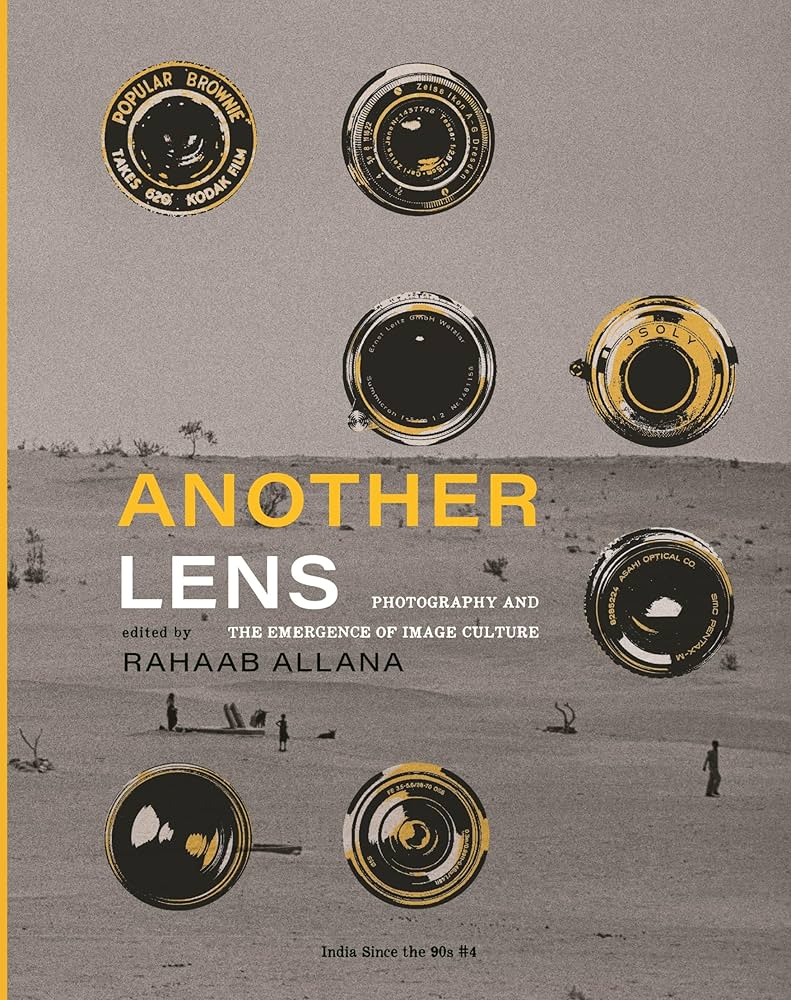

Another Lens: Photography and the Emergence of Image Culture edited by Rahaab Allana, (published by Tulika Books in 2024) compiles texts and images from a diverse range of scholars and practitioners to examine the historical, cultural and political dynamics of photography. This book, the fourth instalment in the six-volume series, ‘India since the 90s,’ illuminates the disruptions and gaps in visual culture spanning the 20th and early 21st centuries through the lens of the 1990s. Though not newly produced for this book; the novelty of the texts and images compiled here lie in the re-presentation, which, as the series editor Ashish Rajadhyaksha asserts, ‘evokes the ghosts of past histories.’

In a broader sense, the compilation critically analyses how the 1990s served as a pivotal intersection marked by economic liberalisation, globalisation, and the rise of digital technology, which collectively transformed the media landscape. The opening of global markets, the influx of foreign capital, and the onset of the telecommunication and digital revolution transformed image production, circulation, and their impact on society. This period also saw the emergence of new lens-based practices and a shift towards image hybridization which are highlighted in the chapters.

The volume is divided into four distinct sections which cumulatively bring out the dynamics of varying concerns such as history-making, ethicality, and questions of authenticity inter alia. Allana’s editorial vision is evident in its meticulous organisation, ensuring a seamless flow from one section to the next. The inter-woven texts singly or collectively highlight how the 1990s brought to purview innovative practices that deconstruct narratives leading to new sites of articulation, including subaltern realities (pg xi). It also brings to notice the expansion of the image spectra, printmaking, exhibition practices and viewership in relation to journalism, documentary, visual art, and shifting modes of media consumption among others.

