Link to the editorial note and the panel discussion can be found here.

This piece will try to locate anxieties around the Hindu right and the persona of Shahrukh Khan by analysing the present Pathaan moment. First, as women’s studies scholars, we attempt to understand the politics of gender, community, and sexuality in the context of Pathaan andthe rise of Hindu nationalism. We trace Shahrukh Khan’s characters from Fauji to Pathaan, via My Name is Khan and Chak De India. Interspersing our relationship – as cis heterosexual women-with the icon, we move between the persona and the actor. In a sense, this maps the question: what does Pathaan mean for us as feminists in the present moment? How do we read the film, considering the complexities of a ‘Muslim’ persona playing a spy who is needed to safeguard the nation? Reconfiguring the question asked by Anuradha Roy (2020) about third-world women[i], we seek to ask whether nationalism offers any liberatory politics for a Muslim superstar in contemporary India. The exercise of writing about SRK jointly is fascinating because we belong to different generations thus the way we read SRK is not distinct but displays how the idea of romance and love are context specific. While both of us find Bollywood and SRK fascinating, we differ in our ‘fan-dom’. We begin by reflecting on why we are fascinated with SRK and ‘Pathaan’ especially since we found neither the story nor the film to be very innovative. We explore these disjunctions and coherences, as ways of reflecting on contemporary India.

Locating ourselves as SRK fans

Sneha is a reluctant[ii] Shahrukh Khan fan.

My love for him was certainly not love at first sight. It was a slow burn, creeping up on me over time. A big part of this was my discomfort with the idea of fandom and the gendered dynamics of the female fan of a male actor. As an adolescent, I thought of fan girls as “giddy, overtly feminine, swooning over the star” sort of people and my sense of self as a serious, studious and sincere girl did not match this image. I did not want to be ‘her’, putting posters on walls, sticking photos in an old notebook or gushing about him. I wanted to be taken as a mature, thinking person. Adulation for a hero I had never met and wasn’t likely to, did not contribute towards that persona. The initial outings of Shahrukh that I had seen were Bazigar, Darr and Anjaam and while there was something romantic about the obsessive lover, I found his violence jarring. I wasn’t entirely sure of how to reconcile my attraction with my fear. However, I distinctly remember a winter evening in 1995, sitting on the balcony of my house with my best friend who had just seen DDLJ (Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge). I had not watched the film yet and she proceeded to give me a scene-by-scene recounting of the film. What has stayed with me is the excitement we felt about Raj keeping a fast with Simran and his easy banter and sharing work with the women of the household. We didn’t have the language to express it then, but it signalled a different kind of masculinity from the ones we were used to seeing in Hindi films. Though I cringe today to think of the symbolism of an ‘equal’ Karwachauth, it was for its times an extraordinarily sensitive gesture from a man. I think it was with Raj that my love affair with Shahrukh began. Over some time, it has been much more the person rather than the persona that I have come to fall in love with. It was never the films he was in, but rather the things I heard him say outside of them that made him interesting to me. It was also a growing consciousness of what he stood for, against the backdrop of a changing India making me fonder of him. I remember 1992 and seeing the images on television of the demolition of the Babri Masjid as a ten-year-old. Coming from a Bramhin, middle-class Maharashtrian family, where pirated videos of the need for Kar-seva were being watched, I remember the fear of the Mumbai bomb blasts more than the anti-Muslim violence. However, by 2002, I was a different person, and much more conscious of the politics of the right as well as of my caste privilege. In that context, I first started thinking about the enormity of Shahrukh’s stardom in a country like India. This also coincided with the changing trajectory of my relationship with the ‘popular’- from my initial discomfort to own up to my passion for it to a feminist reading of the popular as a site for reinforcement of patriarchy to a more nuanced feminist lens of understanding the popular as a complex site of contestation over meaning. The popular especially Hindi films as objects of inquiry came to be theorized in complex ways and my exposure to that scholarship which moved from victimhood to complex theorization of agency, of the messiness of the ordinary, of the contradictory ways in which audiences made sense of cinematic products, shaped my viewings and understandings. As my feminism matured, so did my understanding of reading cinema. From asking if representations of masculinities and femininities were authentic, I realized that asking what these representations allowed for, what they made visible and what they hid were more productive questions. Bringing a feminist lens was more than asking what men and women were ‘portrayed’ as, it was asking questions about nation, sexuality, class, caste and how gender worked through and against these. I unlearned the premium on realism as desirable and learnt instead to pay attention to what we thought was desirable!

