“Apes, too, have organs that can grasp, but they do not have hands.”

Martin Heidegger, What Is Called Thinking?

“The Hindu would prefer to be inhuman rather than touch an untouchable.”

Bhimrao Ambedkar, Untouchables or the Children of India’s Ghetto

There is a village called Somnath that is located in the Chandrapur district of Maharashtra which is well-known for its rehabilitation programme for leprosy afflicted patients. As someone who was born and brought up in the Chandrapur district, I have had the opportunity to visit Somnath as well as Anandwan, the settlement near Warora where Baba Amte had first established the Maharogi Sewa Samiti for curing and rehabilitating leprosy patients.

The disease of leprosy has had an extremely stigmatized history in India. Its bodily consequences involving physical disfigurement puts its sufferers in the position of terrible medical and social stigma. Although India has declared itself to be leprosy-free in 2005, it continues to account for more than half of new cases of leprosy reported worldwide.[1] As it was considered to be a nearly incurable disease, the British government had introduced the infamous and draconian Indian Lepers Act in 1898 which allowed for the segregation of leprosy patients away from the main cities and villages. This act, which is now repealed, is noteworthy for showcasing the social contempt directed towards leprosy patients in colonial India that were legally enforced by British law.[2]

The intensity of social contempt directed at persons afflicted with leprosy owed its origins to the belief that this disease is highly contagious or infectious and is transmitted through touch. The bodily deformity or disfigurement that is the consequence of this disease only added to the element of social stigma faced by leprosy patients. This disease was later found to be curable and not nearly as contagious as it was earlier believed. While it was believed that even casual contact with a leprosy patient is enough for its transmission, medical research found out that this disease could be transmitted to someone else only through sustained and long-term contact with an untreated patient.[3] Despite such research findings, leprosy patients have had to face intense social stigma in India from their immediate family members to the medical fraternity at large. This is something that Amte, a medical doctor himself, wished to solve by establishing several rehabilitation settlements for leprosy patients in Vidarbha, Maharashtra.

When I was in Somnath in 2015, I had the opportunity to speak to several survivors of leprosy. Everyone I spoke to had a story about how they were ousted from their own homes after their families and village community suspected that they had contracted leprosy. They had extremely heart-wrenching details to share about where they somehow survived in nearly homeless conditions before they were informed about Amte’s project of rehabilitation. The survivors I spoke with were all engaged in “manual” work – pottery, sculpting, farming, handicrafts, cooking, masonry, hand-looming, carpentry, etc. Even after surviving leprosy, their hands had nonetheless sustained deep physical disfigurement, with most of their fingers either having become stiff or stunted.

My conversations with leprosy survivors in Somnath revealed how much they related their bodily disability with their newfound dignity and respect in labouring with their hands. Such narratives also detailed how this dignity and respect were denied to them as they were socially shunned earlier, with them finding it nearly impossible to find some shelter or food, leave alone stable employment. One such narrative is distinctly etched in my mind, where a leprosy survivor told me, “We live with self-respect now. Earlier, we were treated like untouchables” (Aamhi aata sanmanane jagto. Pahile loka aamchya sobat asprushyansarkha vagayche).

I remember this statement very distinctly because of the comparison of leprosy with untouchability, where the leprosy survivor likened their condition to that of facing the same kind of stigmatized and discriminatory treatment that caste-Hindu society shows towards the untouchables. What I also found noteworthy in this statement was the peculiar element of being witness to the exclusion of untouchables, which the person found as being similar to their social segregation after contracting leprosy. One may count several reasons why this comparison made reasonable sense to them – the element of similarity in stigma, exclusion, and discrimination must have made them bring up this comparison of leprosy with untouchability. However, I did notice then that such a comparison would have been very unlikely to occur in the mind of someone untouchable by birth. And this is precisely something that was the subject of what troubled me after this conversation – the popular meanings of untouchability in our society that lends its usages to various kinds of sufferers towards making comparative allusions to “being treated like” untouchables. What does it mean to be treated like an untouchable when you are, in fact, not an untouchable by birth?