The book commences with an introductory essay by the editor drawing a chronological arc through the landscape of visual media and cultural production. This is followed by the first section which deals with image-making practices of the late colonial and post-colonial era. It contains elaborate essays which explore issues like the Radcliffe Line, and how this critical historical moment not only depicts the partition horrors but also a history of map-making, barefoot cartographers, and individual artists. The section also explores how photography is used to document and interpret events, and how it negotiates the representation of reality. For instance, Sunil Janah’s photographs depicting crises such as the Bengal famine aimed to create and mobilize a mass public during India’s struggle for independence (p. 46). Additionally, the manipulation of photographs and images for propaganda and mass mobilization is discussed in Scott’s essay, which critically questions the objectivity of representing reality. The final two essays in this section focus on modern urban spaces and how they are popularized through professional and personal photography, serving as sites for creative interpretation and intervention (p. 81). In the concluding essay of this section, Gadihoke explores post-independence photography, reflecting on the representation of public space and questions if the subjectivities of the inner world could be appropriated and recast in the imagining of public space (outer world).

The second section broadly explores the emergence of experimental practices in photography by painters, media artists, photojournalists, and others. It examines how these new media practices challenge and rethink popular notions of the medium in modern India thus expanding the scope of photographic vision in Indian artistic practice. For instance, the essay by Throckmorton examines the relationship between local and global trends in image-making, highlighting how artists use new digital tools to deconstruct notions of ‘authenticity’ and propose narratives that challenge dominant historical perspectives and stereotypes (p. 136). The following essays in this section also explore various issues related to creating history, such as questions of authenticity and fidelity to sources. They also discuss different artistic experiments that the artists have implemented (for instance developing new forms of documentary as social critique, utilizing photography through a cross-pollination of perspectives, genres, and techniques) that challenge and expand the boundaries of the medium and its ability to represent reality accurately under the unbending scrutiny of the state as well as conservative/vigilante censorship.

The third section explores how the relationship between the photographer and their subject is regulated through an insider/outsider perspective. It deals with the ideas of documenting and re-visiting the past through technologically driven modes. The section in a way illustrates how new experiments in lens-based practices, enabled by digital capabilities, offer renewed psychological, psychic and narrative opportunities. The volume concludes with the fourth and last section comprising texts that bring in the issue of knowledge production and dissemination with regard to the notions of centre-periphery in the post-colonial art landscape. It also diffracts complex micro-histories of the invisible, suppressed and disenfranchised subjects through the lens of ethnicity, sexuality and identity.

In a nutshell, the book brings together texts and images that narrate a new story about the redefinition of photography in the 1990s. The texts broadly examine how art engages with issues of difference, power, and marginalization, and underscores the importance of de-historicizing and re-historicizing tensions in art. It also tackles the challenges of understanding art today, especially in a post-truth world filled with fake news and misinformation. Further, it also goes on to decipher the challenges practitioners grapple with including political issues, market transformations and shifts in photographic production. To its readers, this book promotes an ethical and careful way of looking at art, encouraging us to break down and rethink the stories and obvious messages behind images, while also focusing on decolonizing these narratives and overt representations. The collection calls for a thoughtful and open-ended engagement with art, encouraging the political and creative mobilization of diverse perspectives.

However, the book’s academic rigour might prove somewhat challenging for casual readers. The essays, though insightful and thought-provoking, often demand working knowledge of the concepts and ideas in visual culture. Nevertheless, for those prepared to engage deeply, “Another Lens” offers a rewarding experience. The diverse contributions from scholars and practitioners provide a brilliant amalgamation of lens-based practices to the creation of a modern image culture, making it an essential reading material for scholars, practitioners, photography enthusiasts as well as students of media and visual studies.

***

Moureen Kalita teaches Sociology at Krishna Kanta Handiqui State Open University (KKHSOU), Guwahati. She has a PhD in Sociology from the Centre for the Study of Social Systems (CSSS), Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi.