Women are a quintessential part of the horror movie trope. From being the infamous ‘damsel in distress’ to ‘scream queens’ to rising into the ‘final girls’. Female characters have gone through revolutionary changes in the cinematic history of horror. This article traces the famous tropes in a horror movie and how the representation of women has evolved.

The Damsel in Distress

Cinema mirrors the reflection of the society in which we live, as a result, horror movie tropes for the longest time have been laced with the male gaze. Early horror movies saw portrayals of the infamous ‘damsel in distress’. The stereotypical character of a ‘damsel in distress’ consists of a woman, typically a white blonde woman, who is young and beautiful and often caught in a crisis. A classic example of this is the character of Marion from Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, Marion is a conventional damsel who dies within 30 minutes of the film. She is a young white woman, who is vulnerable and helpless. To appeal to the audience the damsel is usually over-sexualised, exploited and at all times portrayed by a cis hetero white woman. The typification of a ‘damsel in distress’ as explained by Hitchcock himself can be owed to merely her looks.

“Blondes make the best victims. They’re like virgin snow that shows up the bloody footprints” – Hitchcock.

Cinema reinforces the stereotypes regarding the vulnerability of women purely based on their looks. We can also observe that women of colour rarely have been depicted as damsels as they are ‘supposed’ to be strong and self-reliant, hence the audience fails to connect with black women victims. As Cynthia Nicole White quotes, ‘the strong Black women stereotype consists of three factors: mask of strength, self-reliance/strength, and caretaking. Mask of strength refers to emotional invulnerability and hiding one’s struggles, Self-reliance/strength is the practice of trying to be strong and self-sufficient, and caretaking is the act of caring for others and emphasises helping others.’

The Final Girl

However, over the years the damsel trope has withered away and been replaced by the ‘final girl’. In simple words, a final girl is the last woman standing. Unlike the damsel, she survives till the very end owing to her wit and intelligence. She is smart, aware and not afraid to use violence as a means to protect herself. However, the major problem lies in the fact that a final girl is supposed to be a quintessential ‘good girl’ who is viewed as a virgin and whose sexuality is highly repressed. Throughout history, women’s sexuality has been subjected to taboos and oppression. Horror movies take advantage of this and often depict the ‘final girl’ as a pure virginal girl. Virginity is equated with purity and a great survival instinct in these characters. In contrast to the final girl stands the sexually active friend or the side character, who dies during the film because of her ‘sexual deviations’. Movies such as Halloween, Scream and Texas chainsaw massacre are a few such movies to glorify the themes of the final girl.

Bollywood

Bollywood movies for the longest time catered to the sexist tropes in horror movies. In the 2002 movie, Raaz there exists a clear demarcation between the ‘good’ and the ‘bad’ women. The protagonist or the ‘good woman’ is a caring wife, who will do anything to protect her unfaithful husband who is haunted by the spirit of a woman with whom he had an affair. The ‘other’ woman is portrayed as an evil spirit who wreaks havoc in the life of the married couple. The film villainized the ‘other’ women and victimised the unfaithful man reinforcing the idea of misogyny and dutifulness of a married woman. The duty of a married woman is portrayed as the utmost responsibility of a woman disregarding the unfaithfulness of the husband.

However, in recent times films such as Bulbul and Stree have broken the barriers of the stereotypical framework of age-old concepts of a daayan or chudail. Bubul tackles sensitive social issues of child marriage, violence and power, incorporating it with horror. It presents a reformed image of an age-old mythical ‘chudail’ who over the years has been understood as an evil woman who lures vulnerable men to bring upon them havoc and wrath. However, in Bulbul a chudail is a woman who has been wronged by society and seeks revenge on her wrongdoers by taking advantage of the very superstitions surrounding women.

What Is Next For The Women In Horror?

