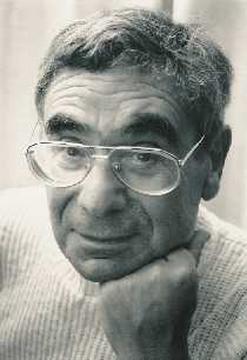

Basil Bernstein has perhaps been one of the most important figures in the sociology of education and knowledge. His works on schooling, language and family have been foundational to the understanding of differential achievements in education. However, in the understanding of contemporary issues in knowledge production, education and social structure, the application of Bernstein’s theoretical frameworks are relatively limited. One of the reasons cited by some writers is that Bernstein’s theoretical models have often been misunderstood[i] or critiqued as impenetrable and inapplicable.[ii]

In the introductory chapter of his collected works, Bernstein himself acknowledges this misunderstanding of his work and expresses a sense of unease at publishing a set of ideas that for him were constantly developing.[iii] It, therefore, helps to approach his concepts perhaps from his perspective of tentativeness and less surety and to see his models for what they are —constantly evolving theoretical devices that can perhaps help us make sense of certain aspects of social reality; to guide our sociological imagination to fundamental questions; one of them being how the underlying structures and principles of social institutions shape collective experience.

Biography and Social History: A Brief Look at Bernstein’s Intellectual Foundations

Bernstein’s biography provides valuable hints into his persistent interest in the same set of themes throughout his academic career. After the Second World War, Bernstein worked at the Bernhard Baron Settlement[iv] involved in family casework and running boys’ clubs which deepened his lifelong interest in class structures and processes of cultural transmission of values and of knowledge, which he observed in the Settlement. In 1947, he was accepted to the London School of Economics where his interest in sociology peaked with exposure to debates between functional and conflict approaches. He was in particular deeply impacted by Durkheim, and Durkheim’s focus on ‘the social bond and the structuring of experience’[v] which is visible, especially in the collection of papers titled Class, Codes and Control, the third volume of which focuses on the transmission of educational knowledge.

Even as Bernstein was emerging among a group of British sociologists focusing on class inequalities and education, his approach was different given his orientation towards French structuralism focusing on discovering underlying structures of social phenomena and it is here that his influences from Durkheim can be noted the most. Even as his work primarily relates to the understanding of underlying structures to social phenomena Bernstein’s intellectual roots draw primarily from the Durkheimian tradition. His work may be focused on schooling, socialization and language but they draw heavily from the themes of ritualisation, social control, and essentially understanding the ‘moral basis’ of a social institution. This is most visible in his concerns with ‘the changes in the moral order of the schools as institutions and as transmitters of systems of meaning, value and instrumentality’[vi].

On the Social Structuring of Knowledge

Bernstein’s concern with order and structure led him to develop an interesting set of concepts and theoretical models to analyse educational knowledge. One text in particular that brings together several of his concepts is the 1971 paper ‘On Classification and Framing of Educational Knowledge’. In this paper, Bernstein offers a model of the classification of educational knowledge but its larger function is to help one understand how the classification and distribution of knowledge reflect principles of social control. Bernstein develops his concept of the curriculum in this paper and distinguishes between two types of curriculum: closed and open. The specific form of these two curriculum types is characterised by two distinct sets of principles, which he terms the collection code and the integration code, respectively. Before elaborating on the types of codes, it is important to understand two other concepts that determine the code type: the concepts of classification and framing.

Bernstein uses the concept of classification to explain how the contents of a curriculum are structured; the degree of insulation and rigidity of boundaries between contents of the curriculum that can determine the form of the educational code of the system. Thus strong boundaries between subjects signify a collection code, whereas relatively blurred boundaries between subjects signify an integrated code.

The concept of the frame refers to the context in which knowledge is transmitted; in other words, the frame is the underlying principle of the pedagogical system; it refers to the nature of the boundaries within which what knowledge may or may not be transmitted is determined. Thus, strong frames or strong boundaries shaping the nature of the pedagogical relationship between the teacher and student may offer greater control to the teacher over what is transmitted as knowledge to the student. This strong framing of the pedagogical relationship is again a characteristic of the collection code.

To give an illustration of the classification and framing within the collection code, Bernstein draws attention to the English and European education systems. He looks at the English educational model as an example of a strong classification of the curriculum with strong insulation between subjects and each specialisation having a certain status and social significance. In the collection code subject, loyalty is developed early in the student as part of the socialisation process in educational systems. With age, more clear-cut boundaries and specialisations emerge between subject domains, which lead to the creation of specific educational identities and experiences.

Bernstein argues that this process of socialisation into differentiated knowledge is reflective of socialisation into social order; it is only after a long period of successful socialisation into a subject, and for a small fraction of learners that the ‘ultimate mystery of knowledge’ of the understanding that ultimately knowledge is permeable and the ordering of knowledge provisional is revealed. Although Bernstein does not provide an example of this group, one could perhaps think of highly specialised knowledge at the level of university research, which is made accessible to the learner only after a very long period of association with and specialisation in a specific subject.

Bernstein looks at the pedagogical framing in the European education system also as a model of the collection code. Bernstein characterises the European model as one with strong pedagogical framing; this means that the boundaries of what is to be taught as valid knowledge are rigid and the student is expected to accept the given selection and organisation, pacing and timing of knowledge within the pedagogical framework. Bernstein observes that within a collection code focused on strong framing, ‘the evaluative system emphasizes attaining states of knowledge rather than ways of knowing’[vii]. The strength of the frame and the fixed nature of boundaries imply that the educational relationship would also tend to be more hierarchical and ritualised with the learners having little status and rights.

