Textbooks have traditionally been the cornerstone of formal education in India, shaping the way knowledge is imparted and absorbed in classrooms. As noted in one of the newsarticles (Singh, 2024, June 25), the heavy load of school bags reflects the over-reliance on textbooks, with these resources becoming synonymous with the curriculum itself. According to the National Curriculum Framework (NCF) 2023, this heavy dependence on textbooks often overshadows the importance of other educational materials and resources. Beyond delivering structured knowledge, textbooks also embed societal values, biases, and ideologies, which subtly shape students’ perceptions of the world around them. One of the critical areas where these biases emerge is in the reinforcement of traditional gender roles.

India, in particular, has been identified as one of the worst regions in the English-speaking world for perpetuating stereotypes through the representation of women and girls in school textbooks, as highlighted by Crawfurd et al. (2024). This issue is not new; Krishna Kumar (1988) drew similar comparisons between Indian and Canadian textbooks, showing that Indian textbooks overwhelmingly feature adult or child males as central agents, while Canadian textbooks also favour male children in prominent roles. As Michael Apple (1980) asserts, school curricula represent ideological and cultural resources that originate from specific societal contexts, shaping the worldview of students. Stories, in both textbooks and real-life socialization, play a crucial role in shaping children’s perspectives. By engaging with narratives, children symbolically participate in the roles and viewpoints presented. Kumar’s (1988) study of Indian textbooks demonstrated that these narratives predominantly centre around male characters, reinforcing male dominance.

Krishna Kumar (1988) elaborates on the socialization impact of these educational materials in The Social Character of Learning, emphasizing that children’s understanding of societal roles is shaped by what they encounter in textbooks. If women are continually depicted as passive and subservient, students internalize the idea that girls are inherently less capable or valuable than boys. In his later work, what is Worth Teaching (1992), Kumar advocates for curricula that promote equality and critical thinking—qualities often absent from gender-biased educational content. This could also be seen in the analyses by Zaina (2022).

Indian textbooks further illustrate these biases. For instance, in the ICSE curriculum’s Hindi story “Bade Ghar ki Beti,” the absence of sons is lamented, portraying daughters as a source of disappointment. Similarly, Rajasthan’s English Rapid Reader includes a passage where a clerk expresses misery over having three daughters and no son. These narratives embed the notion that sons are assets, while daughters are liabilities, subtly reinforcing sexist views in educational material. (Zaina, 2022)

Kumar argues that textbooks are not just academic tools but also conveyors of cultural norms and societal expectations. When educational content perpetuates sexist narratives, it strengthens existing patriarchal structures, making them less likely to be questioned by young minds. Crawfurd et al. (2024) go further, linking gender-biased educational content to broader societal issues like female feticide, dowry harassment, and domestic abuse. These biased narratives, ingrained from childhood, shape perceptions of gender roles and responsibilities, which later manifest in harmful social practices. This analysis lays the groundwork for exploring how English literature in the CBSE Grade 1-3 curriculum perpetuates these stereotypes. Through content analysis, we can better understand how textbooks influence the socialization of students, reinforcing or challenging gender biases that persist in society.

