Link to the editorial note and the panel discussion can be found here.

“While carnival lasts, there is no other life outside it. During carnival time life is subject only to its own laws, that is, laws of its own freedom.”

— Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World

“Hey, Mr Tambourine Man, play a song for me”

—Bob Dylan

SRK returns to the silver screen after a hiatus of four years with Pathaan (2023) as its eponymous protagonist. The film is now declared the highest-grossing Hindi film of all time. The star’s ardent admirers have many reasons to rejoice, and its commercial success is just one of them. As they rock to Jhoome jo Pathaan, they are aware that many people all across the world are doing the same—each validating the other. There is only one SRK and if he chooses to sing as Pathaan then his fans will dance to his tune. Just as they danced to “tujhe dekha toh,” “ladki badi anjaani hai,” “baazigar o baazigar” or “mahi ve”and amillion other SRK songs.

The Pathaan number however has a new color; a touch of besharam rang if you like! It is a victory anthem of sorts—for SRK and his fans. Here is a man who has been through hell and back, branded as a traitor to the country–his stardom rendered precarious and his family nearly torn apart. His teenage son was implicated in a drug possession case on flimsy grounds in October 2021 and spent a month in jail before being out on bail; surely it does not get lower than that! The past few years must have been lonely and traumatic for Khan. Celebrating an end to the long night, Jhoome re re-gathers a community around Shah Rukh a.k.a. Pathaan. The atmosphere is especially upbeat in light of the travails that dogged Pathaan since much before its release–with Hindu hardliner groups riled by its title, the saffron shade of its lead actress Deepika Padukone’s bikini, and Shah Rukh’s alleged “anti-India allegiances.” Splashed across social media are viral videos of fans grooving to its beats–in theatres, on campuses and on streets, not just in India, but also in Indonesia, Germany, France, Belgium, Australia and several other nations. Just to signal the tone and spirit of the euphoria—a Twitter post of an SRK fan club reads, “@iamsrk was featured on a French News show Le 1245 where they talked about #Pathaan, his global superstardom, and how the love of his FANs trumps hate” (Shah Rukh Khan Fan Universe, 2023). The success of the film is repeatedly described as the “triumph of love” by fans, critics, SRK’s friends and supporters from the film fraternity, and the star himself.

Such rhetoric reminds me of a very different setting—Amrita Pritam’s elegiac invocation of the Sufi mystic Waris Shah in “Ajj Aakhan Waris Shah Nu” [Today I Invoke Waris Shah], imploring him to speak from the grave and add a new page to Heer Ranjha, his epic saga of love–one that would heal a Punjab beset with the horrors of Partition. Tharu and Lalitha write, “Faced with the immense disorder that infects the world, the poet turns to Waris Shah…as the bardic gatherer of a people” (1995, p. 68). The parallel might appear far-fetched and maybe even audacious—Heer Ranjha being a timeless classic of star-crossed lovers, and Pathaan a testosterone-charged, hyper-nationalist commercial thriller. Yet, in disparate and historically situated ways, both dare to challenge the boundaries of patriarchy, nationhood and religious orthodoxy, rebuilding and reuniting a community of spectators across many borders. As filmmaker Anurag Kashyap declares buoyantly, “People are coming back to the cinema and people are coming back and dancing on screen. People are euphoric about the movie. There is euphoria and this euphoria is beautiful. This euphoria was missing. This euphoria is also socio-political euphoria; it is like making a statement” (“Shah Rukh Khan’s Pathaan,” 2023).