Three films in the period after that have stood out for me, making me a Shahrukh fan – Chak de India, My Name is Khan and Raees. To me, Shahrukh embodies the liminality of the Indian Muslim. When he moved from the Raj/Rahul/Aryan to being Kabir/Rizwan/Raees/Jehangir, he brought to the fore the fractures that make up the nation and also possibly suggested ways of bridging the chasms. As someone whose work is interested in women’s movements, to me looking at popular cinema was also about the questions of mass connections, how women and men were not stable categories, and how we would have to think about the refractions of community and caste. Even as I think of the desire of the majority of Hindu women for a Muslim superstar like Shahrukh, I also wonder what would it mean for a Muslim woman to be a female superstar in today’s India. What shape would the desire of Hindu men for her and her persona mean, in these vitiated communal times? Who would be the audience of a film like that? And what still allows for the contested but continued stardom of the Khans in a fast-changing India?

For Swati who is a die-hard fan of Shahrukh Khan, this exercise to recall her love for him refreshes the critical mind and kindles the romantic heart.

SRK was one of my first crushes. In 1989 I was just 16. I saw SRK as Abhimanyu Rai in Fauji. He made me dream of a man who is tough yet sensitive, clichéd yet real. From Fauji to other romantic films of SRK I was witness to a love which was unconditional, playful, silly, sweet, and obsessed. He offered an image which is not intellectualised or idealised and, I think, not over-masculinised. On reflection, I think his overall persona attracts women across age groups aspiring for unconditional love. SRK in Fauji is a soldier. Fauji, probably one from the early lot of serials depicting the life of soldiers, offers SRK as adorable/caring yet masculine enough to protect the boundaries of the nation-state. His entry into Bollywood where he dominated the romantic genre except for films like ‘Darr’ / ‘Bazigar’ also offered the aspiration of unconditional love to the female protagonist and viewer. For us, in college, he appeared as the perfect man ready to protect his ‘woman’ expressing love/care yet not crossing the ‘boundaries’. This was also a decade where there was chaos in the nation, we were facing an economic crisis and upsurge of different backward caste groups which caused interruptions in the life of the middle class of this country (later I understood why they need to be called democratic upsurge). Accepting liberalisation was presented as the only option to save the nation. This not only affected the economy but also had an impact on the social and cultural life of Indians. Looking back, SRK’s DDLJ which shaped our idea of romance also took us through foreign locations and allowed us to dream and aspire for that kind of romance and dream to go to that land which is foreign. The fact that those living there preserve Indianness made it even more attractive. Where transnationalism became a possibility and going back to the roots became the new modern for us. Post 2000 we saw many such films depicting the anxiety of men and women to preserve ‘Indian’ culture where again SRK appeared as the desirable Indian man protecting the honour of a real ‘Indian’ woman. As this was the period where we were trying to reverse the idea of ‘brain drain’ and were liberating NRIs (Non-Resident Indians) from the representation of a bigda huwa / fallen Indian NRI to sanskari / cultured Indian living outside of India. Overall Bollywood films and SRK’s films were fitting into this broader narrative of the nation. This decade also was significant as we witnessed the shift in secular democratic values and overwhelming acceptance of Hindu identity in India. Few films released in these decades were questioning these changes and trying to make sense of terrorism, separatist movements and the overall rise of fanatic Hindutva, SRK films were significant to this genre as well. I clearly remember the SRK starrer ‘Dil Se’ addressing the crisis in Assam. Also, ‘Chak De’ addressed the victimisation of Muslims and the defamation of women who want to make sports their careers. However, post-2010 the space to critique the majority community or the state, started shrinking and we entered the next phase of consolidation of the majority community in India and enhanced anxiety around the minority community, mainly Muslims. While this was a local phenomenon, it also had a global register. SRK’s ‘My Name is Khan’ released in 2010, the controversy around it and the way he dealt with it again made me question his image of merely a romantic hero[iii]. The story was woven around the love for the family yet went beyond it. The entire discussion pushed me to think, can we understand love/care in isolation from the family, community and nation that shapes it? Thus, like my relationship with my family is at once fraught / with love / distant yet connected, so is my relationship with SRK’s persona. It feels like being connected with something(one) utterly arrogant, distant, and still adorable.

This brings me also back to what I read, understand and believe as a feminist who is trying to make sense of the gendered nature of the construction of the identity of the nation, community and family to underline that foregrounding gender while analysing nation/community or family is not optional. Thus, reflecting on SRK’s films and his persona allows me to engage with the works which look at nation, community and family through a feminist lens. Over the period with my introduction to feminist scholarship, I became uncomfortable with many romantic films or films like ‘Darr’ or ‘Bazigar’ which promote much-critiqued ideas of control over women and ‘use’ of her to teach lessons to the family/community. This has a strange reverberation of connection drawn by feminists between control/ ownership over women’s sexuality and how ideas about honour/shame/pride are woven around women of that family/community and nation. The close engagement with the feminist scholarship not only sharpened my critical capabilities but also enhanced my ideas related to what ‘love’ / ‘passion’ means; can we aspire for more democratic yet passionate and unconditional love and companionship foregrounded on the principle of democracy?

It is then from this divergent fandom and shared disciplinary location that we attempt to make sense of the film and its meanings for the contemporary.

Locating SRK and the contemporary

The Hindi film industry is one of the largest in the world and much has been written about it. Surprisingly it has been a focus of scholarly work and debates only in the last 4-5 decades. From the oft-repeated founding myth of Phalke wanting to “see our Gods on screen”, the relationship between the Indian nation and cinema has been an important one. Cinema in India, particularly Hindi cinema self-identified as a space for the articulation and popularization of the idea of the nation, even as the State saw it as frivolous and mass entertainment, not to be given a sympathetic policy environment. Further, as we enter into new phases of capitalism, cinema has been conceptualized as an important site to understand the changing relationships between the state, market, society, and even the changing space of the urban economy. Over time, the relationship with the state has also changed, with popular cinema being celebrated as a tool of India’s ‘soft power’ by the state, as opposed to its earlier disdain for the popular. Studies of the relationship between cinema and nation have tended to concentrate on blockbuster hit films and what they tell us about the social history of the nation (Virdi 2003), on the relationship between nation, technology and production (Vitali 2008), focussing on the ideology of the film (Madhava Prasad 1998) as well as focusing on the oeuvre of particular directors/ film-makers (Dwyer 2002). The site of popular cinema has been argued to have echoed the messier dimensions of democracy’s bid for inclusiveness, exhibiting and channelling mass energies that exceeded the normative and procedural prescriptions of elite modernity. In this context, it becomes important to explore the possibilities that cinema opens up. The disjunction between official plans for the cinema’s role in the national culture, and the prevailing culture of cinema, afforded the working out of a variety of critical conflicts with the ambition of nation-state architects to institute a civil social form with adequate cultural constituents. It is in this context then, that an examination of Pathaan is vital, for what it seeks to counter and exceed. As feminists seeking to make sense of it, it is also important for us to ask what masculinities and femininities it represents and how they link up to the nation. In this regard, the ambiguous nature of the identity of both Tiger and Pathaan in the film, their interactions around the fragile nature of their masculinities, the heroism of a Muslim, Pakistani woman in saving the Indian nation and the distinct perspectives of Jim and Pathaan about the ‘nation’ embodied as woman are worth noting, in the context of feminist scholarship around the gendered discourse and practices of the Nation (Yuval-Davis, 1989; Enloe, 1990).