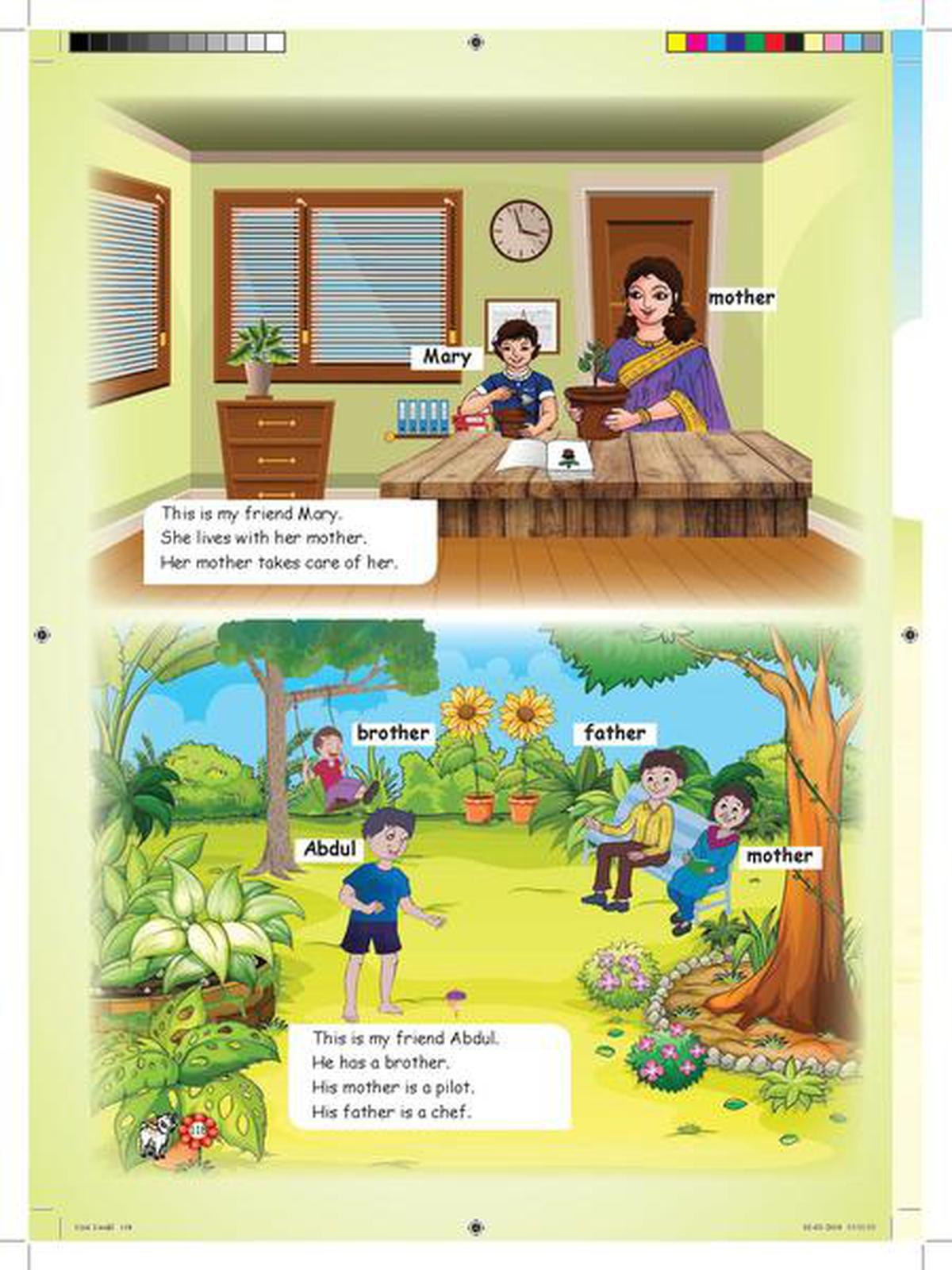

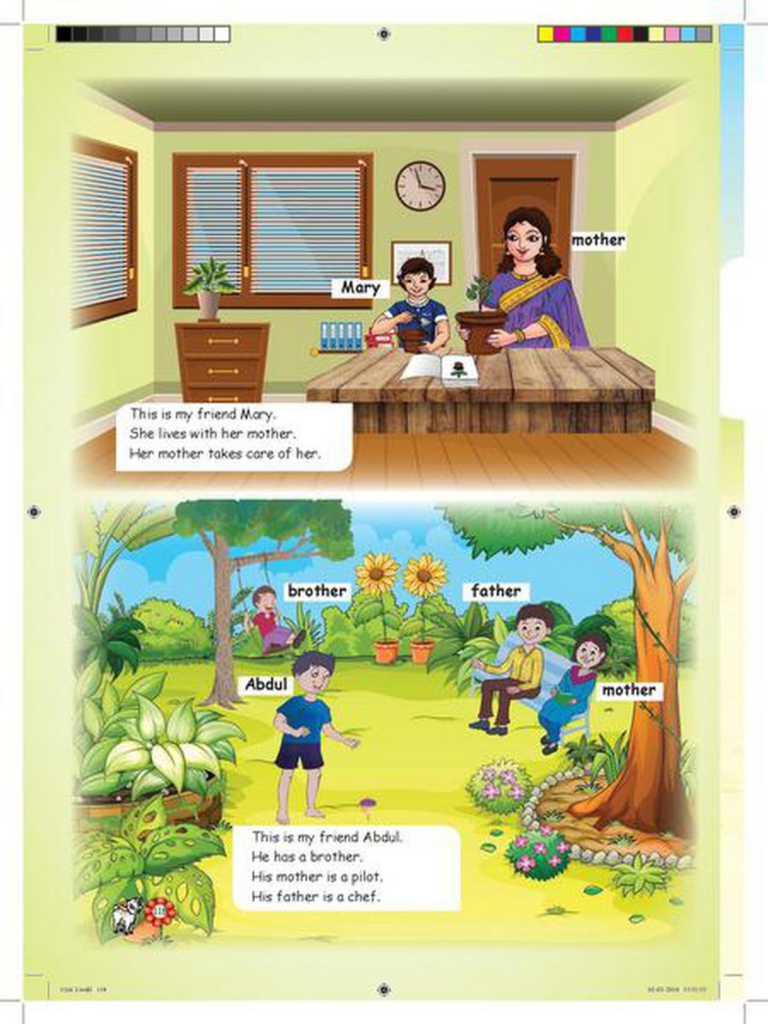

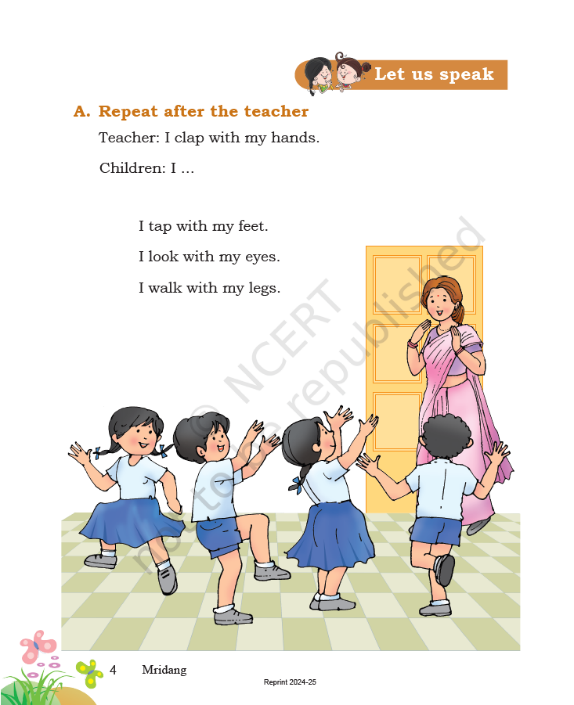

In the Class 1 textbook, Mridang[1], (p. 4), there is an image of a female teacher which perpetuates the stereotype that teaching is predominantly a female profession, subtly reinforcing the idea that certain roles are inherently suited for women. (Figure 1). Throughout the book, various exercises are designed for students to complete with the assistance of their teacher, often depicting women in these supportive, nurturing roles. On another page (p. 16), an exercise titled “Match the picture with the sentences” presents an option where a student sees their teacher, and the accompanying image once again shows a female teacher. These repeated representations contribute to the ongoing narrative that assigns specific gender roles, limiting the broader aspirations of students from a very young age.

In a similar vein, the Mridang textbook (p. 34), women are depicted taking care of their children outside the home, reinforcing the idea that their role is limited to caregiving. On another page (p. 87), the “Let Us Do” section includes an exercise titled “Bring one fruit to the class. Wash it well. Your teacher will cut the fruits. Your teacher will help you prepare a fruit chaat. Sit in a circle and enjoy eating it together.” Below this, there is an image of students sitting with the teacher, who is once again a female teacher. Nowhere in the textbook is a male teacher presented. The Class 3 textbook titled Santoor[2] (p. 3) features a section designed to teach students the alphabet with the letter Q. The text states, “Queue up quietly,” accompanied by an image on the left side depicting a female teacher instructing the students to follow this directive.

This illustrates how gender stereotypes are perpetuated in textbooks. Krishna Kumar emphasizes that the most significant lessons students learn are often not the explicit content but the underlying values embedded within the curriculum (Kumar, 1992). When textbooks do not challenge patriarchal norms, they contribute to the continuation of gender inequality. The National Curriculum Framework (NCF) acknowledges that rigid gender roles persist in society, highlighting the need