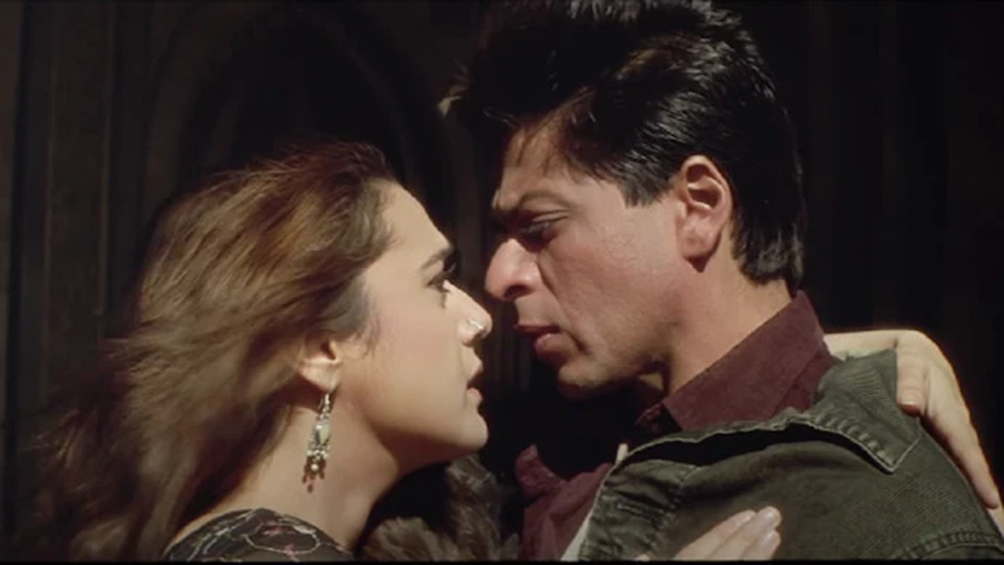

A Brief Look Back

Let me briefly sketch Khan’s chequered trajectory predating Pathaan. In the wave of rom-coms that was launched by Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (DDLJ, 1995), the Shah Rukh of the 1990s blended vulnerability, charm, charisma, and not a small dose of campiness. Who can forget the unruly mop of hair, dimpled smile, the dewy skin look with no hint of facial or body hair, and not to forget, the hamming? Even the villainous K-K-K Kiran of Darr (1993) would become something of a cool urban slang (playfully mimicked by Khan himself in Pathaan). As Gopinath argues: “SRK’s urbane, well-spoken, cosmopolitan masculinity wedded to a full-throttled belief in meritocratic capitalism, both as star and in his cinematic roles, made him the poster-boy of India’s much-celebrated entry to the global capitalist economy. His sensitive, emotional, and ambitious cosmopolitan persona spoke to the Indian neoliberal ideal of a romantic family man (always rendered as upper-caste, upper-class Hindu man) who has the potential to conquer the world” (2018, pp.1-2).

Through the 1990s and well into the 2000s, SRK’s cosmopolitan/Indian/secular/Hindu persona glosses over his Muslim identity with casual ease. Narratives about his personal life largely centre around the struggle and drive behind his success (fitting right into the neoliberal, meritocratic narrative), his marriage to his childhood sweetheart—a Punjabi Hindu woman, and his participation in Eid/Diwali/Holi with equal zeal. When his Muslim identity is referenced, he is emblematic of the “good Muslim” in the Nehruvian sense—secular, nationalist—with no overt/disruptive markers of Muslimness. Notwithstanding his soft masculinity, in fact, because of it, SRK attains stardom and cultural authority wielded in Indian cinema so far by Amitabh Bachchan alone. Their screen personae are widely divergent; “Bachchan’s stardom was predicated on a masculinity of controlled anger and explosive violence, while SRK’s masculinity was shaped by androgynous vulnerability and uncontrolled energy and spontaneity” (Gopinath, 2018, p. 9). SRK would retain this space of authority—never stereotypically masculine yet composed, unyielding, never abject—even in the worst of times. This is no small feat, given how incessantly and viciously his Muslim identity has been invoked over the past few years.

Being Indian/Being Muslim

As the Raj-Rahul era wanes in the 2000s and SRK slowly transitions to more mature roles, we note a quiet owning of his Muslim identity—resurfacing every once in a while in the form of anecdotes, nostalgia and cinematic performances. In more than one interview in 2014, he fondly speaks of his waalid hailing from Peshawar. He recalls visiting the city as a teenager and hopes one day he too could take his children there. In other video clips from the same phase, he speaks of the bond between the people of India and Pakistan and of his Pathaan roots.