‘Pathaan’ is a YRF production and its important to locate it in the trajectory of Yash Chopra and Yash Raj films, as well as the filmography of Shahrukh Khan and its overlaps with the production house. Yash Chopra, though best known for his romantic films, has had a career including some of the most iconic ‘angry young man’ films of Amitabh Bachchan including Deewar, Trishul and Kala Patthar (Ganti 2013). However, each of his films has spoken to the larger socio-political events and discourse of the times the films were made in, including his first film ‘Dhool ka Phool’ which tackled the issue of ‘illegitimacy’. In his engagement with Shahrukh Khan, Chopra made four films- Darr, Dil to Pagal Hain, Veer-Zarra and Jab Tak Hain Jaan. Apart from the films directed by Yash Chopra, Shahrukh has also had a long and sustained relationship with YRF including films directed by Aditya Chopra among others. These films include Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge, Mohabbatein and Rab Ne Bana di Jodi as well as Chak de India. All of these films have responded to the questions of their times in interesting ways. Especially in terms of Shahrukh Khan’s films, Chak de which speaks directly to the liminal relationship of the Muslim to the nation, in the figure of Kabir Khan, and his increasingly ‘Muslim’ presentation as Raees/Rizwan/Jehangir which is a massive shift from his Rahul/Raj avatars is worth noting. Playing Muslim characters and raising questions through their narratives on the increasingly fraught relationship between Muslims and the Nation is a trend in Shahrukh Khan’s films, whether a conscious choice on his part or not. In this context, Raees (2017) would be an important pre-cursor to consider for Pathaan as it was a major Shahrukh Khan film released in the context of ‘new’ Hindutva (Roy and Hansen 2022) which had him playing a Muslim man.

When one reviews SRK’s films and the political economy one finds a strange resonance. The 1980s was a decade which was marked by a struggle against the state’s policies and the failure of the state to deliver development, which kicked off major shifts in the political, economic, and social construction of India. This was also the decade in which the middle class emerged as a central socio-economic and political force in India (Fernandes 2006). The rise and accelerated presence of the middle class over the narrative of the nation since the 1990s became more predominant due to economic liberalisation. As Fernandes (2006) points out, Indian and global public discourses have focused on the size and economic force of India’s middle classes. SRK’s films and the characters he played have a strange resemblance to this changing narrative of the nation and its middle class. SRK’s films fall predominantly in the romantic genre which was always connected to the construction of the middle class. The nation’s narrative about who is its claimants and the sons of soil underwent a significant change, be it revisiting the restriction on foreign investment, or making borders and boundaries porous to facilitate the aspirations of the middle class. Films have been central to the making and popularizing the narrative of the nation and they highlighted the changing character of politics in India and the class which dominated the socio-political history of the nation.

In this context, it is interesting that SRK dominates the genre of films shot on foreign soil which strengthens the love for the ‘Bharat Mata’ and simultaneously addresses global Islamophobia with SRK increasingly cast as ‘Muslim’ in his reel life. This highlights the fact that directors, producers, and the actor himself weave their stories with what the nation is going through. It is interesting to note that on one hand when India was seemingly unaware of ‘same-sex love’ SRK had few shots about it though in a flippant manner, but underlining that this is something we need to recognize. But Post 2000 when the rivet of the majority community over the social and cultural landscape was holding on; major transformations were witnessed in India. SRK’s films have a complicated relationship with it because, on the one hand, his films strengthen the idea of a neo-liberal state and assimilate the aspirations of the new middle class and on the other complicate the rising power of fundamentalist / communal trend in India. However, it is interesting that till the ‘connection’ between ‘Fawad Khan’ and ‘love jihad’ was ‘discovered’, the ‘Khans’ in Bollywood were never identified as a threat. But in the recent past, as this narrative of love-jihad became popular and almost became a nationally important issue, SRK’s life and his films suddenly caught attention. As India became ‘Hindu’ India (Ludden 1996), SRK became ‘Muslim’. At this point, it is interesting to return to Pathaan with which we started because it is an average film, in terms of a cliched storyline, average visual effects and many pre-release controversies, including over a saffron bikini. Still, it was a huge hit at the box office and the audience was utterly in love with SRK, the screams, whistles, and wild applause he got on his first entry made us question whether we are living in completely ‘Hindu’ India or if there is still some hope. This hope is liminal, fractured, contentious, contradictory and ambiguous, much like the film and the persona of the star who makes it.

Fractured hope?

