“We do not merely study society; we are also part of what we study.”

What does it mean to do sociology? And can we claim to do it logically? These deceptively simple questions lie at the heart of our sociological enterprise and provoke fundamental reflections about method, imagination, and epistemology. Sociology, as we are told in our early training, is not a normative discipline. It does not speak about what ought to be. Rather, it describes, analyses, and interprets what is (Weber, 1949). It focuses on the “is-ness” of social life, including its forms, flows, failures, and functions. But herein lies a paradox. To understand what is, we often have to inquire why it is that way. And that question invariably drags us toward the normative terrain, however reluctantly.

This brings us to the logicality of sociology. If it is both rational and empirical, as many claim, how does logic operate within the discipline? Is “doing sociology” merely about data collection, coding, and interpretation? Or is it also an act of philosophical engagement, containing an effort to think clearly, critically and systematically about the human condition?

I. Do We Even “Do” Sociology?

This is not just a rhetorical question. Before discussing how we do sociology, we must ask whether we do it at all. Much of sociological inquiry today, especially in classrooms and research institutes, is reduced to the reproduction of existing categories like caste, class, gender, tribe, migration, marginality, etc. These categories are indeed central to the sociological imagination. So, the problem is not with the categories themselves but with their sedimented, uncritical deployment (Connell, 2007; Chaudhuri 2003, 2022).

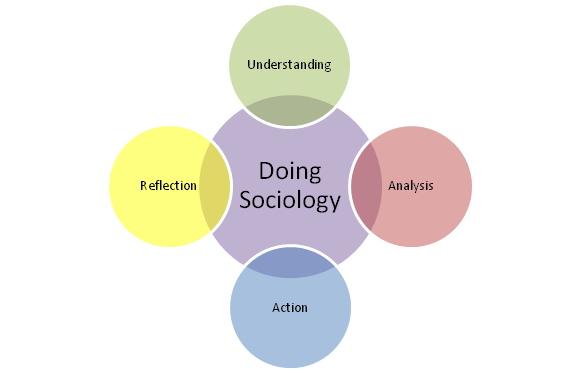

We end up repeating sociology, not doing it. To “do” sociology is to make it anew, to reinvigorate its conceptual and empirical energies, and to test its assumptions. We must ask: Is caste today only a hierarchy of birth, or has it acquired newer, market-mediated forms (Deshpande, 2011)? Is class best understood economically, or also culturally and aspirationally (Bourdieu, 1984)? These are the moves that shift us from learning sociology to doing sociology.

II. The Illogic of Logic in Numbers

Let me illustrate this further with a small example from the classroom. Kumar, a sociology teacher, has a class of thirty-five students. Out of these, two students always perform better, three remain average, and the remaining thirty are below average. What is the significant average of intellect in this class? On the surface, this may seem like a mathematical problem. One might calculate that 0.53 per cent do better, 5.63 per cent are average, and the rest are underperformers. But is this computation meaningful? Is it even sociological?

This is where logic confronts a wall. When we convert persons into percentages, we risk mutilating meaning. A sociological imagination must ask: Why are thirty students performing below average? What are the familial, linguistic, economic, or digital structures that shape their educational outcomes (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1977)? What are the unspoken hierarchies of caste, class, region or gender at play in the classroom?

Numbers are not the enemy; they are necessary. But they do not speak unless spoken for. Doing sociology logically, then, means using numbers critically, not as ends, but as entry points into deeper inquiry (Durkheim, 1895/1982).

III. Marriage, Percentages, and Cultural Specificities

Let us take another example. Marriage, one of the most pervasive social institutions, is often reduced to statistical trends: age at marriage, rates of inter-caste or inter-faith unions, decline in arranged marriages, etc. We might note that 7.8% of the population engages in a certain kind of marital pattern. But what does this “7.8%” tell us? What does it hide?

Sociology, at its best, treats such percentages not as endpoints but as provocations. What meanings do individuals assign to marriage? How does the institution of marriage embody the moral, gendered, and economic anxieties of society (Uberoi, 2006)? When we fail to ask such questions, we do not do sociology; we merely do accounting.

Thus, logic must be contextualized. Sociological logic is not the same as mathematical logic. It is not about certainty, but plausibility; not about truth, but about interpretation.

IV. Reclaiming the Logic of the Imagination

The sociological imagination, as famously defined by C. Wright Mills (1959), is the capacity to connect individual biographies with historical structures. But imagination without structure becomes fantasy, and structure without imagination becomes rigidity. “Doing sociology logically” means preserving this delicate balance.

