Link to the editorial note and the panel discussion can be found here.

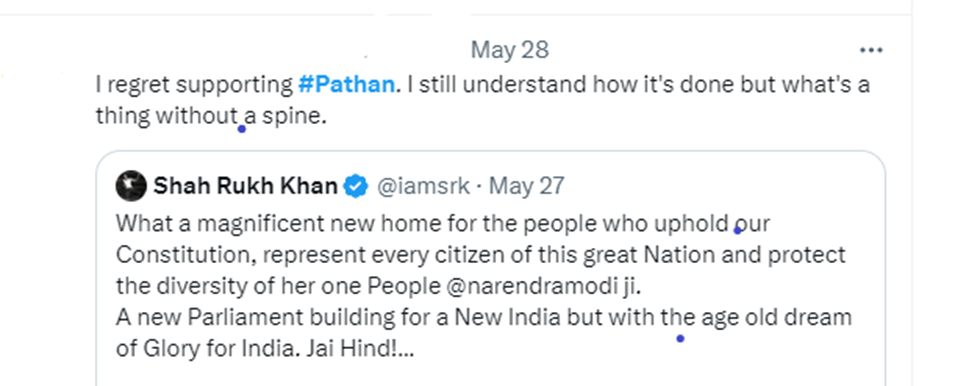

“ I regret supporting Pathan. I still understand how it’s done but what’s a thing without a spine”

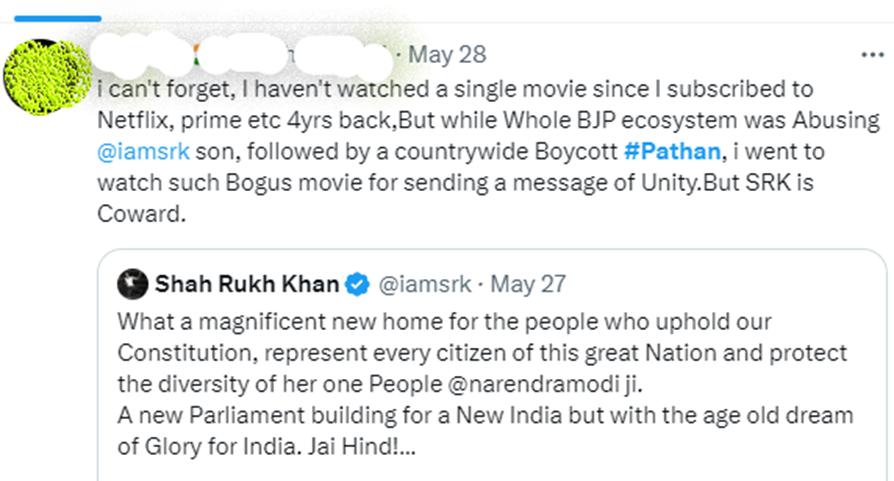

I can’t forget I haven’t watched a single movie since I subscribed to Netflix, Prime 4 years back. But while the whole BJP ecosystem was Abusing @iamsrkson , followed by a countrywide boycott #Pathan, I went to watch such Bogus movie for sensing a message of Unity. But SRK is coward”

“ Now liberals who called # Pathan a hit ,Will no call it a flop”

The above tweets express a range of responses, from very different ends of the political spectrum and get to the heart of the matter around Shahrukh Khan’s fandom. They help us capture the affective complexions of Shahrukh Khan’s fan constituency. Reading the surfeit of exhilarated fan comments on Twitter and other social media upon the release of Pathaan and the recent fan response to Shahrukh Khan’s tweet congratulating the Modi government on the new parliament building, one can discern the arrival of a moment in Hindi cinema where cinema’s relationship to politics came to sharp relief. [i]The frenzied activities of fans around the globe surrounding Pathaan were indexed beyond the text of Pathaan. For some, Pathaan seems to be a text of patriotism and a parable of traditional secularism, whereas for others it is a text that parallels the star’s own offscreen and on-screen challenges. Pathaan in these readings is at times a complex portrait of Shahrukh Khan’s star persona and at others a spy thriller Indeed, it is often both at once, as each of the two makes significant strides into both these realms of narration. These compounding interpretations are legitimate and provocative but not entirely explanatory of the fantastical realms that the film seems to have opened up and the euphoria generated globally.[ii] In all the density of interpretations around Pathaan, what we cannot fail to observe is how it marks a significant shift in the star-fan relationship in Hindi Cinema. Through the connected nodes of the text, the star and the fan Pathaan transitioned from a much-anticipated film to a global event.

