This piece delves into an intergenerational fandom, and its influence on me as a Shah Rukh Khan fan. Be it with my grandmother, my aunt, or my larger family, our love for him is not limited to the affective emotion, but extends politically. A lot of our feelings around SRK encapsulate our feelings around politics. Being in love with him has not just made me see him as an actor, but rather in a political light. Be it my grandmother perceiving him as the nation’s son, or him being depicted as the greatest lover on screen, to love Shah Rukh is also tied to his political self. Being part of informal conversations around him, his actions are always politicised, where he is either doing nothing or a little too much. I have grown up feeling that to look at Shah Rukh has always meant looking at him through a political lens. Hence, be it Shah Rukh, fandom, or his movies, my engagement with him cannot be devoid of politics; a centrality explored in my writing.

Part I: First Impressions

My first introduction to Shah Rukh Khan was watching a pirated copy of Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham (2021, Dir: Karan Johar) while holidaying with my parents in the jungles of Madhya Pradesh. Barely three years old, I uncannily remember him as Rahul wooing Anjali (played by Kajol), blushing and gushing about his charms, and those expressive eyes. I cried with him, and the rest was history. The characters from the movie, ever larger than life, instantly became a part of my playtime. While I played with my soft toys, they would help me take care of them. Our dear hero’s job would be to make warm milk for them, as my mother reminds the whole family regularly with me red-faced.

Films have played a predominant role in my life. Along with books, they reinforced the imagery of world-building and the land of stories in my mind. Shah Rukh was my best friend, my close confidante, as fictional characters often become. I think that’s how fandom builds, we all build worlds around our heroes, fictionalising them subjectively, just a few tweaks here and there, depending from person to person. I realised this even more as my Shah Rukh clashed with another in the household, that of my grandmother. I remember being annoyed to see her claim herself as the biggest fan in the house. “I have known him for longer, even before you were born”, she would smirk at me. Her only regret is that she missed sharing his birth date by five days. My grandmother and I would go for every movie, and sit next to each other even as we watched one of his movies on television. We love cricket, so you can imagine our excitement and glee when he announced his very own team – the Kolkata Knight Riders (KKR) for the Indian Premier League (IPL), where else, but in Kolkata. “He is going to be so close to us”, we would think. It felt like he was just a bit more ours now.

The Kolkata Knight Riders never reached the playoffs from 2008 to 2011. With the team re-shuffled and re-organised, and a controversial decision to leave a few players behind, the new KKR team in 2012 made it to the play-offs, satiating many angry Calcuttans at that time. I didn’t think much about it, only fourteen at the time. But it was when I read an article my grandmother wrote that I first felt his influence and undeniable strength and power. Living with Multiple Sclerosis ever since she was forty years old, she has been self-motivated, undertaking physiotherapy, exercising in her free time, and continuing teaching as an English Professor, specialising in the Romantics. A blow to her mental strength came in 2012 as a series of minor strokes in her brain, small enough to look ordinary from the outside, changed her actions and cognition, bit by bit. With doctors calling it inevitable, with little scope for recovery, there seemed to be little hope. She would talk often of Shah Rukh, beaming whenever she would catch a glimpse of a music video from one of his movies, or even an advertisement. “He’s going to come to our house, we need to place a few more plates”, she told me one day as we sat for dinner. I told her, “I don’t think he can come today, see, the match is going on. He’s in Eden Gardens.” She replied with a smile on her face, “Oh, but he always keeps his word. You just see he will come.”

She made it past the cloudy haze of uncertainties, nonetheless, writing an article about how Shah Rukh brought her back to herself and inspired her to keep fighting. Writing about the second season of IPL held in South Africa, and KKR in the last position in that edition, she wrote about how he didn’t give up and rebuilt his team, ignoring judgement but just believing in change that was required, even if radical, going against fan-favourites. And oh did the team deliver! “If Shah Rukh can take a team, that everyone had lost their hopes in, and turn it around like this, I can do it too!” I cried that night, apologising to her for being a brat, because I had no idea about the depth of any fandom. “You are a much bigger fan than I could ever be”, I told her. She only laughed and consoled me as I kept crying. That was the day that cemented my love for Shah Rukh Khan, the person, in every which way he is.

I am grateful for growing up around people who loved Shah Rukh. Be it friends or family. So much so, that being his fan, his admirer, felt almost natural, with celebrations around his fandom needing no hiding. But it was when I met my aunt that I again felt the magic of Shah Rukh. Not only was she an admirer, their birth dates were the same, she had told me, beaming. I remember my grandmother telling my aunt with glee how happy she was, almost like my aunt had fulfilled a dream that she had longed for. Be it November 2nd or the 7th, their love and adoration for each other and their favourite actor was heartwarming. The closest I have ever felt to Shah Rukh, I would listen to how my aunt found him through newspapers, television, and above all, music. “His movies weren’t just doing well at that time, but they also had really good songs, soulful and catchy. That often made it easier for me to convince my family to go watch one of his movies, or buy the film’s cassette”, she shared with me. Looking back at the 2000s, and growing up as his fan myself, her statement resonated with me beyond a doubt.