During this period, he continues to play the upper caste Hindu protagonist with panache, but one notes a shift. In the much acclaimed Swades (2004), he is Mohan Bhargava, the global technocrat with an enviable career at NASA. But he gives it all up to return to a village in India that lacks the most basic resources, so he can contribute to its growth. The character embodies a Nehruvian moral authority—a coming together of middle-class cultural capital and socialist idealism. SRK’s earlier NRI/upper caste roles had skirted the socialist burden. As Consolaro observes: “The model inaugurated by Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jaayenge (1995) introduces the hybridized Indian who can adhere to core Indian values while embracing what the West has to offer….What makes him a ‘real Hindustani’ is a cultural identity rooted in patriarchal and bounded concepts of family, protocol, honour, nation, entertainment, gender roles, and spiritual practices” (2014, p.11). With Swades, Shah Rukh ventures out of the “safe zone” into a less ebullient space, engaging questions of caste, poverty and social justice.

Serendipitously enough, 2004 is also the year of Veer Zaara—a story of the undying love between ill-fated lovers, Veer Pratap Singh (Khan), an Indian Airforce Officer and Zaara Hayaat Khan (Preity Zinta), the daughter of a Pakistani Politician. Suffused with the tenderness, sacrifice, and ethereality of the protagonists, the narrative generates a strong sense of identification with the lovers in the audience and a longing for a world without boundaries. As a film critic points out, in a country riddled with sentiments against Interfaith love, Veer Zaara takes the bold step of portraying a love story between an Indian man and a Pakistani woman (Rakshit, 2020). Veer Zaara re-invokes the legacy of Waris Shah’s Heer Ranjha. Almost two decades later, Pathaan would re-stage the romance between a man and woman divided by national borders, but in a more stylized, Bond-like fashion, without the spirit or intensity of Veer Zaara. However, as we well know, star/film texts do not remain contained in a specific plot; they crisscross and overlap and resonate with one another.

In Chak De India (2007), SRK portrays Kabir Khan, the disgraced former captain of the Indian men’s national hockey team, labelled a traitor after losing to team Pakistan and the subsequent surfacing of a photo of him in media, shaking hands with the winning captain. When a friend attempts to comfort Kabir with “ek bhool toh sabko maaf hota hai,” [Everyone is forgiven for one mistake], Kabir responds with a poignant “sabko?” [Everyone?]. Chak de allegoricallymirrors the “burden” of every Indian Muslim. As Devji reflects, “The ghost of Pakistan is not simply the spirit of Muslim guilt; it is also a spectre which, by transforming all subsequent struggle into the struggle for “another Pakistan,” ends up making Indian history into a series of variations upon the theme of partition as an original sin” (1992, p. 2). My Name is Khan (2010) takes up a similar theme, addressing the representational dilemmas of the Muslim–the scene now set in the U.S.A. in the aftermath of 9/11. SRK portrays Rizwan Khan, an autistic man who undertakes a picaresque quest in search of human connections in a world torn by religious and ethnic prejudice, obsessively disavowing the now globally sanctioned link between his Muslim name and “terror.”

