Uday Berry’s nearly eleven-minute animated short film Bharat Minar. The Tower of a Forgotten India (2019) won the Best Fiction Short category at the 2021 Architectural Film Festival in London. The film festival “showcases the cross-pollination of architecture and filmmaking, exploring the evolving scope of each discipline”. Berry is a trained architect and graduated from the Bartlett School of Architecture (UCL) in 2019, where he was part of a project group (PG24) of architectural storytellers, led by Penelope Haralambidou and Michael Tite, which uses “film, animation, VR/AR and physical modelling techniques to explore architecture’s relationship with time” (Haralambidou & Tite 2023: 474).

As the short description of the film states,

“(e)xploring the politics behind architectural heritage, conservation and the state’s role as a custodian of culture, ‘The Tower of a Forgotten India’ follows the story of The Architect, a man desperately trying to save the nation’s past. A narrative of passion and madness unfolds within the Tower, a megastructure that reinvigorates forgotten buildings and fragments, reintegrating them into the city’s urban fabric. In India today threats to the country’s heritage come from every direction, including religious fundamentalism, thoughtless modernisation, the culture of collectability and political corruption – themes that this film closely examines. ‘The Tower of a Forgotten India’ is a modern parable spanning decades, suggesting that control of a city’s past is ultimately a fool’s paradise.”

This description leaves open which past epoch, the conception of the past/historical time and the architectural heritage belonging to it are specifically referred to in this fictional film. In the very first scenes of Bharat Minar, two different time and architectural levels are juxtaposed interestingly and visually linked accordingly: In minute 0:34min, we see Muslim men praying in front of a mosque that strongly resembles the Jama Masjid in Old Delhi and we are informed that the scene takes place in the year 2000. Above and immediately to the left of the mosque are construction cranes and a building still under construction, which is introduced as the titular Tower/Bharat Minar.

Still from the film Bharat Minar. The Tower of a Forgotten India.

At the moment when the first-person narrator begins to tell his story, we do not know yet that he is the white-haired and visibly agitated man in handcuffs awaiting interrogation by a police officer at the Old Delhi Police Station. The architecturally extremely interesting and light-as-air tower, we learn from this first-person narrator, was built at the time to provide a home for “threatened heritage” and the, “layers of history that the nation had simply forgotten (0:44min).”

Still from the film Bharat Minar. The Tower of a Forgotten India

Less than a minute later, the film narrative jumps to the year 2016 and we see that the construction of the tower is still not complete. At first, it seems that the first-person narrator might be referring to this tower when he speaks of a connection to “this building” that goes back to early childhood. But as the next scene reveals, he is referring to the Hall of Nations at the Pragati Maidan complex in Delhi and the film immediately makes another leap in time back to 1983.

Still from the film Bharat Minar. The Tower of a Forgotten India

As Mustansir Dalvi describes, the 1972 Hall of Nations, designed by architect Raj Rewal and structural engineer Mahendra Raj, was a “culmination of the Nehruvian era in Indian infrastructure building” and for decades an important symbol of “what we could achieve on our own in India (Dalvi 2017)”:

“That the halls were designed and analysed using computers, but drawn and detailed by hand, and constructed largely with manual labour, is a testimony to the Make in India spirit of that time, which extended the legacy of Nehruvian progress into the seventies. Exhibition venues in the latter half of the 20th century were great showcases of innovative architecture, just as the new museums are today. In the annals of modern architecture, this building was singular, much in the spirit of the Eiffel Tower (1887) or the Atomium in Brussels (1956) (ibid.).”

“In this photo taken on 02 November 1972 a group of visitors posing for a photograph at Pragati Maidan during Asia ‘72 Exhibition.” Virendra Praphakar/HT File Photo. https://www.hindustantimes.com/photos/india-news/in-pictures-pragati-maidan-in-the-process-of-a-historic-facelift/photo-2Op1RTgsLa8IohhME20FrL-1.html

“In this photo taken on 19 July 1972 women labourers and their children visit a function organized by the Trade Fair Authority of India in honour of construction workers and their families who worked day and night to construct the exhibition grounds for the Asiad ‘72, an international exhibition for various participating countries across the globe” KK Chawla/HT File Photo. https://www.hindustantimes.com/photos/india-news/in-pictures-pragati-maidan-in-the-process-of-a-historic-facelift/photo-2Op1RTgsLa8IohhME20FrL.html

As the largest continuous exhibition hall in India, the iconic structure has been closely associated with major recurring exhibition events such as the International Trade Fair, Auto Expo and the World Book Fair, which has also given it a very special place in the popular imagination, as Dalvi also points out (ibid.).

Exactly this feeling is conveyed by the very short sequences from the film’s flashback to 1983, apparently the childhood years of the first-person narrator, in which we see families visiting the Hindustan Aeronautics Expo in the Hall of Nations and an altogether bustling trade fair scene open to visitors in beautiful weather.