If falling in love were as easy as he made it out to be, or so it seemed as a child, it wasn’t just tied to him, but through everyone who loved him, reaching out to him in a vast interconnection of threads, a bond so complicated yet tight, that he was a part of our lives, our discussions, and our reasoning. Given time, I would grow up to find myself distancing myself from many themes in his movies. Academically engaging too had turned out to be political after all. “Was it ever possible to segregate the personal from the political?” I wondered as the seemingly growing distance still didn’t permit the thread to weaken, and I remained somewhat knitted in that bond, maybe not as happy as I was a decade back. Somehow the same happened with my aunt, the distance was perhaps wider, and she could not pinpoint why. Was the magic fading away? No, she would always love him, she said. And amidst it all, there she was, my grandmother, awaiting the return of her almost mythical son – laughing in joy as she watched his movies on TV. Dementia slowly took a stronger hold over her along with depression, I watched her distance herself from the complicated reality of life, smiling for him as he smiled on the small screen. And there it was, like magic as if everlasting. So began the wait, to feel it again, waiting for his return to the big screen, ready.

Part II: The Comeback

Pathaan (directed by Siddharth Anand) was released in theatres globally on 25th January 2023. Controversies around ‘besharam rang’ aside, the movie was meant to be our hero’s big comeback. Here, I don’t refer to the ‘comeback’ as a term connoting one’s reemergence from a has-been to a celebrity (NBC News, 2010). Rather, my expression of a comeback is similar to its usage in the K-Pop industry – a new song/album from a singer/band after a period of hiatus (it can be a few months or a couple of years) where the singer/band didn’t release any music (Bennet, 2021). According to a 2023 report by Ormax Media, 2022 saw only 122 million movie-watchers in the theatre, compared to 146 million between January to March 2020 (Ambwani, 2023). Coming back on screens as the lead after four years, with a lull in movie-watching in the post-pandemic world, one could trust our hero to bring back the excitement and the fun for the masses, breaking away from the single screens in our households, to so many single screen movie halls, and multiplexes, globally.

I was excited to be in Mumbai on that day, as the last time I was in the city, in October 2021, I watched the sunset while sitting in Bandstand with my mother and my aunt, silently. “They have arrested his son”, my father called to inform us, as we were still in the process of comprehending the unfolding situation. It was the first time, in my tradition of visiting the Bandstand and the gates of Mannat, that I felt a sense of hopelessness and loss. My learnings have helped me both understand and criticise his movies and his characters. I believed I had “grown up”, and was not so rooted in the fandom. Yet, I felt broken and angry. I didn’t have words to express what I was feeling or to understand it either. But Shrayana Bhattacharya did. Her book, Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh Khan: India’s Lonely Young Women and the Search for Intimacy and Independence (published by HarperCollins India) in November 2021, brought this student of gender, buried in assignments and academic papers, closer to understanding women, the country, and the fandom, in the most approachable way.

I was only able to watch the movie in mid-February. By that time, I had already received an overdose of excitement and judgement from fans and critics alike, personally, as well as over social media. But walking into a multiplex in Kolkata, with an audience, many of whom were rewatching Pathaan, I went back in time to stories my grandparents told me about watching Sholay. The audience screamed the dialogues, whistled and cheered, jumped in joy and danced. They laughed, they cried, and how much they clapped. Sorry. We laughed and cried, and clapped so much, especially in joy. “He is back”, my aunt smiled as her eyes glistened, and we cheered. It was a celebration, far away from the prude-ish eyes that looked down at this behaviour. It was joy, love, and camaraderie. “Pardon the occasionally ‘cringe’ dialogues. You’re watching a Shah Rukh Khan film, and he’s for everyone, not just the woke”, is what I wrote while reviewing the movie. I think I could have ended it right there.

But, I was too interested in how Aditya Chopra got all the points and created an imperfect movie that hit the heart. If someone told me that they were creating a Hindi “masala” film with two songs, I would have probably laughed it off. But, they did. If you asked about hyper-nationalism, I would tell you that the movie goes back to the roots of the Pathaans in Afghan, whose descendants form a crux of the Indian Muslim community, thereby tracing a beautiful history of lineage, paying them homage as the titular character finds a family in them. And it forms the crux of his identity, in addition to him being an Indian soldier. He is shown to be patriotic, but he understands Jim’s declaration of war. He is emotional, he listens to his heart, and he criticises his superiors and the government by no means of disrespect; everything that we, the common people, are being taught not to do. While theorising masculinities, Connell writes about the term “hegemonic masculinities” to connote the most desired way of being a man, based on which all other masculinities were positioned, and that legitimised women’s subordination to men (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). I was confused. Did Pathaan’s hegemonic masculinity influenced also by military masculinity not come in direct conflict with the Pathaan who relied on his emotions, even if that ended up costing him a betrayal? Reading Pushpesh Kumar’s article ‘Pathaan, Military Masculinity and the Possibility of a Queer Reading’ (2023), made me realise the way ambiguities of Pathaan’s identity extended, and was open to interpretation. One resolute self stood above others, in clear confirmation – his identity as an Indian, and his patriotism.