As both of us who identify as feminists and SRK fans, took this opportunity to look back at the socio-political history of the nation, cinema and SRK, we found ourselves holding on to a fractured hope. The challenge for us was methodological, about how not to read too much into SRK and his films but also not subsume it with(in) the narrative of the nation. This was challenging because our location and training in gender studies did not allow us to neglect the larger canvas and our attempt to engage with films as popular culture did not allow us to disregard the need to analyse films as independent sources. This exercise of reading Pathaan and understanding the contemporary narrative of the nation through that, landed us in a difficult situation, especially as feminists. On the one hand, the controversies around the film, including the colour of the bikini worn by Deepika Padukone, pushed us to support and invoke love for SRK, almost as a resistance to the right-wing majoritarian ideology. This is paradoxical for feminist sensibilities which would denounce the stereotypical presence and delusional heroism offered to women characters in films like Pathaan. But we ended by celebrating the success of the film at the box office by offering some setbacks to the success of Hindutva / right-wing politics. However, the subsequent success and discourse around the film Kerala Story has brought us back full circle to the entanglements of gender, sexuality, community, and nation. We would like to end this piece by referring to the current protest by women wrestlers regarding sexual harassment and the negative state and social response to it. This is indicative of the apathy we have as a society towards the woman question in general and the social anxieties around having to address the messy questions raised by embodied women. As long as they are devis/matas to be revered and worshipped, they have a place in the life of the nation. But when they emerge as embodied citizens demanding their right to full citizenship, they become threatening, ‘anti-national’ entities. SRK and his ‘Chak De’ are to be remembered here. The film underlines the establishment’s apathy towards women in sports paralleling what we are seeing today. But more importantly, in the context of the scene where their coach, ironically Kabir Khan, reminds them to think of themselves as belonging to the nation and not the region they come from. Even as the Muslim man can invoke the nation by asking for unity from women in service of it, we are forced to restate the question first raised by feminists in the context of the partition – Do women have a country? Or do they ‘only represent’ the honour of the nation, are they merely the ‘honey traps’ to be used for their sexuality by their nation? Even as we celebrate the limited success of Pathaan in providing a minor setback to the triumphant narrative of the Hindu right-wing, we must confront the very serious questions about the gendered nature of the nation and its intersection with caste, class region, gender and other axis of oppression.