Men have predominantly occupied the hegemonic position as actors, directors and screenwriters, as a result, we have for the longest time seen cinema of men, for men, by men. Charles Horton Cooley coined the term looking glass self which implies ‘we few ourselves as we believe others would view us’. Girls are raised with a strong perception of themselves that stems from a Male gaze. Women have thus internalised the hegemony of men towards how they view the world as well as themselves. Hence it is more fitting for the audience to watch a woman in distress and scared on screen than men.

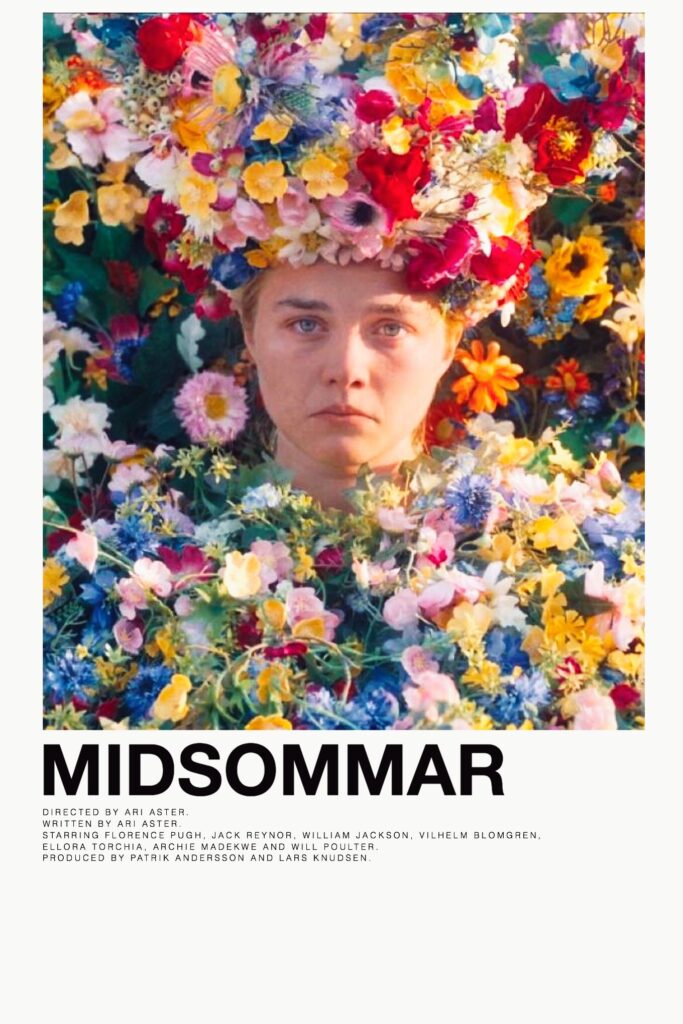

Horror movies over the decade have gone through genre change transforming into female characters with more depth and nuances. Movies such as Midsommar, the Witch, the Invisible Man and Ready or Not depict women in a new and reformed light. The Witch follows the story of Thomasin, a young girl from a conservative Puritan family. Being a young woman from a hyper-religious family, Thomasin is blamed for being a witch when misfortune befalls upon the family which forces Thomasin to ultimately find the liberation of her body and choices upon becoming a witch. The movie captures the experience of a young woman as she embraces her sexuality breaking away from the shackles of religion. Again, we see a dichotomy drawn between sexuality and religion, where the sexuality of a woman is seen as satanic, and dangerous, in contrast, stands the morality of religion which aims to control and repressive the sexuality of women.

Conclusion

The horror genre by far stands as a powerful medium of storytelling. Even though movies largely suffer from what the late journalist Gwen Ifill explained as the “Missing White Woman Syndrome”, it refers to the media’s fascination with and detailed coverage of the cases of missing or endangered white women – compared to the seeming disinterest in covering the disappearances of people of colour. Horror movies are yet to capture the experience of women of colour, transgender and non-binary experiences. It is a long battle for horror fans to find the right representation through the art of storytelling.

***

Prakriti Kandwal graduated recently from Hindu College with a BA (H) in Sociology. She has a keen interest in gender politics and cinema studies.