Introduction

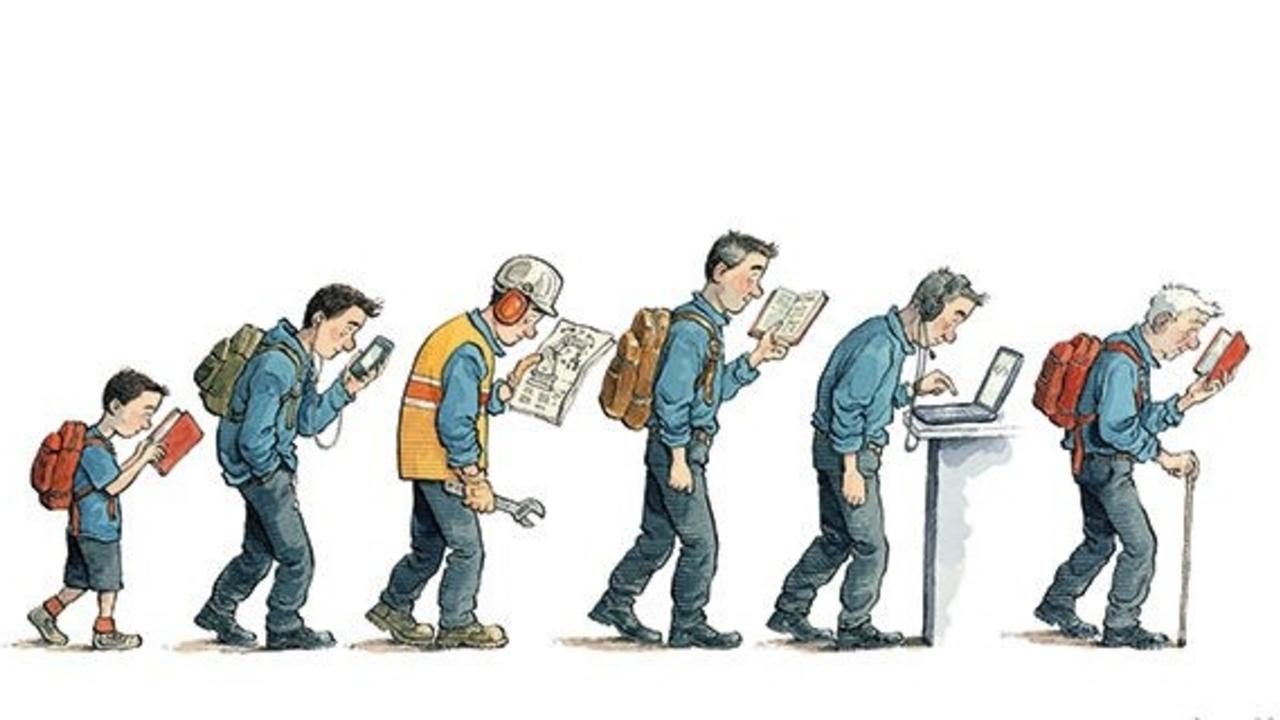

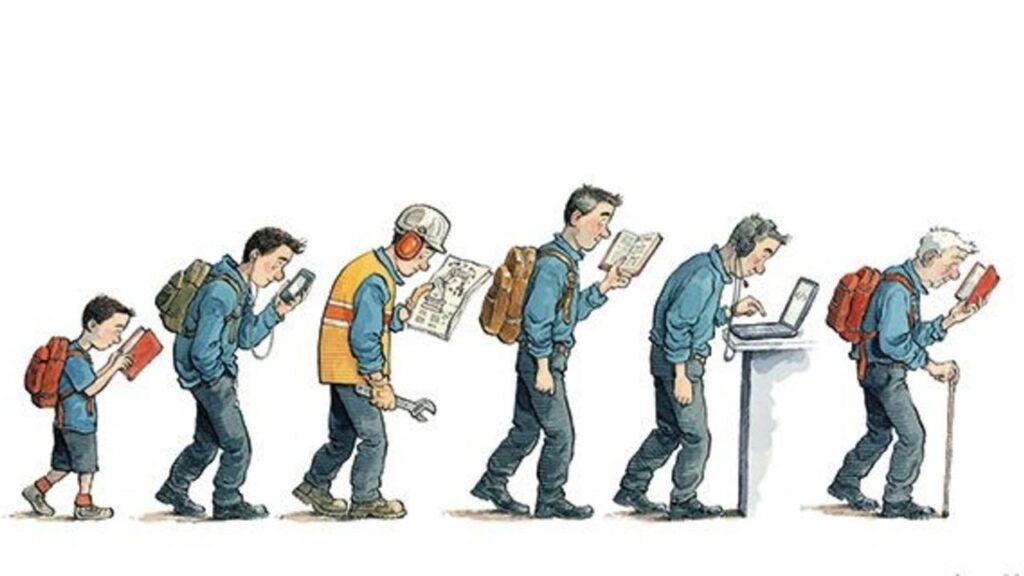

Lifelong learning (LLL) has become a buzzword of sorts in recent times. It has emerged as one of the most discussed areas in educational literature. The appearance of lifelong learning in its institutional form is a recent phenomenon. But lifelong learning notions have existed for long (Kallen, 2002). Others claim that lifelong learning has been continuing from ancient thinkers like Plato and Comenius (Withnall, 2000). Still, others claim it originated from the works of Yeaxlee, Dewey and Lindeman (Jarvis, 1995, cited in Tight, 1998).

It was however after the 1972 UNESCO report, that it started to gain limelight in academic and policy discourse. However, the focus was broad, connecting lifelong education with broader questions of equity and social transformation. The Delors Report of 1996, which influenced it, saw learning throughout life as the ‘heartbeat’ of a society. It also saw lifelong learning as a principle that rests on four pillars – learning to be, learning to know, learning to do and learning to live together – and envisaged a learning society in which everyone can learn according to their individual needs and interests, anywhere and anytime in an “unrestricted, flexible and constructive way”. [i]

Like most concepts, meanings and use change with changing economic and political contexts. The same is true of lifelong learning. The neoliberal conceptions of lifelong learning are more instrumental. The field of lifelong learning is thus stuck between the two broad frameworks that influence it; one is neoliberal, and the other is socio-cultural. In this essay, I seek to look at the two approaches.

Neo-liberalism and lifelong learning

Neoliberalism is an ideology that advocates for free-market strategies to maximise economic growth. It emphasises the maximum role of private players and the minimum role of the state in the market economy. Advocates of human capital theory of education have emphasised the role of education in increasing the productivity of the market economy. According to this theory, education is the key investment to improve the economic growth and the overall status of the people.