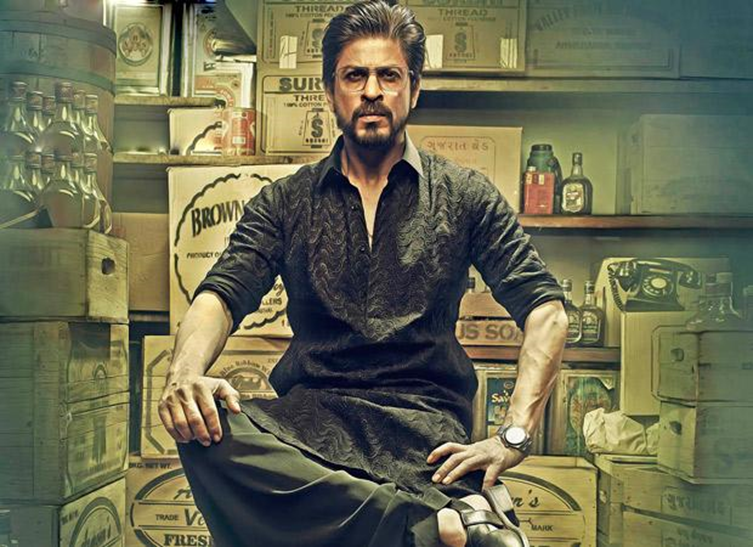

In Raees (2017), SRK plays Raees Alam, a bootlegger from Gujarat, running an illegal liquor trade in a dry state, also the bastion of Hindutva. Raees is not the “good Muslim,” by any stretch of the imagination—a figure despised by the proponents of Hindutva but also one that does not find any easy fit within the secular liberal imagination. Poonawalla notes, “The real test is to disabuse the stereotypes associated with an identity by portraying it as a well-rounded human character, with all its flaws and shortcomings and to then say, ‘Accept this’”. Comparing SRK’s Raees to Aamir Khan’s Tare Zameen Par (2007)and Dangal (2016), he suggests that the latter has always opted for political correctness, catering to a multiplex liberal audience that relates to the “social relevance” of his films. Shah Rukh, on the other hand, has the “daring”–a term resonating with the dialogue “baniye ka dimaag aur miyanbhai ki daring” from Raees–to reopen a wound buried deep in the secular psyche of the nation ( 2017).

SRK’s oeuvre anticipates Pathaan (2023), yet it is distinct from anything he has done before. It is founded on a recognition that he can no longer be what he was, tugging at the heartstrings on the sheer strength of innocence, charm, charisma or his unmatched star pull. He must now search for a different grammar, in tune with the new exceptional times—a “state of exception.” The grammar of the spyverse—with its exaggerated machismo, spectacular cross-country action sequences, and sinister threats of terror from across the border—allow Khan to re-cast himself as a patriot par excellence. The rugged, weathered, thrill-seeking masculinity of SRK as Pathaan is a stark contrast to the androgynous charm of Raj-Rahul or the brooding nationalism of Mohan Bhargava (with no chest-thumping). Yet, as we will see, what is lost/repressed, returns in Pathaan, couched in fleeting references, jokes, subtexts and slippages.

Masquerade

Pathaan has received criticism from several quarters for its hyper-nationalist, militarist jingoism–unquestioning compliance with the Indian government’s decision to revoke Article 370 that granted partial autonomy to the state of Kashmir, the predictable marking of a disgruntled Indian ex-soldier and a Pakistani general as “Enemy,” and through such routine emplotment, preempting any scope for a political engagement with knotty geopolitical histories and the perspectives of the Kashmiris themselves.

However, as Menon points out, “Like all cinema, Bollywood too trades in fantasy…But Bollywood cinema can also be deeply political, and the hallmark of this politics is play: Play as a mingling of genres, play as pushing against borders, play as critique, play as laughter, play as syncretism” (2023). Thus, in Pathaan, the ever and over-present narrative of military nationalism is now and then subverted, transgressed, and disrupted. The film opens with a description of the abrogation of Article 370 as a “unilateral decision” by the Indian parliament. Menon draws attention to the choice of the phrase, one that has hardly found a reference in popular media and yet is slipped into the narrative of the film (2023).

The transgressions are many, speaking to an audience familiar with the grammar and protocol of Bollywood—through coded messages, multivocal signs and spectacles. Jingoism is like the discourse of the intoxicated; slips of the tongue are always possible. Tell-tale references to SRK’s past personae as well as an older Bombay cinema are scattered throughout the film. When Rubai (Deepika Padukone) asks Pathaan if he is a Muslim, he recalls growing up in an orphanage after being found abandoned at a cinema theatre. I am struck by the choice of a cinema hall as the site to forsake a child! Why not a mosque? Or a temple? Indeed, if Pathaan was found and rescued at a temple, it would have further shored up his affiliations and loyalties to the hegemonic community of the nation. I read here an allusion to the Bombay cinema that became a homing space for many Muslim stars, scriptwriters, and lyricists in post-independence India. [i]

Pathaan has no blood ties but is deeply bonded with the people of a village in Afghanistan, adopted by them as part of their Pathaan clan for having saved the lives of their children. Each year he celebrates Eid with them. The Pathaan figure has a recurring association with Hindi cinema, emblematic of the largehearted, gruff and loveable Muslim yet reminiscent of transnational and trans-geographic connections. We may recall Balraj Sahni’s Kabuliwala (Kabuliwala, 1962) or Pran’s Sher Khan (Zanjeer, 1973). I remember being moved by a great love for my country as a child each time I listened to the mellifluous “ae mere pyaare watan” [Oh my beloved country…] from Kabuliwala on the radio, without knowing that it expressed the protagonist’s longing for his homeland in Afghanistan and the little daughter he left behind when he set out for India on business. The subsequent realization of this fact only reinforced my pathos and empathy, cementing my identification with the Kabuliwala (sublimely essayed by Sahni)!