From that standpoint, when Pathaan said, “A soldier doesn’t ask what their country has done for them, but asks what they can do for their country”, one can argue that this statement can extend beyond military duty. It reminded me of our fundamental duties as a citizen, and to stand up for what we believe in, especially when secularity, identities, and our diversity is threatened, be it externally or internally. The idealistic romantic in Pathaan strikes me and resonates with the idealistic romantic in me because it goes beyond the concept of Mother India. Yet they evoke the same imagery. The last time they did, our ancestors were struggling to unify this country and fight colonialism. Unity is difficult when there are rampant efforts to destroy it from within. Intolerances rise rapidly when despots have control, but despots can be brought down too. Pathaan boldly takes on the distinction between patriotism and nationalism, the former extending beyond military expression, devoid of jingoism. Pathaan may not have sub-identities, but that privilege doesn’t extend to everyone, especially in a country obsessed with labels.

And so, as the movie ended and we dispersed with smiles on our faces, I couldn’t help but wonder, is my understanding of this movie just a healing balm meant to delude myself and hope? Is this a way for me to hold our hero up on a pedestal yet again as if he were our champion? It couldn’t be just me, right? As Dyahadroy and Gole (2023) argue about a feminist’s fractured hope in holding on to Shah Rukh through Pathaan providing the dominant narrative of the Hindu right-wing only a minor setback, I knew I wasn’t alone. But it was at that moment that I recalled the people I watched the movie with, dancing, laughing, cheering for our hero, clapping, crying – an emotionally charged atmosphere complete with people from different religions and sociocultural identities. Maybe this victory wouldn’t be short-lived, but one can’t help but hold on to that hope- the hope that Shah Rukh has always instilled in us – that one must keep striving, and keep believing, that happy endings do exist. For the moment, it would seem that his return to the big screen would suffice (Manil, 2023). I envied my grandmother and her life beyond the grips of social media. I only wished she could see him too, and know that she was right – he always keeps his word; the prodigal son had indeed returned.