Still from the film Bharat Minar. The Tower of a Forgotten India

The dynamic and at the same time acoustically cheerful scene is immediately overturned, however, because we now experience in a kind of live simulation how this very Hall of Nations is razed to the ground in 2016 under darkened skies and rain. The first-person narrator describes this destruction of the building as a “crime” and then explains that his team had the task of dismantling the remaining individual parts of the outer façade and then transporting them on trucks to the tower at night and in the rain.

Still from the film Bharat Minar. The Tower of a Forgotten India

Still from the film Bharat Minar. The Tower of a Forgotten India

We now also learn that the first-person narrator, as a young architect in an architect’s studio in the middle of the Tower at the time, was entrusted with the task of preserving the remains of the Hall of Nations.

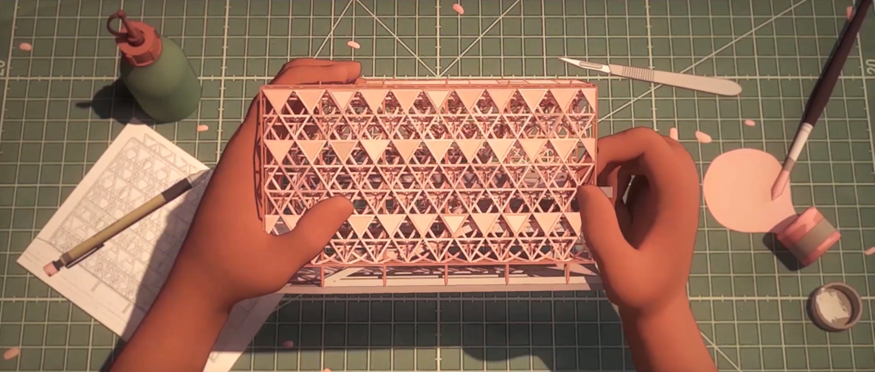

Still from the film Bharat Minar. The Tower of a Forgotten India In an interesting overlap of model and ‘reality’, from minute 03:30 we leap into the year 2020 of the film’s plot and see a hand – the architect’s hand? – carefully removing a miniature replica of the Shri Centre for Performing Arts from the Tower, another significant building from the period (1968-72), which the same structural engineer Mahendra Raj had realised – this time in a “pas de deux” with the architect Shiv Nath Prasad.[i] In its place, the reconstructed/restored Hall of Nations is now inserted into the tower. As viewers, we now understand that Uday Berry’s film addresses primarily the ‘recent’ past and the question of what significance is attached to the architectural heritage of this period for post-colonial Indian history as well as the process of identity building.

Still from the film Bharat Minar. The Tower of a Forgotten India

Still from the film Bharat Minar. The Tower of a Forgotten India

As the destruction of the Hall of Nations is already classified as a “crime” by the architect and first-person narrator at the very beginning of Uday Berry’s film, Bharat Minar takes a clear position in the debate on the issue and in no way follows the view of the Delhi High Court, which, in response to an urgent appeal for the preservation of the iconic building stated (with reference to a statement to by Delhi’s Heritage Conservation Committee) that buildings younger than sixty years could not be given the status of architectural or cultural heritage (Dalvi 2017).

A very paradoxical explanation, because we talk about ‘contemporary history’ and a ‘recent past’ with a view to the post-WWII and first phase of decolonisation, which exerted a strong influence on the social and political orders of the post-war era that emerged from it.

“Thus, every possible contemporary Indian construct from living memory, even a monument of national importance, let alone a structure acclaimed worldwide by peers in the architectural and civil engineering fraternity, has potentially been condemned to dust. Within hours of the ruling, in the dead of a Sunday night, the India Trade Promotion Organisation, which is part of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, brought the structure down (…). The loss of the Hall of Nations will always be deeply felt as it marked when it was built, a point in the history of modernity in our nation-state (Dalvi 2017).”

Back to the film plot in Uday Berry’s film Bharat Minar. The memory and report of the imprisoned architect are now focused on the rise to power of a political leader in 2020, by which the secular ideals of society are being destroyed while he is in the process of building his Hindu nation. We see this politician entering the Tower with much pomp and being cheered by an exclusively male as well as highly emotionally charged audience.

Still from the film Bharat Minar. The Tower of a Forgotten India

He begins to agitate against the Tower or rather, against the work of the architects in restoring the remains of the Hall of Nations and thereby preserving a collective memory of the architectural heritage from the ‘recent past’ of independent India. All this is now, in the fictitious year 2020 of the film, being branded as ‘un-Indian’ by the Hindu nationalist party and its supporters.