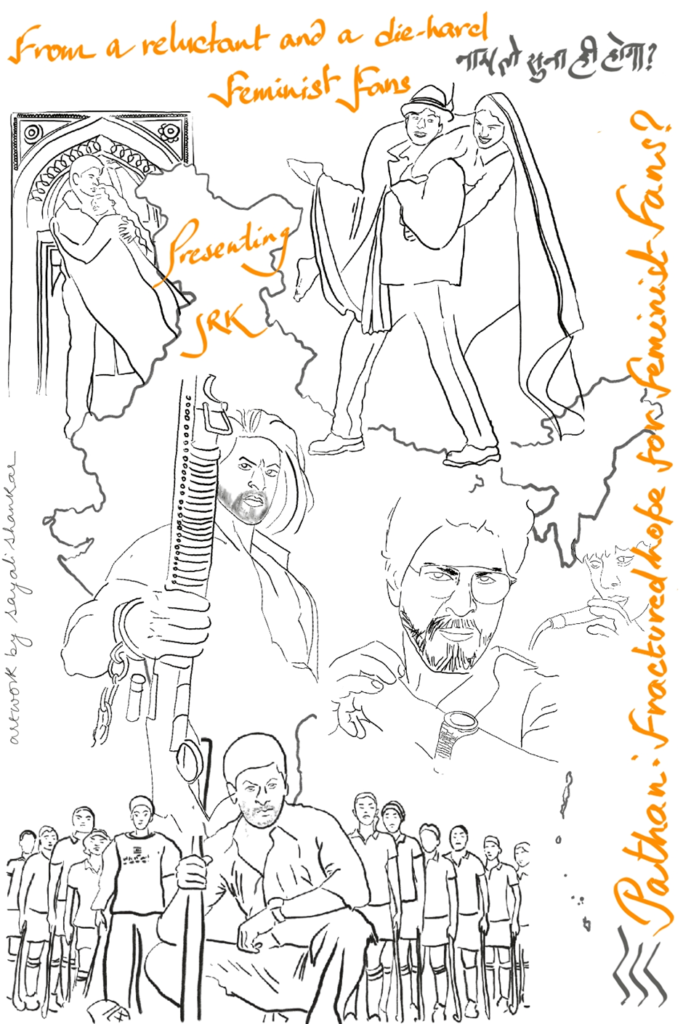

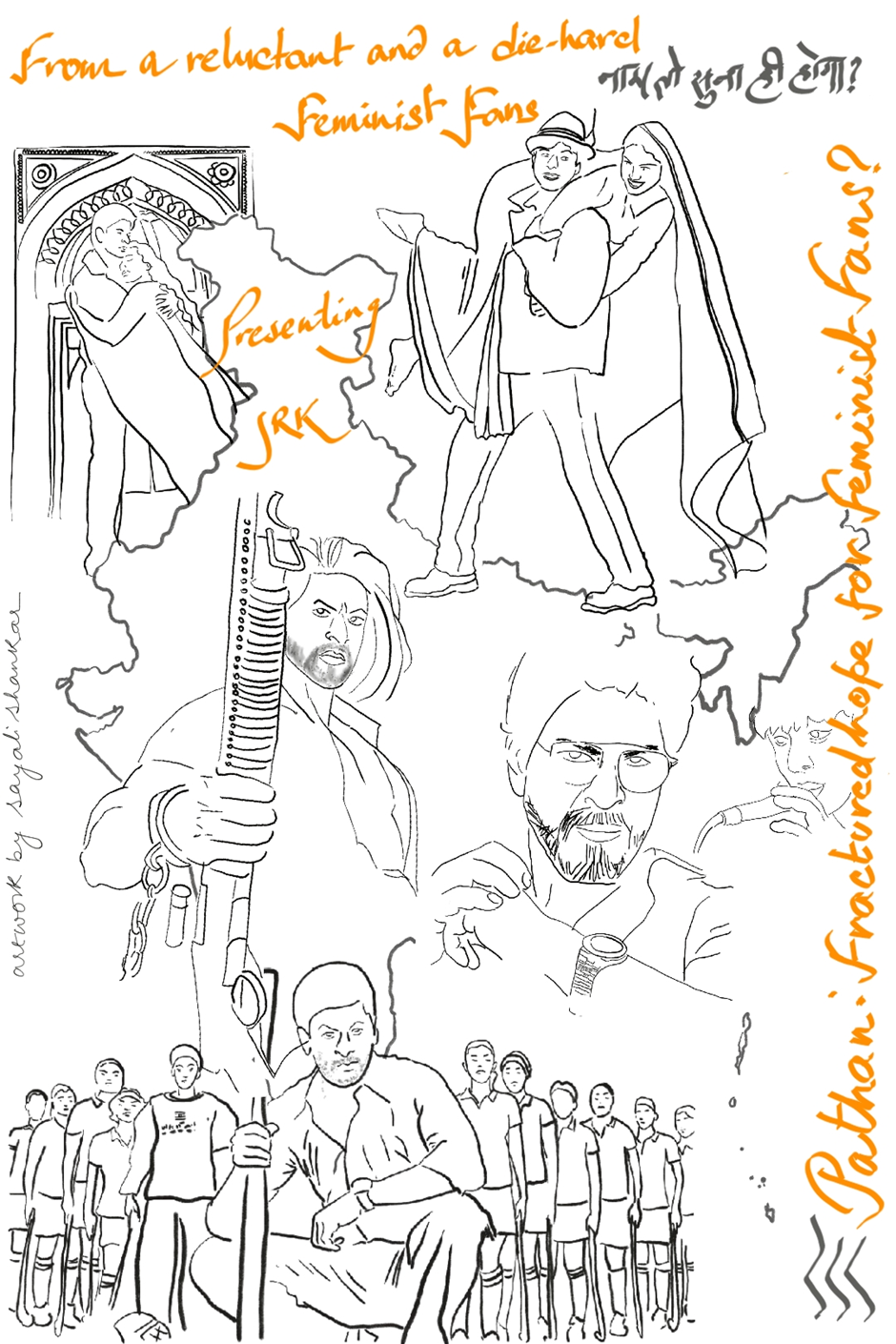

Acknowledgements: We would not have thought so much and exchanged so much about what it meant to be inter-generational and inter-dimensional 😉 (reluctant vs die-hard) fans and what we draw from the film and responses to it, had it not been for this wonderful community of people sharing ideas, stories and thoughts on Pathaan, brought together by Gita Chadha. Our immense gratitude to this critical and fun community – Pushpesh, Sayantan and Bishal, Deepa, Bindu, Rukmini, Gita and of course- Paromita who as someone said “humanized” Shahrukh for all of us! We also remain immensely grateful to Sayali Shankar for the smashing illustration she drew for us, which captures more than words what we have wanted to say!

References:

Dwyer, Rachel. 2002. Yash Chopra: Fifty Years in Indian Cinema. Mumbai: Roli Books.

Enloe, Cynthia.1990. Bananas, Beaches & Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics. Berkley: University of California Press.

Fernandes, Leela. 2015. India’s Middle Classes in Contemporary India in Routledge Handbook of Contemporary India edited by Knut A. Jacobsen. Routledge.

Ganti, Tejaswini. 2013. Bollywood: A Guidebook to Popular Hindi Cinema. London Routledge.

Hansen, Thomas and Roy, Srirupa. 2022. Saffron Republic: Hindu Nationalism and State Power in India. Cambridge University Press.

Iveković, Rada and Julie Mostov. (eds). 2002. From Gender to Nation. Zubaan: New Delhi.

Ludden, David. (ed). 1996. Contesting the Nation: Religion, Community and the Politics of Democracy in India. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

M. Madhava Prasad. 1998. Ideology of the Hindi Film: A Historical Construction. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Roy, Anuradha. 2020. The Gendered Nation: To be Recoded or Rejected in Women Speak Nation: Gender, Culture and Politics edited by Panchali Ray. Routledge: New York.

Virdi, Jyotika. 2003. The Cinematic Imagination: Indian Popular Films as Social History.New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Vitali, Valentina. 2008. Hindi Action Cinema: Industries, Narratives, Bodies, India. Oxford University Press.

Yuval Davis, Nira. 1997. Gender and Nation. London: Sage.