As Chakravarty argues, “the male star’s body in Bombay film has lent itself most consistently to various forms of masquerade” (1993, p. 203).

The male hero as the centre and source of narrative meaning is “resemanticized” into a mode of instability and dispersion of meaning. Forms of disguise, impersonation, and masquerade are the visual means that serve to render this move from the natural to the acculturated body, allowing the spectator means of recognition of his/her social world within the world of the film through the hero’s “play” with the signifiers of dress, accent and gesture. (Chakravarty, 1993, p. 200)

A multitude of communities (cinematic and extra-cinematic, national and sub/extra-national) crisscross the Pathaanscape, evoking, disrupting and re-making the idea of the nation. Let me bring in some scenes that might be illustrative. Just before Salman Khan makes his cameo appearance, a black and white checkered keffiyeh–symbolic of Palestinian resistance–dangles from the ceiling of a train, unleashing frenzied hoots from the audience. Salman appears in his Tiger avatar, donning the iconic scarf look from Ek tha Tiger–yet another spy franchise from Yash Raj Films. As an excited media report proclaims: “Trust me, it has to be the loudest cheer, ever in cinema history, where people were cheering so loud for a frickin piece of cloth!” (Jain, 2023).

The bonding between the two Khans is rife with allusions to their super successful Karan Arjun (1995) pairing, off-screen friendship and shared standing/precarity as India’s most popular Muslim actors. Recall the heart-to-heart between the two once all adversaries are decimated and “order” is restored. We see Shah Rukh tending his aching leg. They confess to each other that their bodies are giving out after thirty long years of “action,” in need of painkillers now and then. This is a bold admission in an industry where a male superstar’s masculinity is directly linked to the mythology that he does not age, and is entitled to romance women less than half his age (as both Khans have repeatedly done in their films). They then wonder if it is time to pass on the mantle. After some exaggerated deliberation, they are unable to zero down on a “fit” successor and shake hands on Shah Rukh’s cheeky declaration, “Humein hi karna padega bhai, desh ka sawal hai, bachhon par nahin chhod sakte” [We have to carry on brother. After all, it is a matter of the country, can’t leave it to the children!]. One can barely miss the reference to the new kids on the block in Bollywood as also older actors like Akshay Kumar, Ajay Devgn and Sunny Deol who have been churning out films high on shrill patriotism. The word-play between the Khans is an act of re-claiming Bollywood and the nation, and a reassertion of faith in the inherent potential of cinema to draw people together, in the face of hate and calls for bans and boycotts. A lot of hard work and determination underwrites this reclaiming; after a draught of four years, Shah Rukh returns with an enviable, age-defying physique, performing spectacular action sequences in Pathaan. Anurag Kashyap recognizes this labour: “Shah Rukh Khan itna haseen itna sundar pehle kabhi laga nahin…. Aur itna khatarnak action hai, Shah Rukh ke liye pehli baar aisa role hai” [I have never seen Shah Rukh Khan so beautiful …The action sequences are so dangerous, it is the first time Shah Rukh has done such a role] (Kaur, 2023).

It is hard to miss the Urdu and Arabic ethos of the film, resonating with the now-forgotten Islamicate tradition of Hindi cinema. Note the exchange of Islamic greeting between the lead actors, inserted into the suave, cosmopolitan setting of the spyverse—Shah Rukh’s elegant “Wa alaykumu salam wa rahmatullahi wa barakatuh” as a response to Deepika’s “Assalamu Alaikum.” In an interview following the release of Pathaan, SRK invokes Manmohan Desai’s cult classic Amar Akbar Anthony (1977), an ode to the syncretism of Bombay cinema: “This is Deepika, she is Amar, I’m Shah Rukh Khan, I’m Akbar and John is Anthony… We are ‘Amar, Akbar, Anthony’. And this is what makes cinema… There are no differences any one of us has with any culture. We are hungry for the audience’s love. All these crores are not important…The love we receive…nothing is bigger than that.” Not surprisingly, Deepika can easily travel across genders–becoming Amar (played by the brawny Vinod Khanna in the original), given that Shah Rukh is one of the few male stars in Bollywood known for traversing male and female-designated spaces and never anxious about his heroines commanding equal screen space.

