Introduction

The recent controversy at Laxmibai College, University of Delhi, over the use of cow dung as a cooling agent for classrooms has sparked significant debates in India. The principal of the college introduced this practice, claiming it as an environmentally sustainable method. However, the move quickly gained attention for its symbolic connections to Hindu nationalist ideologies, with critics accusing the administration of imposing a form of cultural nationalism. This essay explores the implications of the cow dung experiment within the broader context of politicisation, student welfare, and infrastructural neglect in Indian universities. The controversy not only highlights ideological tensions within academic spaces but also points to the material realities of neglecting basic infrastructure in favour of symbolic cultural practices.

Cultural Symbolism and Its Role in University Spaces

In Hindu tradition, cow dung is revered for its purity and sacredness, and its use in daily life, particularly in rural India, has been common for generations. Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of symbolic capital (1989) helps explain why such acts gain legitimacy in the eyes of certain groups: it is not about scientific evidence, but about cultural and historical resonance. The practice becomes normalized, affecting how public spaces are understood and experienced by students, staff, and the broader community. However, when this practice is introduced into modern educational institutions, it raises questions about the role of traditional practices in a space that should be driven by scientific inquiry. Antonio Gramsci’s theory of hegemony (1971) helps explain the symbolic function of such practices. According to Gramsci, dominant cultural values are propagated through consensual means rather than coercive force.

Michel Foucault’s concept of biopower (1976) also features the politics of such symbolic actions, referring to how institutions regulate bodies and behaviours. In this case, the introduction of cow dung imposes a cultural and bodily practice upon students, subtly aligning them with a particular vision of national identity and cultural purity. The university becomes a site not only for intellectual regulation but also for the shaping of cultural norms, attempting to position traditional practices as equally valid or superior to modern scientific approaches.

Saffronisation and the Political Agenda in Higher Education

The cow dung incident is not isolated but part of a wider trend of saffronisation in Indian educational institutions, where cultural and political ideologies are increasingly influencing curriculum, policies, and student life. Saffronisation, a term widely used to describe the rise of Hindu nationalist ideologies in educational spaces, represents a shift from secular to religiously motivated education. This ideological shift is not limited to changes in academic curricula but extends to everyday practices in universities.

Gramsci’s notion of hegemony is again relevant here, as the cow dung experiment can be seen as a means of normalizing Hindu nationalist values within the university. As Partha Chatterjee (2004) argues, the state plays a critical role in shaping what constitutes “appropriate” knowledge, and this often leads to the marginalization of alternative, secular, or scientific perspectives. It exemplifies the ongoing efforts to redefine educational institutions as sites for the promotion of a singular, ideologically driven national identity, further challenging the inclusive, secular traditions that have historically defined academic spaces. Nussbaum (2007) discusses how the rise of religious violence and cultural nationalism in India undermines democratic values, and the cow dung controversy fits within this broader trend. The push to institutionalize Hindu cultural practices in universities reflects a shift in political priorities, from fostering intellectual pluralism to promoting a singular, culturally defined identity.

Infrastructure Neglect and the Growing Student Discontent

While the cultural debate over the use of cow dung is significant, it also diverts attention from the material issues that Indian universities face, particularly poor infrastructure. The 2023 incident at Hansraj College, where a ceiling fan fell on a student during an exam, highlights the dangerous lack of attention to student safety and basic infrastructure. These incidents underscore a broader issue in Indian higher education: the prioritization of symbolic cultural practices over the real, pressing needs of students.

Ulrich Beck’s theorization of the risk society (1992) accounts for understanding how societies increasingly prioritize symbolic and cultural issues while neglecting the material risks faced by individuals. In this case, the use of cow dung as a cooling method, while presented as a sustainable solution, distracts from the lack of proper infrastructure and is a more immediate concern for students. The focus on cultural experiments in universities is a symbolic gesture that does little to address the day-to-day realities of students who face unsafe classrooms, inadequate facilities, and poor maintenance.