[i] Anuradha Roy, taking a review of the complex relationship of women with the nation, asks whether women should disown Nation/Nationalism altogether or have a different nationalism? She especially posits this as a question for third world feminists, as distinct from the internationalism of white feminism. She contends however that nationalism might have limited rights to offer to women and that an alignment between nationalism and feminism might be useful in limited ways, while calling for a transcendence from the national boundaries and borders.

[ii] I use the word ‘reluctant fan’ in an ironic way, not to distance myself from fandom, but rather to index the complex constellations of ideas that make for a caste-class-regionally refracted normative femininity. The reluctance is not in being a fan, but rather in owning up to the label, a process of unlearning and becoming ‘unlimited’ and ‘fearless’ (due credits to Paromita Vora and her film the ‘Unlimited Girls’). The characterization is also an invitation to think about the binaries of art/popular, emotional/rational, bodily/intellectual.

[iii] My name is Khan’ was addressing Islamophobia at the global level but the controversy related to the film in India which was started with SRK’s comments about why cricket players from Pakistan are not part of the IPL teams. This statement by him led Shiv Sena, Hindu Nationalist party to demand the ban on SRK’s film. This kind of censorship which was not new but indicates influence of the majority community over what we can or should watch. This censorship curtails our freedom to express our opinions and restricts opportunities to strengthen public debate / discussions voicing arguments critiquing the majoritarian perspective. SRK’s response to this criticism was also interesting where he was showing willingness to apologise but before that was asking for the clarification regarding what he needs to apologise for. Because the idea of IPL was completely commercial so he was indirectly challenging Islamophobia in India as well as how it is present everywhere.

***

Swati Dyahadroy is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Women and Gender Studies, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Pune. Sneha Gole is a Fulbright Post-doctoral Fellow and a Research Associate at Five Colleges Women’s Studies Research Centre, Amherst. She is on sabbatical from the Department of Women and Gender Studies, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Pune.

[…] Pathaan: Fractured Hope for Feminist Fans? – Swati Dyahadroy and Sneha Gole […]