Some years later, I was struck by a sentence occurring in Babasaheb Ambedkar’s 1945 book What Congress and Gandhi Have Done to the Untouchables. This sentence was an exact inversion of what I had heard from the leprosy survivor in Somnath, and it read, “[t]he [Hindu] religion to which they [untouchables] are tied, instead of providing for them an honourable place, brands them as lepers, not fit for ordinary intercourse.”[4] Ambedkar was utilizing the horror and stigma attached to the disease of leprosy in colonial India to depict the miserable condition of the untouchables. And here too, the element of comparison provoked several questions in my mind. What does it mean to be treated like a leper when you are, in fact, not suffering from leprosy? Ambedkar highlights the element of exclusion from ordinary social intercourse here as the justification for making this comparison between leprosy and untouchability.

Crucially, leprosy was considered to be infectious or contagious at the time when Ambedkar was writing, and the element of literal not-touching and not-sharing proximate spaces with leprosy sufferers by society at large must certainly have been in Ambedkar’s mind when he made this particular comparison. There is a lot to be said about a possible history of entanglement between the medical condition of leprosy in a caste-based social structure that is always already determined by the practices of untouchability, thus implying a medicalized hyper-sensitivity towards notions of not-touching, social distance, segregation, ex-communication, quarantine, humiliation, exclusion, etc. The question of this vexed historical relationship lingered in my mind ever since I came across the comparison between lepers and untouchables in Ambedkar’s text.

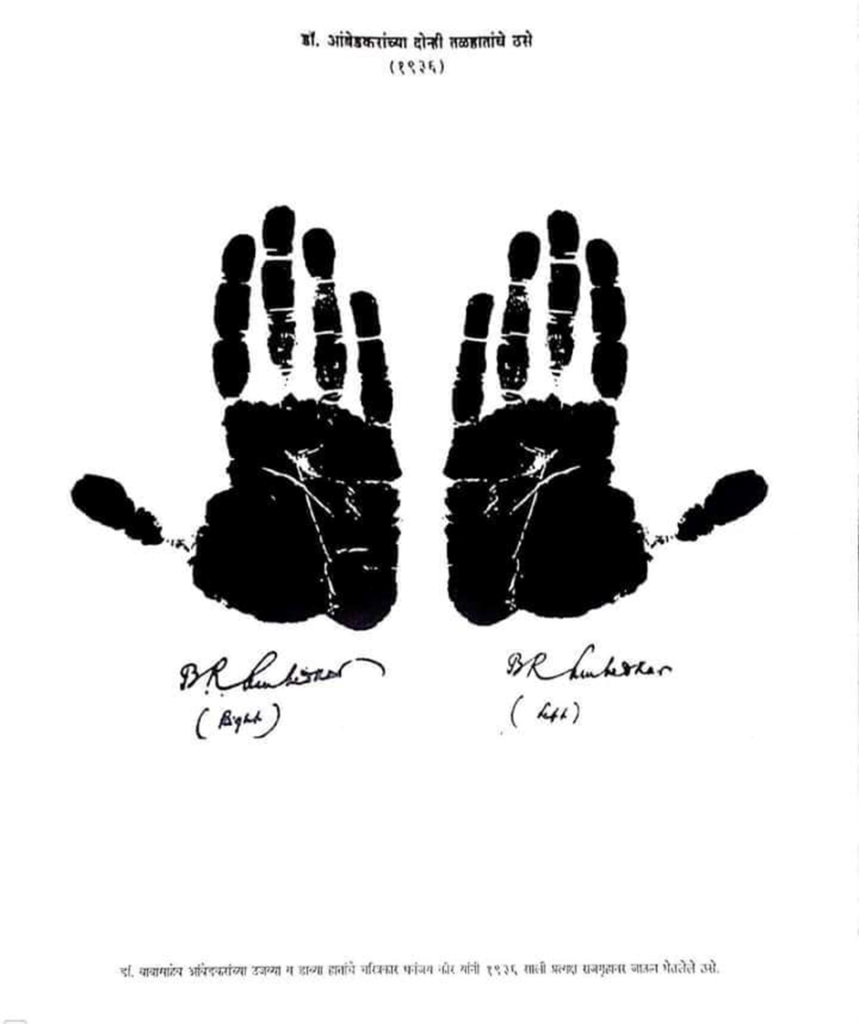

The substance of this question came back to me recently when I came across the following image of the impressions of Ambedkar’s hands. No details could be found about the source or possible reasons for why Ambedkar got made such an impressionistic image of his hands. However, the image of his hands certainly made me remember the hands of the leprosy survivors, given that I could not stop thinking about that one comparison made by Ambedkar.