Love-Loss-SRK

I am constantly struck by the way Shah Rukh speaks of love and is associated with love, repeatedly, unabashedly—by fans, co-stars, and critics. I remember my mother winding up housework to watch him in Circus on Doordarshan (one of the TV series he started his career with), and musing, “There is something so warm about this boy!” As an older, staid academic, aeons after my teenage years, SRK is the only actor for whom I have feelings that closely resemble “love.” A fifteen-year-old writes, “In the end, this is the magic of Shah Rukh Khan. If you love him, you love him the way he loves his heroines – unabashedly, inexplicably, and forever” (Bhattacharjya Gupta, 2022). His co-star Rani Mukerji says, “Nobody can love like Shah Rukh.” John Abraham, SRK’s chief antagonist in Pathaan, declares his love for the actor with barely concealed queer overtones: “I don’t think he’s an actor anymore, he’s an emotion. Maybe that’s why I nearly went to kiss him in a lot of scenes” (mid-day, 2023). Add to this the connections that SRK makes between being alive, being positive, and giving and receiving love. At the Kolkata International Film Festival, SRK spoke a dialogue from Pathaan before its release, sending the audience into raptures: “Apni kursi ki peti baandh lijiye, mausam bigadne wala hai. He concluded with ‘Duniya kuchh bhi kar le, main aur aap log aur jitne bhi positive log hain sab ke sab zinda hain” [Fasten your seatbelt, the weather is about to turn turbulent…Let the world do whatever it likes, but me and you, all of us who think positive, are alive!].

In a context where his Muslim identity would Otherize him, to (re)cite “love” is a radical and utopic act. As bell hooks writes, “No matter what has happened in our past, when we open our hearts to love we can live as if born again, not forgetting the past but seeing it in a new way. We go forward with the fresh insight that the past can no longer hurt us” (hooks, p. 129). In a different context, Kristie Dotson states how it requires a radical love for black people to practice black philosophy in academia, precisely because it calls for a daring that defies the current dominant reason (2013, p.38). For SRK to be Indian and Muslim, to perform both adaab and his signature open arms gesture, to let his cinema carry traces of an ethos and identity that have no space in Bollywood today–is emblematic of a similar radical love. Paromita Vohra sums it up, “Lovers often enter a party in disguise. Pathaan comes disguised as an action film. But everyone knows, it is, in fact, a love story—between Shah Rukh Khan and his public” (Vohra, 2023).

Known for his witty and candid public interactions, Khan recently declared that he would no longer speak about his personal life nor give interviews. Instead, he would let his work speak, as he did with Pathaan. We may not again hear SRK speak about the fakir who blessed him in Ajmer Sharif during his struggling days; no more nostalgia about his ancestral home in Peshawar. He may not again look at a woman from Pakistan with his entire soul in his eyes (Veer Zaara, Raees). He is most likely not going to articulate concern over the growing religious intolerance in the country as he had some years back. But “love” will surely continue to be constitutive of his (cinematic) world and his ties with his fans and the nation, as it does in Pathaan. It will return in new ways, with the spectres of the old looming in the background. As Pathaan demonstrates, a lot remains in the domain of possibility, in indirections and allusions; spilling out of strictly military or nationalist protocols. We need to look out for subterfuges, subtexts, pantomimes, masquerades and shadow plays, where desires, not always officially sanctioned nor fettered by the constraints of identity, play out in half-light.

Acknowledgements: These thoughts took shape because Gita Chadha gathered a small community to share ideas on/around Pathaan. I remain grateful to all the authors in this group for the thought-provoking yet warm and informal conversations.