Increasing market specialisations and the influence of supranational organisations on the economic policies of the governments have influenced the field of lifelong learning. International corporations have started to replace the traditional organisations, like national and local bodies, to influence the social and political sphere of life (Bourn, 2001). Organisations like OECD, World Bank and European Union; countries like the US and UK have been the strongest advocates of this conceptualisation of lifelong learning (Regmi, 2015).

The role of individuals and civil society is increasing as far as lifelong learning is concerned. Lifelong ‘learning’ is being given greater importance now than lifelong ‘education’ “because it reduces the traditional preoccupation with structures and institutions and instead focuses on the individual” (Tuijnman and Boström, 2002, p 102). As the times are changing, there is a need to look at the other aspects of lifelong learning that go beyond the neoliberal tenets.

Dynamic sphere of lifelong learning

As discussed earlier, the individual is becoming the primary focus for the new framework of lifelong learning. Stephen Billett (2010) proposes lifelong learning to be considered as a ‘socio-personal process’ and a ‘personal fact’ (p 401). According to him, the process of lifelong learning is intimately connected with the individuals’ lives and works according to their interests and intentionality. There are many aspects of lifelong learning which cannot be realised through educational provisions or direct teaching alone (neoliberal and human capital models of lifelong learning assumed otherwise).

The use of new technology in today’s digital age can also significantly influence lifelong learning. Friesen and Anderson (2004) describe the three characteristics of lifelong learning as eclectic, holistic and flexible. They argue that these characteristic requirements of lifelong learning cannot be fulfilled through one single technology; however, through Semantic Web technology, which provides integrated machine-readable data on the internet, these requirements can be met easily. However, the solutions do not come without their own issues of privacy, plausibility and practicality.

A longitudinal study conducted by Gorard et al. (1999) in industrial South Wales shows patterns of educational participation of different families, especially with respect to lifelong learning. Through the study, family plays an important role in influencing the transition from compulsory to post-compulsory education. However, at the stage of post-compulsory education, many other factors influence the decisions of individuals. However, the family still continues to play a significant role at this stage and later too.

