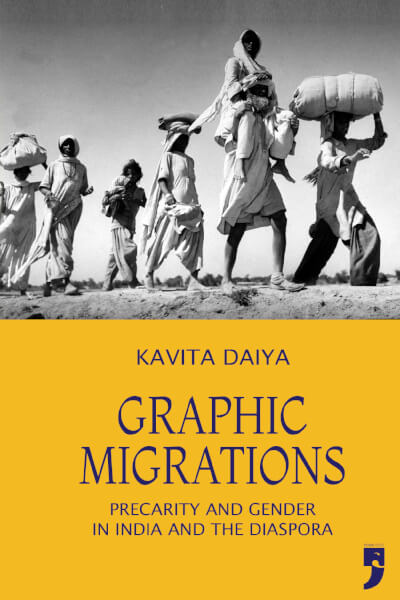

Graphic Migrations written by Kavita Daiya and published by Yoda Press, examines the 1947 Partition through the frame of the transnational, subaltern secular in the public culture. Affirming secular with heterogeneous cultural objects, it underscores Partition through the perspective of migrant, refugee and minority citizens, thus allowing for newer ways of imagining the community. It recognizes migrant/refugee/minority citizens as agents of national history contrary to dominant discourses which identify them as objects of pity, ‘outsiders’ or burden on the place. It maps how they are the political critics and the literal and figurative producers of secular imagined communities in postcolonial South Asia. The subaltern secular here is pitched against the ethno-nationalist rhetoric, which continues to exclude and create violence, thus undermining the very notion of the secular.

The book offers an exploration and analysis of the counter-public sphere constituting artistic, literary, and activist voices that perform and therefore affirm an alternative secular, tracing the expulsions of minorities and the intersections of caste, gender, religion, sexuality in these expulsions. The secular here is an ‘emergent secular’ – a resistant and embodied performance, an ethical mode of living identified in the space of public culture and everyday life and is constantly made and remade. Addressing the relationship between violent migration and this emergent/ mobile secular Daiyaexplicates the shaping of individual subjectivity and the collective community. Graphic Migrations focusses on transnational memory work based on archives – texts and objects. It thus narrates the Indian nation from the purview of migration, secularism, and citizenship, where some of these texts and objects have also been created by, or in collaboration with, Pakistani and Bangladeshi artists, cultural workers, scholars, and critics, making visible the intimacies of what otherwise gets understood as unconnected histories.

Chapter 1 ‘Partition Is Still Happening’: Transmedia and Graphic Secularism, places multiple images and graphics narratives on Partition in conversation with each other. It begins by discussing the hegemonic graphic representations like the ones in the Amar Chitra Katha and educational prints/charts which underscore a static, heteronormative inclusivity, reproducing hierarchies and erasing and invisibilizing the minorities; and then maps the visual economy of citizenship and statelessness through popular and subaltern images of migration and secularism in the vernacular print culture. The latter offers a critique of the postcolonial state reinstating memory work that foregrounds desires, histories, intimacies, and affects tied to border crossings foregrounding the experiences of the survivors of violence. It also challenges the understanding of Partition as an event of the past. It traces its ongoing violence for people who are still fighting to belong, have citizenship, and have access to a safe, dignified life.

Chapter 2, The Ethics and Aesthetics of Witnessing, focuses on literary representations that show how ethnic, political and economic violence is constitutive of the postcolonial nation-state, and at the same time, offer fractured narratives about the Partition. The author discusses two novels Cracking India and What the Body Remembers, both having female protagonists. On the one hand, they connect different forms of minoritizations enmeshed in the everyday, and on the other hand, bear witness to different forms of exclusions and political divisions. They thus, invent a subaltern secular through the production of empathy, solidarity and survival eschewing ethnic hatred.

Chapter 3, Melodrama, Community, and Diasporas in Popular Hindi and Accented Cinema, focusses on Indian art cinema and contemporary Bollywood cinema depicting minor subjects (gendered migrant/refugee/citizen) negotiating lived experiences of secular with religious nationalism. Here ‘melodrama’ of the Bollywood movies brings forth the crisis of secularism which fails to accommodate the humanist vision of community. These representations help make sense of securitization, policing, categorization and identity formation not just at the borders but within the nation-states as well; and also offer a critique of divisions and ethno-nationalism propelled by global media and geopolitics, reifying an affective and alternative secularism through humanity, intimacy and empathy.

The last chapter Transnational Asia, Testimony and New Media illustrates migration stories that destabilize the dominant nationalist histories to create new practices of the subaltern secular. Considering different texts and objects, from new media advertising to digital humanities archives, digital photo-based art installations, and oral histories, the author looks at the way technology and new media forms are being used to map what the author refers to as a just memory of Partition, allowing for ethno-political solidarities and transnational dialogue for peace.

The book brings alive an alternative perspective on the 1947 Partition through literary and media archives foregrounding the minorities and thus affirming a subaltern secular. It is also successful in not restricting the 1947 Partition to just an event that is static and fixed in time but traces its afterlife, which continues to make and remake people’s lives across transnational borders. Where on the one hand, it attempts to address the crisis of secularism and its gendered and ethnic production of statelessness, it also mentions (in the passing) the ever-growing crisis of secularism on the ground, which is becoming more and more dangerous for the minorities each passing day making the reader rethink the power and potential of alternative secular(s). The book is going to be a useful read for students and academics interested in 1947 Partition – in the field of literary studies, media studies, sociology and political science.

***

Aatina Nasir Malik teaches in the Department of Sociology, Indraprastha College for Women (IPCW), University of Delhi, New Delhi. She has a PhD in Sociology from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Delhi.