[Image 2: Front impressions of Ambedkar’s hands as taken by his biographer Dhananjay Keer in 1936. Source: https://www.brambedkar.in/impressions-of-both-the-palms-of-babashaheb-ambedkar-1936/]

At the risk of some speculation, I wondered what is the relationship between the hands of an untouchable and the hands of a leper? Following the leprosy survivor’s and Ambedkar’s metaphorical substitution between the leper and the untouchable, we can point out that there are indeed very discernable physical differences between the hands of a leper and an untouchable. An untouchable’s hands may not suffer from a physical ailment or a disfigurement, and yet an untouchable’s hands, like a leper’s hands, have historically represented a moral menace in the minds of our caste-Hindu society at large.[5] Experiences from Ambedkar’s own life, as they are recorded in his autobiographical fragment “Waiting for a Visa”, reveal the instance where he was barred from drinking water at his school because the touch of his hands was polluting the common water tap. He had to wait for the school peon to open the tap for him every time he felt thirsty in his school.[6]

Maybe Ambedkar wanted to record the sheer innocuousness of an untouchable’s hands for posterity so that those who come after him would be forced to think about what was it about these hands that they were subjected to the cruel practice of untouchability? Hands that labour, manufacture, and write; hands that cook, serve, and feed; hands that give, receive, and embrace – are turned into hands that are feared, shunned, and jabbed away in a society that is maniacally overrun by the notion of untouchability. How can an analysis of untouchability be complete without first investigating what (and whose) hands can or cannot do something in Hindu society?

Martin Heidegger provocatively wrote that animals do possess organs that can hold, grip, and stretch, but they do not essentially have hands.[7] According to Heidegger, only human beings have hands, and hands are what separates humans from animals in their most essential species-related difference. From an anthropological standpoint, it might be true that all human beings have hands. However, from a sociological or a historical standpoint, the disease of leprosy and the practice of untouchability reveal to us that all human beings may not have the same kinds of hands and that all hands are not equal.

Ambedkar had forcefully written that a Hindu would prefer to be inhuman rather than take the risk of touching an untouchable.[8] It is within the notion of inhumanity itself that one can locate the problem of the caste Hindu hands that are involved in the practice of untouchability. And perhaps, it is in pointing toward the very irreducibility of being an equal human person that explains why Ambedkar got an impression made of his hands.

[1] https://www.business-standard.com/article/news-ani/india-accounts-for-over-half-of-world-s-new-leprosy-patients-shows-data-122013000422_1.html

[2] https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/long-after-lepers-act-is-gone-discrimination-still-stays-on-statute/article4375544.ece

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/healthcare-network/gallery/2016/nov/23/leprosy-disease-of-past-in-pictures-vaccine

[4] B.R. Ambedkar, “What Congress and Gandhi Have Done to the Untouchables”, In Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings and Speeches Vol. 9, edited by Vasant Moon, Mumbai: Government of Maharashtra, 1991, p. 312.

[5] Gopal Guru, “Caste”, In The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology, edited by Hilary Callan, London: Wiley, 2018.

[6] B.R. Ambedkar, “Waiting for a Visa”, In Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings and Speeches Vol. 12, edited by Vasant Moon, Mumbai: Government of Maharashtra, 1993, p. 671.

[7] Martin Heidegger, What Is Called Thinking?, translated by Fred D. Wieck and J. Glenn Gray, New York: Harper & Row, 1968, p. 16.

[8] B.R. Ambedkar, “Untouchables or the Children of India’s Ghetto”, In Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings and Speeches Vol. 5, edited by Vasant Moon, Mumbai: Government of Maharashtra, p. 29.

***

Ankit Kawade is a PhD student at the Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi. His monograph titled The Genius of the Chandala and the Gospel of the Superman: Nietzsche, Ambedkar, and the Conflict of Interpretations is under contract and forthcoming with Navayana.