Bernstein also gives an interesting perspective on the effects of classification and framing on the relationship between knowledge received in school and knowledge received in the private sphere through the family, peers and community. Within collection codes socialisation focuses on discouraging the connection between educational knowledge and the learners’ everyday realities. This Bernstein argues makes educational knowledge esoteric and confers special social status and significance to those who possess it.

Knowledge and the Moral Order: Circling Back to Durkheim

The integrated code was for Bernstein more theoretical and he saw very few empirical examples of institutions experimenting with a shift from the closure and rigid boundaries of the collection code. Theoretically, integration codes are characterised by much less insulation between curriculum contents, relatively more relaxed framing of the pedagogical relationship and possibly more autonomy and discretion for the student. The open relationship between subjects implies a shift toward a focus on early understanding of the deeper structures of the subjects; towards a focus on ways of knowing rather than achieving states of knowledge. This shift in classification and framing in integration codes also has implications for change in existing authority structures and the specificity of educational identities.

Bernstein also argues that in the collection code, the organisational structure of the school is characterised by vertical relationships between senior and junior staff, with more interaction within departments and isolation from other departments. In the integrated code on the other hand, because of the openness of the content boundaries and the de-emphasis on specialisation, subjects enter into a social relationship requiring more cooperation towards a common purpose—focusing on how knowledge is created and what are the ways of knowing. Relationships between teachers and senior and junior staff may also be more horizontal.

Bernstein finally comes back to the question of order and its creation through different forms of the education code. The collection code and its characteristic classification of knowledge and framing of pedagogical relationships are premised on differentiation and hierarchy. It is interesting to see how Bernstein, inspired by Durkheim locates the moral and religious purpose of education as a social institution. He suggests that in these systems of educational knowledge premised on the collection code, for those who can go beyond the ‘novitiate’ stage the collection code can provide order, commitment and identity. He however also argues that ‘for those who do not pass beyond this stage, it can sometimes be wounding and be seen as meaningless.’[viii] The integrated codes too can pose certain problems to the question of order. Even as integrated codes provide the possibility of less hierarchical relationships and more autonomy for the learner, Bernstein states that they could also be at risk of producing a culture without a sense of explicit purpose for the learner. For integration codes to function, Bernstein states that there must be a high ideological consensus amongst its practitioners and teachers would have to be highly trained in handling ambiguity at the level of both the curriculum and in the social relationships formed with students and with other teachers.

Theoretical Frameworks: Rigid Models or Flexible Tools for Sociological Imagination?

As students of sociological research, it can often be daunting to read sociological theory; theories are written in a completely different time and space and can be challenging to apply in contemporary, local contexts. But theoretical frameworks can be instrumental in furthering our understanding of specific phenomena. For example, in the Indian education policy landscape, there has been much conversation on making formal education more student-centred, and the problem of rote learning, disconnect between the content of the textbook and the student’s lived reality have been highlighted repeatedly in policy discourse. It is here perhaps that one may find Bernstein’s model of classification and framing of educational knowledge useful to uncover underlying principles of social order, control and authority structures that shape key relationships of curriculum, pedagogy and evaluation in the Indian education system.

The purpose of using theoretical models then is not to impose a model without taking into account the specific historical and sociological circumstances under which the Indian education system has evolved. The important lesson perhaps to be drawn from Bernstein’s work is that theoretical models are developed to help us make sense of reality, not necessarily replicate its exact empirical form but to help us unpack some of the features of reality, throwing light on selected aspects. In this sense, theoretical models are not meant to be perfect; they are constantly worked upon and are always evolving, the more they are applied to empirical reality. In a certain way, Bernstein’s work helps the student of sociology to perhaps sit a little more comfortably with tentativeness, a principle that lies at the foundation of all research.

[i] Sadovnik, A. (2001). Basil Bernstein (1924-2000). Prospects: The Quarterly Review of Comparative Education, 31(4): 687-703.

[ii] Singh, P. (2002). Pedagogising Knowledge: Bernstein’s Theory of the Pedagogic Device. British Journal of the Sociology of Education, 23(4): 571-582.

[iii] Bernstein, B. (2003) Class, Codes and Control: Theoretical Studies Towards a Sociology of Langauge. Volume I. London: Routledge. Originally published in 1971:2.

[iv] An educational institution in London’s East End established among the Jewish settlement covering students from the primary level to adult learners.

[v] Bernstein, B. (2003) Class, Codes and Control: Theoretical Studies Towards a Sociology of Langauge. Volume I. London: Routledge. Originally published in 1971:2.

[vi] Atkinson, P. (1985). Language, Structure and Reproduction: An Introduction to the Sociology of Basil Bernstein. London: Methuen: 2.

[vii] Bernstein, B. (2003) Class, Codes and Control: Towards a Theory of Educational Transmission. Volume III. London: Routledge. Originally published in 1975:89.

[viii] Bernstein, B. (2003) Class, Codes and Control: Towards a Theory of Educational Transmission. Volume III. London: Routledge. Originally published in 1975:91.

***

Roma Bhattacharya has submitted her PhD at the Centre for the Study of Social Systems (CSSS), School of Social Sciences (SSS), Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). Her research interests include educational policy, curriculum studies and science studies.