for increased awareness among stakeholders that the ability to perform any job is not determined by gender. To address this issue, training modules for teachers, as well as resource persons and master instructors, must focus on this aspect. For instance, it is crucial to recognize that boys can pursue careers as nurses, and girls can take on roles as welders, as emphasized in the NCF 2023.

While the National Curriculum Framework (NCF) 2023 and educational institutions acknowledge the existence of gender stereotypes, these biases continue to persist, primarily through textbooks—an essential part of students’ learning experiences. The work that remains is to explore how these stereotypes are embedded in other textbooks and to identify effective strategies for dismantling them. A comprehensive analysis of textbooks across various subjects and grades is crucial to understanding the broader scope of this issue.

References:

Apple, M. W. (1980). Education and Power. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Bhalla, P. (2024). Textbook Culture: Pedagogy and Classroom Processes. Routledge.

Crawfurd, L., Mitchell, T., Nagesh, R., Saintis-Miller, C., & Todd, R. (2024). Lessons in Inequality: Gender Bias in Indian Textbooks and its Link to Societal Attitudes Towards Women. The Wire. https://thewire.in/education/lessons-in-inequality-gender-bias-in-indian-textbooks-and-its-link-to-societal-attitudes-towards-women

Kumar, K. (1989). Social Character of Learning. Sage.

Kumar, K. (1992). What is Worth Teaching? Orient Longman.

Singh, A. (2024, June 25). Kids with Heavy School Bags: Parents Urge Government Action. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bhopal/kids-with-heavy-school-bags-parents-urge-government-action/articleshow/111243397.cms

Zaina, N. (2022, August 1). Gender Bias in School Textbooks: Sexist Study Materials Prejudice Impressionable Minds. Feminism in India. https://feminisminindia.com/2022/08/01/gender-bias-in-school-textbooks-sexist-study-materials-prejudice-impressionable-minds/

[1] https://ncert.nic.in/textbook/pdf/aemr1dd.zip

[2] https://ncert.nic.in/textbook/pdf/cesa1dd.zip

***

Anjali Sidhwani is doing a MA in Sociology from the Department of Sociology, Delhi School of Economics (DSE), University of Delhi.