The logic here is not about cold rationality. It is about clarity of thought, methodological honesty, and epistemological humility. It is about understanding that categories are not given; they are made. And that “society” is not a static object to be studied, but a living process to be interpreted.

In an age when data is fetishized and speed is valorized, sociology must insist on patience, nuance, and reflexivity (Bhattacharya, 2018). To do sociology logically is also to resist premature conclusions and universalising claims. It is to understand that social inquiry is not a formula; it is a craft.

References

Bhattacharya, T. (2018). Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression. Pluto Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J.-C. (1977). Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. Sage.

Chaudhuri, Maitrayee. (ed.). (2003). The Practice of Sociology. Orient Blackswan.

Chaudhuri, Maitrayee. (2022). Doing Sociology. https://doingsociology.org/2022/02/17/concepts-and-sociology-some-reflections-maitrayee-chaudhuri/

Connell, R. (2007). Southern Theory: The Global Dynamics of Knowledge in Social Science. Polity Press.

Deshpande, S. (2011). Contemporary India: A Sociological View. Penguin.

Durkheim, E. (1982). The Rules of Sociological Method (S. Lukes, ed.). Free Press. (Original work published 1895).

Mills, C. W. (1959). The Sociological Imagination. Oxford University Press.

Uberoi, P. (2006). Freedom and Destiny: Gender, Family, and Popular Culture in India. Oxford University Press.

Weber, M. (1949). The Methodology of the Social Sciences. Free Press.

***

Anil Kumar is a Professor at the Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology, Central University of Himachal Pradesh. His research interests include social theory, philosophy, sexuality, and moral questions in Indian society.

The example of better, average and underperformers is not really possible. The problem in India is that people draw illogical conclusions because they have no quantitative background.

Thank you for your engagement with my article. However, I must respectfully disagree with your assertion that the example of better, average, and underperformers “is not really possible,” and that the central issue in India is the absence of a quantitative background among people, which leads to “illogical conclusions.”

First, categorising performance into broad categories such as better, average, and underperformers is not only possible but commonly practised across disciplines, particularly in education, management, psychology, and sociology. These categories serve as heuristic devices that help us think comparatively, even when dealing with qualitative attributes. They are not intended to offer precise rankings but to encourage analytical clarity and structured reasoning. Both are central to any logical approach, whether quantitative or qualitative.

Second, sociology as a discipline emphasises the importance of context, meaning, and lived experience. It is not constrained by the quantitative–qualitative binary. Rather, it draws from both traditions to illuminate the social world. To dismiss reasoning in the absence of quantitative training is to misunderstand the depth and rigour of sociological inquiry, and to undervalue the logical sophistication embedded in qualitative methods, including comparative analysis, inductive reasoning, and grounded theory.

In fact, an over-reliance on purely quantitative approaches can itself lead to reductionism and misinterpretation if not grounded in sound sociological understanding. Logical thinking in sociology is not synonymous with statistical training. Rather, it involves:

All of these are not only possible but essential within both qualitative and mixed-methods frameworks.

Therefore, the critique that sociologists in India reach “illogical conclusions” due to a lack of quantitative training appears misplaced. The issue is not merely methodological. It is about cultivating a culture of rigorous, reflective, and responsible reasoning, which is precisely the spirit that underpins my piece of writing.

Thought provoking… Well Written. Today, Sociology is at a stage where it needs ‘rediscovery’. As you rightly point out, most of the Sociology Programs “repeat sociology”, not “do sociology”, and as a result, the field itself comes to be seen as a ‘theory-only’ kinda discipline. I think here’s where we need to have an integration of Durkheim’s positivism (as he has shown in the extensive, statistical and sociological study of suicide) and then once we have all that data, and once it has been analysed, we should go further into the “meaning of these numbers” as you rightly point out. The problem is, today, we have too much focus on “meaning” with too little data. Or vice-versa in a few other cases. We are not statisticians; we are not philosophers. We are ‘Social Scientists’ and our work is not to merely collect and analyze data as statisticians do, nor is it to merely theorize about society as many philosophers do. Our role is distinct. Our role is to produce knowledge about society, which requires the quantitative and technical rigour of the statistician as well as the logic and sharpness of the philosophical mind.

Let’s see where our discipline goes!

Well done for the article. It is well written.

Thank you very much for your encouraging words and thoughtful reflections. I appreciate your distinction between sociologists, statisticians, and philosophers. As social scientists, we inhabit a unique and demanding intellectual space that requires both methodological precision and theoretical depth.

I value your support and look forward to more such meaningful exchanges. Thank you once again for your generous feedback. Let us continue doing sociology. And do it logically, creatively, and collectively…:)