How might we place Pathaan in the crisis of Hindi cinema? Is it productive to stay longer with the fan frenzy and political statements to understand the present of Hindi cinema? Is cinema, consequential to politics? Jogging our memory of Indian film history provides some thumbnail sketches of how we can approach and apprehend these relations. Political establishments and parties have always drawn extensively from the surplus of popular cinema and the star system. This nexus between cinema and politics is frequently understood as drawing the charisma of the stars into politics. Examples of this model can be found in the political careers of Nargis Dutt, Sunil Dutt, Raj Babbar, Jaya Bachchan, Hema Malini, Jayaprada, Shatrughan Sinha, and many others who participated in electoral politics. This model has worked in the South Indian states, Bhojpuri and several other film industries as well. What we see in the South Indian film industry ( Tamil, Telugu and Kannada specifically) is a different model of cinema and politics where the Stars, MG Ramachandran, N T Rama Rao, Jayalalitha, and others have formed parties and wielded enormous political power. Rajkumar, the Kannada superstar, held immense political power despite not creating a political party.[iii] He had a stake in electoral politics by influencing the political opinions of his fans. The hyperbole of the fan is constituted through a myriad range of activities, from devotion and defiance to staking claims and negotiating politics around the star body. Fandom, with its contingent and inconsistent responses, affective performances and immeasurable nature display a certain unwieldiness as an analytical category. Yet, it is the fan-star relationship which we must turn to now to discern the nature of the relationship between cinema and politics.

Although fan cultures around major Bollywood stars have always existed, substantial scholarship on such formations has yet to exist. Shrayana Bhattacharya’s chronicle of Shahrukh Khan’s young female fans and Shohini Ghosh’s work on Salman Khan’s stardom are exceptions to this. Bhattacharya, who followed informal fan clubs of the star for over a decade, effectively invoked Sharukh Khan as a device to explore questions of gender, sexuality, masculinity, and economic aspirations. Bhattacharya reads Sharukh Khan’s female fan base in the framework of a new class of young women seeking fantastical intimacies engendered by the shifting landscapes of emotional precarity in neo-liberal India. Shahrukh Khan’s stardom spanning three decades has distinct figurations in- first- the dark-psychopath anti-hero, followed by the loveable NRI who is torn between tradition and modernity, between the West and the East, and a small cluster of films that explicitly refers to the crisis of being a Muslim in India. Bhattacharya locates the affective pleasure of Shahrukh Khan’s stardom in the gestural economy of his on-screen figure. For his female fans, this gestural economy was made of wide open arms, the kiss on the neck, helping in the kitchen, talking, and listening to women kindly.

The oft-repeated refrain of the book, “Men are like Salman, but we want Shahrukh,” summarizes the texture of desires surrounding the two stars and their gendered fan base. The masculine, child-man figure of Salman Khan is juxtaposed against a more soft, kind and vulnerable masculinity represented by Shahrukh Khan. The refrain also summarises the stereotypical production of Shahrukh Khan’s feminized fan base. Who is the Shahrukh Khan fan we meet in the debates surrounding Pathaan? We will need an understanding of the fan base of Salman Khan to offer a tentative answer to this question. Bhattacharya’s work also focuses on the female fan, a mostly unavailable subject position within fan culture studies, which primarily centralises the subaltern male fan. Shohini Ghosh, who has traced and explored the fan negotiations around Salman Khan’s stardom, argues that Salman Khan’s largely subaltern Muslim fan base is partially a counter-discursive response to the rising Hindutva politics. Salman Khan, as we see here is established as a Muslim superstar and a form of Bollywood’s engagement with working-class Muslim audiences.