The salvaged fragments of the destroyed buildings are then covered and sealed, and the architectural office itself is also closed by the authorities, to the horror and despite vehement resistance of the employees. The narrating architect recounts how he tried in vain to stop the imminent destruction of the Tower (Bharat Minar) through public debate.

Still from the film Bharat Minar. The Tower of a Forgotten India

Still from the film Bharat Minar. The Tower of a Forgotten India

In minute 05:42, we look over the shoulder of a male newspaper reader at an edition of the English-language daily newspaper The Times of India, dated 27 May 2042, another twenty years later. The headline of the front page story reads “V&A Acquires Bharat Minar Fragment”, from which we learn that as a result of an agitation against the tower over many years to preserve the architectural heritage of the ‘concrete era’, which stood for a different ideal and an inclusive identity of post-independent Indian society, it did end up being destroyed. The irony of preserving the remains in one of the most important museums in the capital of the former colonial power, Great Britain, is remarkable. But all this only further incited the fierce rejection of the Tower by the ruling party and its supporters, as we learn from the first-person narrator.

Only pausing on the computer allows a closer look at the actual content of the ToI cover story depicted in this scene, which might be rather difficult to grasp during a live screening of the film Bharat Minar: what the article projected into the future describes is the 2016 destruction of the Hall of Nations.

Still from the film Bharat Minar. The Tower of a Forgotten India

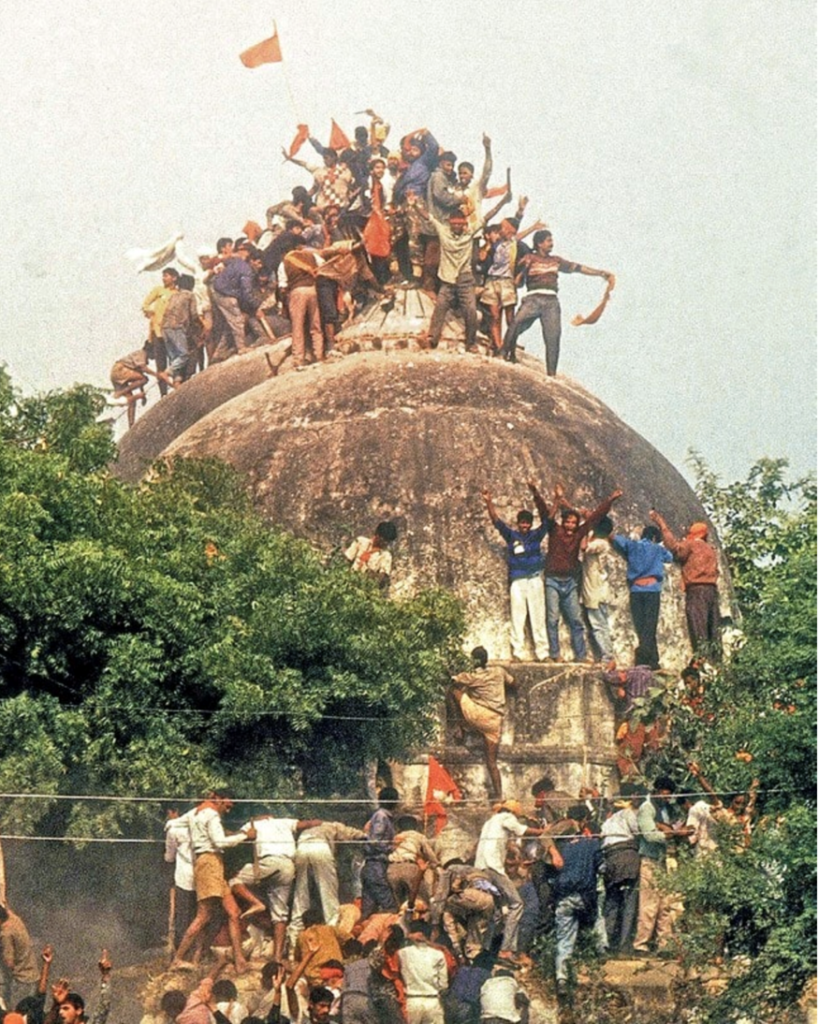

From minute six, in which we see an angry crowd of Hindu nationalist activists storming and destroying the Tower, another interesting conflation of different temporal levels and layers of Indian architecture and the mediatised memory of its destruction takes place. What the scene strongly reminds us of visually are the widely circulated photographs showing triumphant gestures of Hindu nationalist activists after the storming and destruction of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya on 06 December 1992.