References:

Bhattacharjya Gupta, Tara. (2022, June 28). Fan: Why I love Shah Rukh Khan. Agentsofishq. https://agentsofishq.com/post/fan-why-i-love-shah-rukh-khan

Chakravarty, S. S. (1993). National identity in Indian popular cinema, 1947-1987. University of Texas Press.

Consolaro, A. (2014). Who is Afraid of Shah Rukh Khan? Neoliberal India’s fears seen through a cinematic prism. Governare la paura. Journal of interdisciplinary studies.Notes

Devji, F. F. (1992). Hindu/Muslim/Indian. Public Culture, 5(1), 1-18.

Dotson, K. (2013). Radical love: Black philosophy as deliberate acts of inheritance. The Black Scholar, 43(4), 38-45.

Gopinath, P. (2018). ‘A feeling you cannot resist’: Shah Rukh Khan, affect, and the re-scripting of male stardom in Hindi cinema. Celebrity Studies, 9(3), 307-325.

HT Entertainment Desk (2023, February 01). Shah Rukh Khan’s Pathaan started a revolution in India, says Anurag Kashyap. Hindustan Times.

Indian Express, (2023, January 30). John Abraham says Shah Rukh Khan is an “Emotion and National Treasure. The Indian Express. https://indianexpress.com/article/entertainment/bollywood/john-abraham-says-shah-rukh-khan-is-an-emotion-and-national-treasure-8413624/

Jain, Aaliyah. (2023, February 02). TBH, Salman Khan’s ‘Scarf’ deserves an Oscar for the best cameo appearance in ‘Pathaan’. Scoopwhoop. https://www.scoopwhoop.com/entertainment/salman-khans-scarf-best-cameo-appearance-in-pathaan/

Kaur, G. (2023, January 30). Anurag Kashyap calls Shah Rukh Khan ‘The man with the strongest spine’: He spoke loudly on screen. Outlook.

Menon, M. (2023, February 14). How ‘Pathaan’ gives the secular credentials of Bollywood a new boost of life. Frontline.

Mid-day Online Correspondent. (2023, February 01). ‘Pathaan’: Shah Rukh Khan, John Abraham react to their almost-kiss memes. mid-day. https://www.mid-day.com/entertainment/bollywood-news/article/pathaan-shah-rukh-khan-john-abraham-react-to-their-almost-kiss-memes-23268355

Poonawalla, S. (2017, January 31). Shah Rukh Khan as Raees does more for nationalism than Aamir in Dangal: https://www.dailyo.in/arts/shah-rukh-khan-raees-hindutva-indian-mulsims-bollywood-nathuram-godse-kailash-vijayvargiya-15409

Rakshit, R. (2020, November 17). The relevance of Veer Zaara 16 years after its release. 5X Fest. https://www.5xfest.com/5xpress/the-relevance-of-veer-zaara-16-years-after-its-release

Shah Rukh Khan Fan Universe [@SRKUniverse]. (2023, January 28). Man of the day–Shah Rukh Khan. #ShahRukhKhan #SRK [Tweet]. https://tinyurl.com/38nvu9na

Singh, J. (2019, September 26). The city Manto loved and lost. Mumbai Mirror. https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/news-media/mumbaimirrored-the-city-manto-loved-and-lost/articleshow/71301785.cms

Tharu, S. J., & Lalita, K. (Eds.). (1995). Women writing in India: The twentieth century (Vol. 2). Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Vohra, Paromita. (2023, July 13). Mausam ki Jankari. Mid-Day.

https://www.mid-day.com/news/opinion/article/mausam-ki-jankari-23267759

[1] Saadat Hasan Manto’s aching, desperate love for Bombay comes to mind: “I stayed in Bombay for 12 years. And what I am, I am because of those years. Today, I find myself living in Pakistan…wherever I go, I will be what Bombay made me. Wherever I live, I will carry Bombay with me” (Manto, as cited in Singh, 2019).

***

Deepa Sreenivas teaches at the Centre for Women’s Studies, University of Hyderabad. Her research interests and publications include popular visual culture, childhood studies and feminist pedagogy. Her fave past time is watching films and lazing, and her pet peeve is she doesn’t get to do this enough.