As seduced as I was by the Khula Hath, Khula Dil gestural economy in the genre of Shahrukh Khan romance (and I swear I waited for one at the end of Pathaan, which does not strictly belong to the genre), I became a Shahrukh Khan rasika after Raees, a powerful film about the fissures in the new Muslim identity in the years leading up to the Gujarat pogrom. In these new aspects of Shahrukh Khan’s star persona, rasikas like me read Muslim social identity’s pain, despair, and impasses. In Pathaan, these affective registers circling ShaHrukh are only thickened in very ambiguous ways. In the film, Shahrukh’s stardom is the setting and the lead character. What is easily discernible in Shahrukh Khan’s oeuvre in the last decade are strands of a Muslim social identity across films like My Name is Khan, Chak De India, Raees, and now Pathaan. The weathered melancholia of being Muslim in My Name is Khan and the belligerent yet honest figure in Raees shifts to a patriotic nationalist Muslim of the Yash Raj film Spy Universe, with crossover elements of cast and characters. [iv] It would not be a stretch to observe that across these texts are registers informed by his reel and real lives. The fervent patriotic nationalism of the film is constructed by dispelling all potentially ‘feral’ Muslim identities through pronouncements such as the justification of the 2019 Union of India’s accession of Kashmir and repealing of article 370 or the eternal enemy figure of Pakistan intelligence and its conspiratorial machinations. In the four years of Shahrukh Khan’s absence from the screen, Hindi cinema ecology has been changed by new institutional arrangements, vigilante publics, right-wing attacks against films and stars ( including Shahrukh Khan), proposals to recalibrate censorship rules, changing production and distribution infrastructure. Pathaan also entered a public sphere where the country’s streets, towns, provinces and textbooks are under serious threat to be wiped of their Muslim past. These interrupted histories frame Pathaan, Shahrukh Kha’s stardom and new fan formations.

Yet, Pathaan is not a text without its ambiguities, particularly in the metaphoric textual scape that it offers. The ambiguity is mined through multiple registers. Take, for example, Shahrukh Khan’s titular role, the nameless RAW agent Pathaan. He was born in a cinema hall and raised by the nation ( the joyous applause in the cinema halls thrilled the cinephile in me ). He felt an intimate connection with a village in Afghanistan that nursed him back to health when injured during an operation. The name Pathan, as the film points out, is derived from his Afghani family. In one broad stroke, Pathaan addresses and embraces the pan-South Asian fandom of Shahrukh Khan and the ‘epigenetic’ memories of the Indian subcontinent and the landscapes of partition. The film is also densely and ambiguously populated with iconography such as the Keffiyeh scarf, worn by Salman Khan, another RAW agent from the YRF Spy Universe. The film excels in creating scenarios that excel at such relational thinking. The assorted threads unspool like an elegantly coughed-up silk keffiyeh, where what seems like a blooming love story is often moving out of the fray and desires are productively askew.

There is even more to the register of ambiguity here. Besides establishing the YRF Spy Universe of cross-over elements, Salman Khan’s cameo entry conjoins the two fandoms and stardoms and the mutual perturbations of the two stars. The tensions and latent rivalry between the two stars are part of fan knowledge, which is effectively mobilised and deftly woven into an invisible paratext to Pathaan. This signage is not missed by the fans as the exhilarated fan response on the internet shows. The figure of Pathaan, with no particular provenance except for the cinema halls signals, the larger universe of the film seems to be one of affection- an affection for the moving image, resoundingly stated all through the film. Pathaan belongs simultaneously to the cinema hall and the nation, as the riveting dialogue states. The love for cinema turns considerably more takes intriguing turns towards the end. The title cards that roll at the end affirm this love for cinema, beyond all other love, by compounding the stardom of Shahrukh Khan and Salman Khan. These references to the cinematic universe work as an ultimate affective filter-. for all the lives, tragedies, celebrations and crisis that has rolled before on the silver screen. Animated by a sensibility to Hindi film history, crafts discrete incisions and specific sutures, as Paromita Vohra beautifully illustrates as a mnemonic device in her essay in this volume.

