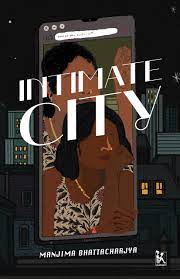

Manjima Bhattacharya’s Intimate City (published by Zubaan Books in 2021) traces the reconfiguration of sex work localities – ‘red light areas’ – with the advent of technology, digital apps and widespread gentrification. Tracing the changes in Kamathipura, one of the more acclaimed red-light areas in Mumbai (Bombay), the author examines the newer flows of sexual consumption, transactions as well as the changing nature of the city

Going beyond the HIV/AIDS research trajectory, as well as the more well-known feminist debates between abolitionists and rights activists, the book examines what globalization, digitization, and gentrification have done to an occupation that straddles precarity and stigma and lends itself to caste-based labour. While section one begins by examining the well-known history of colonial encounters with courtesans and the latter’s marginalization in independent India, it also looks at how changing cityscape and widespread use of the internet have rearranged the dynamics of commercial sexual transactions.

Section two begins with a brief history of Bombay (Mumbai) and its engagement with sexual commerce and changing forms of sexual labour. In understanding the changing spatial politics, this section examines how the slow dispersal of what counted as the ‘red light’ area was precipitated by a shift to the digital, which ensured a contraction of the physical space that constituted the moment of ‘encounter’ between the seller and the buyer. The section traces the experiences of sexual encounters, whether through caste-based performances or the introduction of mobile phones and access to the internet.

Section three and four plunge straight to the heart of the research – the organization of sexual transactions through the medium of digital spaces. What does the projection of desire in digital spaces tell us about our desires that work through aspirational caste and class markers? Reading through websites that offer escort services, the author examines how a sexual experience that borrows heavily on symbols of commodifed culture and the circulation of symbolic capital gives social legitimacy to the buyer. It is not just sexual gratification but the whole gamut of sexual-affective experience that is up for sale. Women are constructed as ideal companionate who offer curated behaviour that suits clientele taste.

One of the book’s key contributions is in understanding the consent of sex workers through the lens of the buyer. This is a crucial arena of investigation, as it cleaves through the complexity of the debate between sex as work and prostitution as exploitation. For buyers, women’s consent to the sexual transaction was an important factor that enhanced the experience of the fantasy world that they were momentarily transported to. However, what fascinated me most, was that the shift to the digital space also implied that women who offered sexual service were from ‘better’ backgrounds, making buyers eager to access their sexual and affective labour. The geographical space constituted the seller and her caste – the imagination was that the streets were for plebeian low-caste women, whereas those whose commercial transactions were mediated by the internet came from upper-caste communities; this imagination probably drawing its strength from digital literacy of the women.

Section four examines the liminality of online and offline sexual transactions, the lure of ‘independent operators’ vs’ agencies’, the various categories of clientele and the modality of class and caste aspirations, consent, danger, and surveillance. A section here deals with male ‘cruisers’ who perceive themselves as lovers rather than professional service providers, as men who satisfied women’s needs that went beyond what was available to them within the hetero-normative reproductive economy. The city’s loneliness, women’s sexual-affective dissatisfaction, the urge to live and love all merge in this section which elucidates women’s desires through the eyes of men who offer them momentary respite from a life wrapped around unacknowledged domestic and/or workplace drudgery.

The art of cruising (one of the titles of a sub-section) – a term that conventionally describes the practice of fleeting sex between men, anonymously and fugitively – probably does not do justice to the sub-section. The author opens to her readers a subterranean world that meshes desire with an ache for sexual-affective recognition, which goes beyond the transaction’s commercial nature. In my opinion, this section offers the freshest insights into how the city shapes intimacies— bought or offered.

The lacunae of the book lie in the fact that it is unable to draw on women’s narratives, a limitation that the author admits to, as she writes that they were wary of speaking to a ‘researcher’. The few narratives of women recorded in the book bring back the violence and insecurity inbuilt into such a precarious occupation. Not unlike those who seek employment in the urban informal sector, sex workers also struggle with debt, violence, exploitation, isolation, and lack of collective bargaining. The book significantly contributes to understanding the changing contours of sex work, desire, and its reconfiguration with the advent of digital spaces within a framework of caste, class and gender inequalities.

***

Panchali Ray is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Gender Studies, Division of Humanities and Social Sciences, Krea University.