 20 to 20.7) has seen an increase in participation rate by women. As far as unpaid work is concerned, the participation rate among men has increased in domestic services for household members but has seen a decline in caregiving services but participation rate by women in both domestic services and caregiving services to household members has seen an increase.

It is significant to observe that participation rate in learning has taken a hit in both rural and urban areas. Similarly, participation rate in learning among males has seen a decline while the participation rate has seen an increase among women.

| Participation Rate in Different Activities | male | female | |||

| 2024 | 2019 | 2024 | 2019 | ||

| Paid | Employment and related activities | 60.8 | 57.3 | 20.7 | 18.4 |

| Production of goods for own final use | 13 | 14.3 | 20.7 | 20 | |

| Unpaid | Unpaid domestic services for household members | 27.1 | 26.1 | 81.5 | 81.2 |

| Unpaid caregiving services for household members | 17.9 | 14 | 34 | 27.6 | |

| Unpaid volunteer, trainee and other unpaid work | 0.9 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 2 | |

| Residual Activities | Learning | 22.6 | 23.9 | 20.2 | 19.8 |

| Socializing and communication, community participation and religious practice | 89.8 | 91.4 | 90.7 | 91.3 | |

| Culture, leisure, mass-media and sports practices | 95.3 | 88.5 | 90.7 | 85.3 | |

| Self-care and maintenance | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

Time allocation in a day (Average time spent per person per day)

This statistic shows the average time spent by a person per day in different activities primarily shows the time allocation of activities in a day with 1440 minutes. The findings suggest the following;

Rural v/s urban

It is observed that in rural areas, average minutes spent for paid activities has increased from 188 in 2019 to 198 in 2024 while for unpaid activities, the time spent has seen no change at all during the same period. Further, the increment of 10 minutes for paid activities has been possible by a corresponding decline in 10 minutes for residual activities from 1090 in 2019 to 1080 in 2024.

In the urban areas, the time allocation of activities shows that time spent on paid and unpaid activities has increased between 2019 and 2024 and therefore, the time spent on residual activities had to take a back seat. It is important to note that time spent for paid activities has increased by 10 minutes while time spent for unpaid work has increased by 6 minutes.

Men v/s women

Time Use statistics is key as it measures the time disposition by male and females on different activities. The gendered time use reflects the allocation of time between market and household and subsequently raises concerns of time poverty. It shows the distribution of time between paid, unpaid and residual activities.

It is observed from the data that the time spent by males on paid work has increased from 291 to 305 minutes between 2019 and 2024 while time spent on unpaid work has seen a decline, though negligible, from 39 to 38 minutes. This means that the time spent on residual activities has taken a cut from 1111 to 1097 minutes. Further, the time spent by females on paid work has seen an increase from 84 to 92 minutes while the time spent on unpaid work has also seen an increase from 282 to 284 minutes. Residual activities have taken a cut for females because of a corresponding increase in time spent on both unpaid and paid work.

This translates to time disposed by men in a day for paid work is 21.18% while they are spending only 2.6% of their time in the day for unpaid work; while for females, 6.3% of their time is spent on paid work while 19.7% of their time is spent on unpaid work. As mentioned above, burden of both paid and unpaid work has increased for females that has come at the cost of their leisure and self-care.

It is key to observe that men’s time disposition to paid activities is three times more than women folk while women’s time disposition for unpaid activities is seven times more men folk. This means that though time spent on leisure and self-care and maintenance has declined for both men and women, it has come at a cost for women who is rather forced to spent more on both paid and unpaid work unlike men folk for whom the time allocation on paid work has seen an increase with negligible change in men’s time disposition for unpaid work.

| Share of Time spent in Paid, Unpaid and Residual Activities | ||||||||

| 2019 | 2024 | |||||||

| Type | rural | urban | male | female | rural | urban | male | female |

| Paid | 13.06% | 13.40% | 20.21% | 5.83% | 13.75% | 14.10% | 21.18% | 6.39% |

| Unpaid | 11.25% | 10.35% | 2.71% | 19.58% | 11.25% | 10.76% | 2.64% | 19.72% |

| Residual Activities | 75.69% | 76.25% | 77.15% | 74.65% | 75.00% | 75.21% | 76.18% | 73.89% |

Insights

These statistics give us some critical insights; These numbers show the gendered nature of resource allocation, resource here being time. In addition to this, the increased participation rate in production sphere for men and women in this survey of 2024 compared to 2019, though is a positive indication of increasing work force participation rate of women, needs to be understood however, in the larger frame of neo-liberal economic policies in India. The jobless and job-loss growth witnessed in India and subsequently the stagnation in wages might have possibly forced women to enter the workforce to sustain. India has not been able to reach the pre-pandemic level of growth level with the declining demand seen in private final consumption expenditure. Therefore, this increase in participation rate and average time spent on both paid and unpaid work by women is an indication of economic injustice and hardship faced by women, which has further consequences on their food and health choices resulting in self-neglect that could possibly be due to less disposable income. The increase in participation rate and the average time spent on work, both paid and unpaid, by women leaves with less leisure time for themselves and consequently for reproducing labor power itself. This certainly is a sign of precarity, including time poverty that deprives women of discretionary time. Time poverty refers to experiencing lack of sufficient time to pursue and engage in all activities including responsibilities and other interests that contribute to one’s own wellbeing.

Another aspect that needs attention in the data presented above is the decline in the participation rate in learning. As we know, the time use is equally age differentiated and granular data on the same would provide us with clear insights. Comparative picture between TUS 2019 and TUS 2024 would not be possible at this stage. However, the declining rate in learning in both rural and urban areas and in particular among men is a sign of distress. UDISE data has consistently shown that the drop-out rate of males is higher since the secondary level of schooling, when compared to females. This in turn impacts the participation rate in higher education as well. In our context, where gender roles expect males to contribute monetarily to households as early as adolescence and females in household and domestic work given the constancy seen in the employment distribution in the country, this is not a surprise pattern seen but has not got enough attention that it requires. It is important to recognise that the resource allocation is generational (age differentiated) as well, with unequal bargaining power, given an adultist regime that dominates.

Certain caveats

It is key to understand the nuances of data collection as well. First, the data is collected through recall method which is probably the only feasible method given the Indian context but it fails to capture the intensity and vastness of work performed. Usually, dairy taking is the norm as it spells out in depth. Further, the period of survey itself could be a source of limitation. The two national level time use surveys are collected in the month of December and January, which is largely non-migration seasons. There is a possibility of increased time poverty for both young people and women during the migration season.

However, despite these caveats, the data on time use reflects the increasing time poverty that could possibly be due to increasing consumption poverty that we witness in India arising out of increasing inequalities. This resultant intensification of work calls for the state to invest in social and physical infrastructure as care economy is disproportionately run by women. This is in line with the SDG Target 5.4 that calls for the recognition, reduction and redistribution of unpaid family care work. Moreso, the necessity arises because women’s social reproductive work makes possible the creation and reproduction of workers, families, and other key entities that drive the economy and society.

1https://www.mospi.gov.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/TUS_Factsheet_25022025.pdf

***

Apurva K H works as an Assistant Professor in Government Degree College, Dharwad. Abhishek Sharma works as a researcher in Bengaluru

I just commenced 6 weeks in the past and I’ve gotten 2 check for a complete of dollar4,two hundred. This is the best decision I made in a long term. Thank you for giving me this fantastic opportunity to make extra cash from home. This extra cash has changed my lifestyles in so many approaches, for greater details visit this web page…….

.

Reading This Article:———- Tinyurl.com/4e9eczre