Ambiguities and contradictions like these populate the film and make it challenging to cast away Pathaan as a smooth, straight narrative of hyper-nationalism. These loose associations and intertextual play were not lost on fans, as one saw in fan reactions across social media. Pathaan, the rogue agent with a rebellious streak and non-conformist acts, was claimed widely as the most needed antidote to the viciousness of right-wing narratives, as an embodiment of a possible traditional idea of secularism and for some staking a rightful place for Muslims in the new Hindutva regime. The ambiguities of the film text also tap a vein with the audience that is more than the fascination for Shahrukh Khan, the star. Such an interpretive community of fans publicly claiming a film and a star as a secular and anti-Hindutva icon, is rare in Hindi film history. Asked differently, can the fan ascription of a traditional idea of secularism on Pathaan and Shahrukh Khan be limited to an analysis or does it render itself to reading political affect? The fan-star-film discourse that Pathaan generated in the public and social media sphere, both pre and post-release, resonates with some Salman Khan films in the last two decades. We saw an identical nationwide delirious fan response across different circuits of exhibition centres with the release of films like Bhajrangi Bhaijan.Pathaan allowed for a newer identity-laden fandom, in response to contemporary politics of hatred, ban culture and re-writing of history. It appears as if the fans who loved Raj-Rahul and the fans who loved Bhai came together in the theatres and on social media to shake hands, hug each other and cheer for Shahrukh Khan, the Muslim star.

Now to apprehend the untidy passions and eschew exceptionalisms, a sketch of the fan-star relationship is in order. The complex formations of star-fan relationships are to be understood beyond the frameworks of charisma and false consciousness. Recent theorizations of fan cultures locate them in conjunction with citizen-subject positions, as well as the unavailability and impasses of such subject positions (Srinivas 2009, Brugubandha 2018). Tracing the provenance and trajectories of fan culture and star power in South Indian film industries, Madhava Prasad has argued that the fans sought political existence for ethnic and linguistic nationalisms in the onslaught of the hegemonic drive for integration in nationalist politics. Pathaan and Shahrukh Khan can be as distant as they could be from 1950s South Indian fan cultures, and yet the axis of fan-star -politics exhibit a similar form of political engagement in virtual space. Just observing the intersecting moments of fan activity online takes us to the intense sensation of political engagement through cinema using intentional and unintentional methods. Analysing the film My Name is Khan and the burden that it took to speak of victimhood and oppression, Ashish Rajadhyaksha observes that the lack of freedom forces itself the popular to turn political, unbeknownst to itself ( Rajadhyaksha, 2022). Rajadhyaksha also points to Sharukh Khan’s search for exceeding the limits of representational devices in Hindi cinema. In re-scripting Sharukh Khan’s stardom after the crucial years of political crisis, what narrative techniques aided Pathaan? How does the mixture of elements of a spy universe animate the affective masculinity of the romantic hero? For a single flashing moment, did Sharukh Khan offer a consolidated figure of secular nationalist politics? Could one read this euphoria arising from the frustration of being beyond discourse while all other forms of political representation have come to a crisis? Does this intimate us of new political tools of communication that are shaped around cinema for different sections of the polity?[i] How do we read the politics itself in light of these new fan activities?

The ambiguity that pervades the untidy world of film passions exists parallel to other cinemas in the new OTT nation. I can’t help thinking of another more familiar film industry- Malayalam, where Muslim social and cultural life is densely and refreshingly narrated. A handful of films like KL 10, Sudani from Nigeria, Halal Love Story, Thallumala, and more recently Sulekha Manzil, unambiguously narrate Muslim social life without the burden and demands of nationalism. Thalumala (2022), a ‘montage bust’ in 9 chapters with two powerful lead actors in Tovino Thomas and Shine Tom Chacko, is a story of friendships formed through brawls, including a love story with its cinematic geography drawn across Kerala and the Middle East, its linguistic registers a mélange of lyrical Arabic and the specific Malappuram dialectic of Malayalam, Hadiths, muezzin calls, Mappila folk tunes and contemporary global fashion. I gesture to this other end of the spectrum of filmmaking to remind us of what Hindi cinema has to deny, erase and defer, to being recognised as a legitimate entity.