Still from the film Bharat Minar. The Tower of a Forgotten India

https://www.reddit.com/media?url=https%3A%2F%2Fi.redd.it%2Fon-this-day-in-1992-a-large-number-of-religious-volunteers-v0-e6676x2g2b4a1.jpg%3Fs%3Dba4988e976e67ccbfadc9a81b18112126ea0fdd5&rdt=65529

For the architect, this critical event marks a dramatic turning point and the destruction of the buildings symbolises for him the collapse of what he saw as the foundations of the independent Indian nation. We see him running barefoot and bare-chested through a street in nightmarish visions, while buildings from different eras shatter in the background. For him, there is only one politically responsible person and he seeks retribution. In the end, he makes his decision and carries out the deadly assassination of the Hindu nationalist politician.

At the end of Uday Berry’s fictional short film, we return to the beginning and starting point of the architect’s narrative and understand that it was his account in the context of the interrogation by the police officer at the Old Delhi Police Station.

The architect does not hope for understanding for his deed and nevertheless ends his account from minute 09:20 onwards with an appeal to his audience, or an imagined public, which he nevertheless assumes still has the capacity for critical reflection and discussion when he says:

“As Delhi is reconstructed in the state’s vision of world-class, our heritage is forgone to make way for a new nation. Contemporary India is once again forced to ask the question – what does it mean to be Indian (the original Hindi version uses „asli hindustani“ in this sentence)?”

On 7 and 8 August 2023, the India International Centre in Delhi screened both parts of the 2017 documentary film Indian Modernity – The Architecture of Raj Rewal, directed by Raj Rewal’s son Manu Rewal, in the presence of the director. The timing was certainly deliberate and understood by the film’s audience, as can be seen from a comment by Facebook user Le Corbusier in India: “Sad to see the Hall of Nations in the week that ‘Bharat Mandapam’ was inaugurated by priests and havans.”

Bharat Mandapam, the new venue for the International Exhibition-cum-Convention Centre (IECC), for the construction of which the Hall of Nations and everything that the Pragati Maidan of earlier decades symbolically stood for had to make way, has been celebrated in recent weeks with great media effort as a new ‘architectural marvel’ and will soon stage the self-confidence of the ‘new India’ for a global media audience on the occasion of the mega-event of the G 20 Summit in September 2023.

Critical architects not only criticise the new IECC complex but also pose the question of how the Indian state and current government view the role of architects in this special year of ‘Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav’ – the 75th anniversary of India’s independence. The architect Kavas Kapadia puts it as follows:

“The Government views the status of the profession as a commodity that must fit into the political calendar. If Norman Foster is to be believed, then ‚architecture is an expression of values.‘ And what is the new complex expressing?”

He also points to a particular form of bureaucratic and patronising attitude towards architects as well as architectural educational institutions:

“Architecture as a profession has been taken for granted for far too long in India. Not getting its due recognition even after 70 years of independence is due to a lot of reasons, but especially in a society where the official recognition is subject to the bureaucratic whims and fancies of those who know it all, it has been harmful.

When the architecture juries, selection committees, even design committees, and academic and executive committees in the schools of architecture are headed and scrutinised by bureaucrats, it begins to show. They tell us what is ‘world-class’ and what is the next big project. Good is confused with big. The biggest statue in the world, the biggest stadium in the world, and the promise of bigger things to come with zero intervention of specialists and experts (Kapadia 2023).”

In his film Bharat Minar – The Tower of a Forgotten India, Uday Berry uses the exciting possibilities of architectural storytelling in his chosen format of an animated fictional short film to reflect on these complex questions and link them to different conceptions of historical time. In a certain way, his film also “plays” with the different notions and levels of time and memory which, given the jumps between different decades as well as the creative placing of (historical) events in the past, present or future, can also cause confusion and is possibly intended to do so. To what extent the architect’s assassination of the Hindu nationalist politician seems remotely plausible or was ‘necessary’ for what the film would have managed to convey very well without it is another question. Nevertheless, the narrative construction and fascinating artistic realisation show the potential of visual architectural storytelling as an emerging form that will hopefully continue to thrive in the coming years and gain much more interest.

[i] Martino Stierli describes the close collaboration between architects and structural engineers, which was necessary for the formal resolution of the Hall of Nations and “many of India’s concrete buildings during these decades” (Stierli 2022:17), as a pas de deux. Mahendra Raj also worked with other well-known architects such as B.V. Doshi and Charles Correa, among others. This collaboration resulted in other famous buildings that Stierli calls “the most iconic structures of post-Independence modern architecture in India” (ibid.)”. Martino Stierli (2022). The Politics of Concrete: Industry, Craft, and Labor in the Modern Architecture of South Asia. In: Martino Stierli/Anoma Pieris & Sean Anderson (eds.) The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947-1985. New York: The Museum of Modern Art.

***

Nadja-Christina Schneider is currently a professor of Gender and Media Studies for the South Asian Region (GAMS) at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Her research interests include media, cultural and urban studies; gendered im/mobilities and intersectionality, as well as secularism and religion.

[…] Read the whole essay on Doing Sociology […]