Part III: Still Jawan at 58

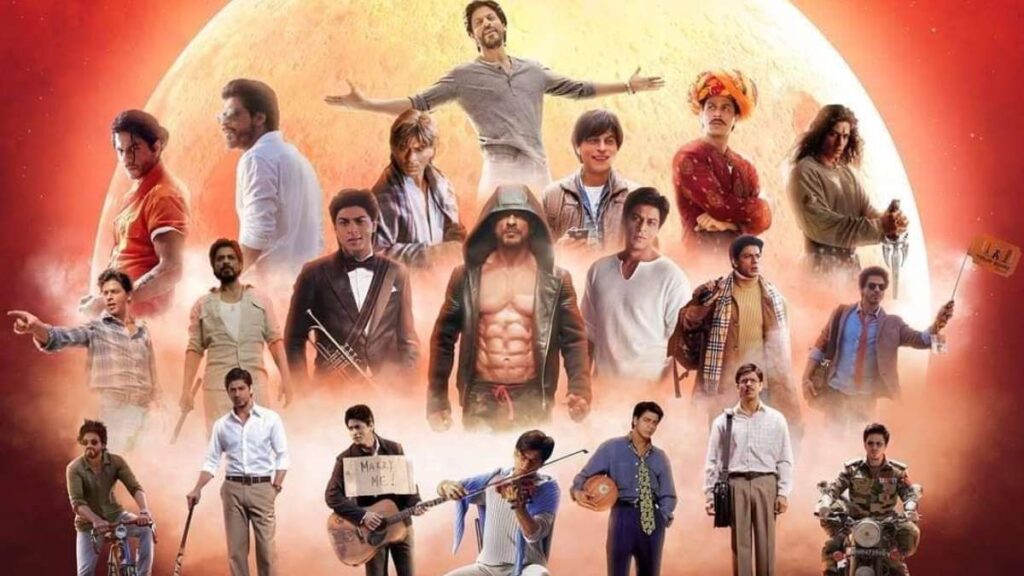

If Pathaan set the stage for the return of the king on the big screen, Jawan (2023)directed by Atlee, set the stage on fire, burning the pedestal, and placing our hero right amongst us. Social media posts raged as quotes from Nolan’s The Dark Knight (2008) were placed next to his image. “He is the hero we need, but do not deserve.” The Champion of the people, for the people, by the people, time and again, Shah Rukh Khan comes to the screen, as Mohan Bhargav, Kabir Khan, Rizwan Khan, Pathaan, and now, embodying freedom himself as Azad. Movies have time and again played a vital role in India’s culture, be it as a lens to view the country, or in inspiring new traditions. One of the first things I learnt when I joined as a Qualitative Market Researcher, was that Indians are apparently ‘emotional consumers’. We connect via our emotions, be it with brands, movies, or people. So, when digital overconsumption has fried our brains with a numbing information overload and a constant pleasure-seeking dopamine hit (Waters, 2021), Atlee creates a movie for everyone, that’ll not just deliver entertainment, but force people to look reality in the eye while representing people’s struggles.

“It reminded me of the Shah Rukh I would see in the interviews. Eloquent and loving, yet knowing his influence always”, my aunt said on our way home after watching Jawan. A Shah Rukh fan since she first saw him in Fauji, she would tell me about how watching movies was a privilege: “My parents would only take us out, once in a while, that too if a good movie had been released. It helped that Shah Rukh was different, and always stood out, making good movies. It felt like he was exactly like us – entering a filmy world, and working his way to the top of the world! An entire generation was charmed and inspired by a man who was set on making his way to our hearts”, she told me. And there he was, breaking his silence, laying his feelings bare, toeing no party line, talking about the people, urging us to ask questions, as Azad. Upon returning home, I told my grandmother that Shah Rukh Khan was back again, his second movie of the year. She looked at me a bit quizzically. “Babi, you remember Shah Rukh, na?” I asked, quickly showing her my phone screen with his image on it. Immediately, her lips sealed tight to form a hard smile, and with sternness in her eyes she nodded saying a very loud, “Hmmm!”. I laughed and apologised, continuing to regale her with the plot of the movie, and what people were saying. I don’t think what people said mattered to her, for she was in a few moments grinning wildly and laughing again. It had been a few years since we had regaled overjoyed as happy fans. And despite not speaking, her wide-eyed smile conveyed everything in a moment. She too was missing him.

Critics will ask whether we are truly naive enough to believe it to be Shah Rukh himself, after all, it was Azad. I’ll frankly say that I don’t know. All of us have our association with him, and we have each built our interpretation and our own story around him. We rarely talk about the person that he is, even if we think we are, for there are multiplicities in who he is. At 25, 43, and 80, we have engaged with Shah Rukh Khan through a significant portion of our lives in starkly different ways. For my grandmother, he is like a son, who still makes her smile, amidst dwindling memories. For my aunt, he is a friend, who stood by her side and taught her to find love in friendship. For me, he is the hero, targeted by despots who twist and turn all his words and actions, communicating with me through a medium, urging me to do the right thing.

References:

Ambwani, B. M. V. (2023, February 14). India’s Movie-Going Audience Pegged At 12.2 Cr, Down 16% From Pre-Pandemic Times. BusinessLine.

Bennett, E. (2021, October 28). The Kpop Comeback: Explained. The Lariat. https://srhslariat.com/12026/uncategorized/the-kpop-comeback-explained/

Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept. Gender and Society, 19(6), 829–859.

Dyahadroy, S. & Gole, S. (2023, July 30). Pathaan: Fractured Hope for Feminist Fans?. Doing Sociology. https://doingsociology.org/2023/07/30/pathaan-fractured-hope-for-feminist-fans-swati-dyahadroy-and-sneha-gole/

Kumar, P. (2023, July 30).Pathaan, Military Masculinity and the Possibility of a Queer Reading. Doing Sociology. https://doingsociology.org/2023/07/30/pathaan-military-masculinity-and-the-possibility-of-a-queer-reading-pushpesh-kumar/

Manil, B. M. (2023, July 30). Interrupted Histories: Pathaan, Ambivalent Fans and the Affection for Cinema. Doing Sociology. https://doingsociology.org/2023/07/30/interrupted-histories-pathaan-ambivalent-fans-and-the-affection-for-cinema-bindu-menon-manil/

NBC News. (2010, August 26). Celebrity Career Comeback Tips. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna38832058

Nagy, G. (2013). The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Harvard University Press. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Ancient_Greek_Hero_in_24_Hours

Waters, J. (2021, August 22). Constant Craving: How Digital Media Turned Us All Into Dopamine Addicts. The Guardian.

***

Ishani Ray is a Qualitative Market Researcher with a special interest in gender, media, and culture.

***

This essay is the latest addition to our Pathaan, Meri Jaan…Memoirs, Analyses and Reflections series curated by Gita Chadha. We thank Sayantan Datta and Sneha Gole for reviewing the essay and giving feedback.