To return to the trope of ambiguity, the importance of the Muslim star as a symbol of religious tolerance makes Shahrukh Khan a site of ambiguities and contestations. As we had seen above, ambiguities mark the text, the star and the fans around the two What is the new constituency of fandom that we can discern here? From the pulsating crowds outside the cinema halls, we see more diverse enthusiastic male fans. Twitter presented a range of fans of all genders, broad South Asian audiences and diasporic Indians joining the celebrations, debates and controversies surrounding the film. Where are the female fans of Shahrukh Khan in this new ambiguous fandom? The composition and articulations of the new fandom emphasise that the feminized fan culture that Bhattacharya delineated is not the dominant fan in this scene. In an interview with Newslaundry, Shrayana Bhattacharya cited the example of a Muslim woman fan of Shahrukh Khan, who was momentarily disappointed and angry with him for not taking a public stance during the CAA- NRC debates- her love for Shahrukh powerful enough to wipe off the disappointment. Bhattacharya herself quips towards the end of the interview that Shahrukh Khan “should be the Prime minister”. Is there an arc of relations between these two statements? If we can discern SRK the romantic hero setting an aspirational modern conjugality and desirous masculinity in the past, in the recent shifts in his star configuration towards a Muslim star figure set ambitions for the woman-citizen subject? Has her ‘desperate seeking’ acquired new dimensions other than romantic fulfilment? In the reality of protest against CAA and NRC, we had emblematic Muslim women figures emerge. Cast against this backdrop, these individual statements are manifestations of political aspiration. The ambiguous new fandom, easily irked as Twitter feeds to show, seems to share the space with the loyal female fan who is perhaps desperately seeking fulfilment beyond the romantic joys. As she waits for another nameless figure Jawaan and a cameo in Tiger 3, and a rumoured Tiger vs Pathaan another film from the Yash Raj Films Spy Universe, dreams are deferred and fandom has acquired complex dimensions and enfolded with politics. The ambiguity and hesitation that marked this moment, can only be answered by the impending future of Shahrukh Khan’s star configuration and its manifest signs. Staying with the trouble of the film’s cautionary remark will perhaps help understand the ‘ambiguity’ of the fan. For now, the suspended temporality of waiting and the dense anticipation of the remark, “Mausam Bigadne Wala hein” might suffice.