One mentions the UNESCO Report at the beginning and how the focus of lifelong learning towards human rights, social inequality and social justice started with the release of two very important reports by UNESCO: Faure Report, 1972 and Delors Report, 1996. This was the beginning of the humanistic model of lifelong learning (Regmi, 2015). This view of lifelong learning is at odds with the instrumental approach of learning, which primarily focuses on economic advancement and competency.

Provisions of lifelong learning in India

Immediately after the independence, the main focus of education was on completing the task of providing literacy to the population so that the other programmes of national development are accelerated. Therefore, most of the education policies, including adult education (lifelong learning had not been conceptualised in Indian setting then), were formulated to support the enhancement of literacy in the country. “The liquidation of mass illiteracy is necessary not only for promoting participation in the working of democratic institutions and for accelerating programmes of production, especially in agriculture, but for quickening the tempo of national development in general” (NPE, 1968, p 7).

NPE-1986 recognises the importance of adult education and adult literacy as instruments of liberation (from ignorance and oppression). It also talked about establishing adult education centres in specific areas inhabited by scheduled tribes and scheduled castes. Hence, the policy tried to widen the scope of adult education as compared to the earlier policy.

NEP-2020 has further widened the scope of adult education, going much beyond mere literacy. First of all, it has listed out some abilities such as filling out forms for banking transactions, reading government circulars, being aware of one’s basic rights, etc., in an illustrative list of outcomes it plans to achieve in the near future. Second, it proposes a six-pronged strategy to expedite and institutionalise adult education and lifelong learning.

It has been argued that by adopting the new paradigm of LLL, which is primarily driven by “market-centric neoliberal principles, Indian adult education has lost its core and traditional learning ecology” as there is “a gradual submission to the pursuit of global economic competitiveness”. [ii]

Conclusion

Lifelong learning is stuck between the two broad frameworks that influence it; one is neoliberal, and the other is socio-cultural. The key findings suggest that the notions of neoliberal economy and globalisation are still potentially strong to influence the provisions of lifelong learning in a significant manner. However, others believe in a more dynamic form of lifelong learning getting shaped by various factors like culture, community, society, technology etc. These two viewpoints resemble the eternal struggle between capitalism and socialism, between the neo-liberal ideology of the state and the ideology of the welfare state, between individualism and communitarianism. The presence of this dichotomy in India also suggests that lifelong learning cannot be kept aloof of the forces of the economy and society.

References:

Bourn, D. (2001). Global perspectives in lifelong learning. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 6(3), 325-338.

Faure, E. et al. (1972). Learning to be: the world of education today and tomorrow. Paris: UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000223222. (July 17, 2021).

Friesen, N., & Anderson, T. (2004). Interaction for lifelong learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 35(6), 679-687.

Gorard, S., Rees, G., & Fevre, R. (1999). Patterns of participation in lifelong learning: Do families make a difference?. British educational research journal, 25(4), 517-532.

Jarvis, P. (1995) Adult and Continuing Education: theory and practice (London, Routledge, second edition).

Kallen, D. (2002) Lifelong Learning Revisited, in: D. ISTANCE, H. G. SCHUETZE & T. SCHULLER (Eds) International Perspectives on Lifelong learning: from recurrent education to the knowledge society (Buckingham, Open University Press).

Ministry of Education. (1968). National Policy on Education. Government of India.

Ministry of Human Resource and Development. (1986). National Policy on Education. Government of India.

Ministry of Human Resource and Development. (2020). National Education Policy. Government of India.

Regmi, K. D. (2015). Lifelong learning: Foundational models, underlying assumptions and critiques. International Review of Education, 61(2), 133-151.

Tuijnman, A., & Boström, A. K. (2002). Changing notions of lifelong education and lifelong learning. International review of education, 48(1), 93-110.

Withnall, A. (2000) Older Learners – Issues and Perspectives, Working Papers of the Global Colloquium on Supporting Lifelong Learning (Milton Keynes, Open University).

[i] https://uil.unesco.org/fileadmin/keydocuments/LifelongLearning/en/UNESCOTechNotesLLL.pdf, accessed on 21st August 2021.

[ii] https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1234807.pdf, accessed on 21st August 2021.

**********

Diwakar Soni is an MPhil research scholar in National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration (NIEPA), New Delhi.