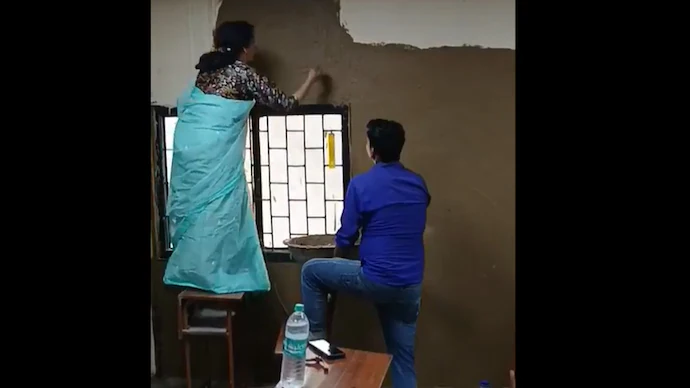

The critique from student leaders like Ronak Khatri, President of the Delhi University Students’ Union (DUSU), further emphasizes this discontent. Khatri’s protest against the cow dung initiative, which involved smearing cow dung on the walls of the principal’s office, was a clear critique of the administration’s priorities (Times of India, 2025). Khatri argued that students were more concerned about their safety and the quality of their education than about cultural experiments. His protest highlighted the growing frustration among students with the administration’s failure to prioritize infrastructural improvement over ideological agendas.

Student Activism and the Performance of Resistance

Student protests, such as the one led by Khatri, are key forms of resistance in the context of Indian higher education. Judith Butler’s concept of performativity (1990) can help us understand how student protests challenge the cultural and political impositions placed on them. In this case, Khatri’s act of smearing cow dung on the walls was a performative act that sought to disrupt the university’s cultural agenda and highlight the student’s dissatisfaction with the administration. It was an attempt to reclaim the space of the university as one where diverse perspectives and practical needs are prioritized over ideological impositions.

Khatri’s protest exemplifies the role of students as active agents in reshaping the political and cultural landscape of universities. As Judith Butler (1990) suggests, protests do not just express dissent but also perform the act of resistance, challenging the dominant cultural norms that are being imposed. Student-led protests, especially those that critique cultural nationalism in educational institutions, are becoming increasingly important as sites of resistance against the growing influence of political ideologies in academic spaces.

Conclusion

The cow dung controversy at Laxmibai College at the University of Delhi shows the growing intersection of politics, culture, and infrastructure in Indian universities. While the use of cow dung as a cooling agent has been framed as a sustainable and traditional solution, it also serves as a symbol of the larger forces of saffronisation and cultural nationalism shaping educational spaces. Universities are becoming sites where cultural and political ideologies are contested. At the same time, the protests led by students remind us of the importance of student activism in challenging these ideological impositions and demanding attention to the material needs of students.

References

Beck, U. (1992). Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. Sage Publications.

Bourdieu, P. (1989). The Logic of Practice. Stanford University Press.

Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of identity. Routledge.

Chatterjee, P. (2004). The Politics of the Governed: Reflections on Popular Politics in Most of the World. Columbia University Press.

Foucault, M. (1976). The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction. Pantheon Books.

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks. International Publishers.

Nussbaum, M. (2007). The Clash Within: Democracy, Religious Violence, and India’s Future. Harvard University Press.

The Times of India. (2025). DUSU President Smears Cow Dung on Principal’s Office Wall. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/du-students-smear-cow-dung-on-walls-of-principals-office-as-part-of-protest/articleshow/120330032.cms

The Economic Times. (2025). Delhi College Principal Smears ‘Gobbar’ on Classroom Walls to Beat the Heat, Students Say, “Asked for Fans, Not Cow Dung”. https://m.economictimes.com/news/new-updates/delhi-college-principal-smears-gobbar-on-classroom-walls-to-beat-the-heat-students-say-asked-for-fans-not-cow-dung/articleshow/120271854.cms

***

Simran Singh is a Master’s student of Sociology at Delhi School of Economics (DSE), University of Delhi, with academic interests in education, culture, law, and symbolic politics. Their research engages with the intersections of ideology, infrastructure, and everyday institutional life.

Awesome https://lc.cx/xjXBQT

Awesome https://lc.cx/xjXBQT

Good https://lc.cx/xjXBQT

Very good https://t.ly/tndaA

Awesome https://t.ly/tndaA

Good https://t.ly/tndaA

Good https://t.ly/tndaA

Good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Good https://is.gd/N1ikS2