Acknowledgements

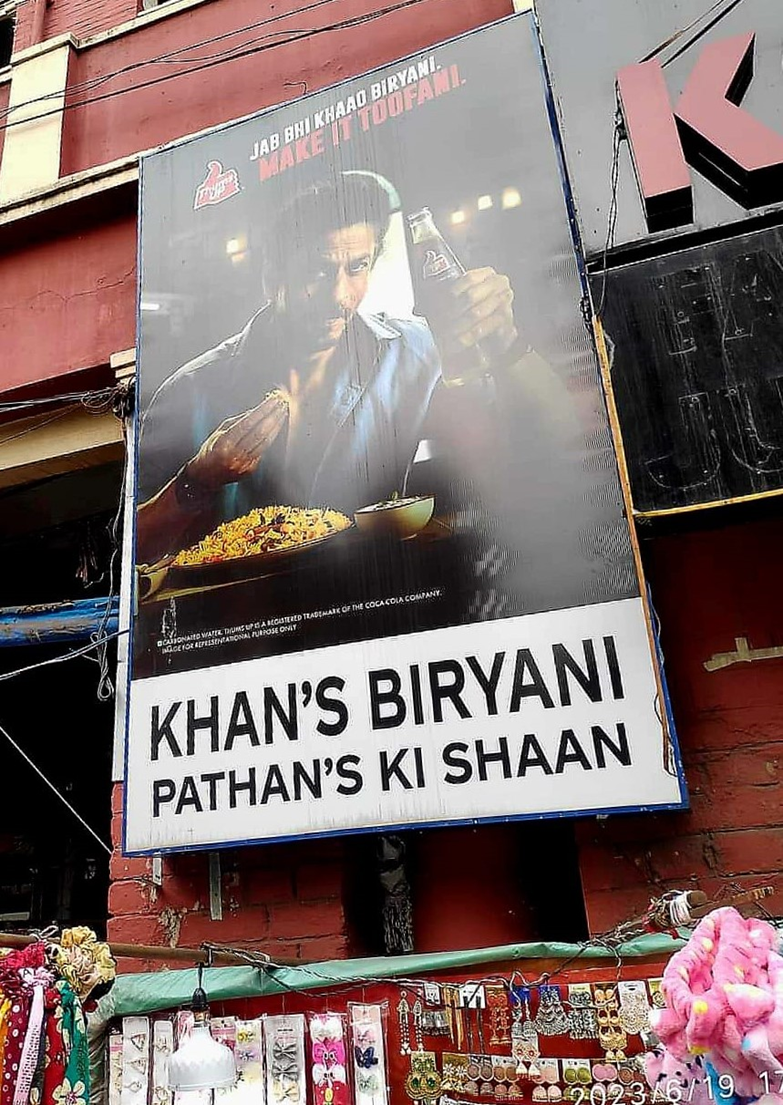

These reflections wouldn’t have been possible without the fun brainstorming initiated by Gita Chadda and the group of writers featured in this conversation. Many Thanks to Paromita Vohra for offering some particularly illuminating terms to think through and Khalid Anis Ansari for generously sharing the photo he clicked from Kolkata streets. I am grateful to my Hindi cinema companions, Anugyan Nag and Vebhuti Duggal for all the joi de vivre of conversations.

References:

Interview with Shrayana Bhattacharya, NewsLaundry, https://youtu.be/s-oUoxh2L_c, May 24 2022, accessed on 8th June 2023.

Bhattacharya, S. (2021). Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh: India’s Lonely Young Women and the Search for Intimacy and Independence. Harper Collins.

Bhrugubanda, U. M. (2018). Deities and Devotees: Cinema, Religion, and Politics in South India. Oxford University Press.

Ghosh, S. (2020). The Irresistible Badness of Salman Khan. Indian Film Stars: New Critical Perspectives, p. 193.

Ghosh, S ( 2015). “In Bhajrangi Bhaijan Hindutva meets its nemesis right at home”, The Wire, 24 July 2015, https://thewire.in/7159/in-bajrangi-bhaijaan-hindutva-meets-its-nemesis-right-at-home/

Mazumdar, R. (2000). From Subjectification to Schizophrenia: The ‘Angry Man’ and the ‘Psychotic’ Hero of Bombay Cinema. Making meaning in Indian cinema, 238-264.

Prasad, M. M. (2014). Cine-politics. Chennai: Orient Blackswan.

Rajadhyaksha, R ( 2021) “SRK, Citizen and Subject: What’s Next?” in Rashmi Sawney ed The Vanishing Point: Image after the Video, Columbia University Press, 2022. ( 224-249). Srinivas, S.V. (2009). Megastar: Chiranjeevi and Telugu Cinema after NT Rama Rao. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

[i] Liberal-Secular is a term used in a largely pejorative sense in recent public discourse, as a criticism against the mostly left ideological positions and secularism that this politics upheld. The idea of liberal secularism, as used and practiced by the left in general and its critique by the Indian right-wing in particular have to be understood against their ahistorical and biased views of religion and religious histories. In India, the secular liberal matrix that was formulated by Jawaharlal Nehru was increasingly brought under the scanner of criticism by the Hindu right wing as appeasement of minorities. The state-religion binary as practiced within the liberal secular model has struggled to defend itself against this political onslaught.

[ii] “ Time Pass or Subversion? Ira Bhaskar and Ghazala Jamil on Pathaan’s Politics, The Sandip Roy Show, Indian Express , February 19, 2023. https://www.freepressjournal.in/india/pathaan-controversy-now-pasmanda-movement-takes-objection-to-villains-name-demands-ban-on-shah-rukhs-movie

[iii] This drawing of cinema’s surplus has sometime occurred in other sites such as civil rights movements, women’s movements and sometimes advocacy campaigns. The processes involved here but differ from those in electoral politics.

[iv] Yash Raj Films Spy Universe is a fully fictionalized universe of characters and plots from a set of spy films that Yash Raj Films have produced with the titular spy figures of Tiger and subsequently Pathaan. A derivative of literary fictional universe and more specifically Science fiction, the Marvel cinematic Universe following the Marvel comics is the most known among such cinematic universes. Apart from conjoining narrative elements, it has been a powerful device of control over intellectual property , consistent fan base and star power. For details of the Yash Raj Film Spy Universe see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/YRF_Spy_Universe

[v] It is important to note that the Pasmanda Muslims expressed displeasure at the Villain Shabbir Ansari being named after their senior most leader and demanded a ban. https://www.freepressjournal.in/india/pathaan-controversy-now-pasmanda-movement-takes-objection-to-villains-name-demands-ban-on-shah-rukhs-movie

***

Bindu Menon Manil teaches Media Studies at Azim Premji University Bangalore.