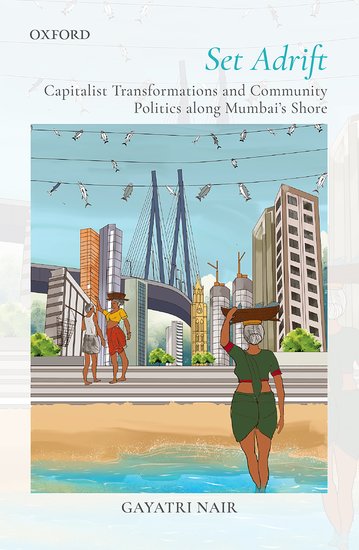

The book Set Adrift: Capitalist Transformations and Community Politics along Mumbai’s Shore (published by Oxford University Press) by Gayatri Nair, delineates the changing historical context of fishing as a livelihood for the Koli community and maps the changes in the occupation due to changes in the larger socio-economic and political terrain.

Divided into six chapters (excluding the conclusion), the book weaves the narratives of different stakeholders such as the fishing community, migrant labour, trawl owners, political party representatives and the State, establishing subtle connections which have far-reaching implications on fishing in Mumbai. This mapping assumes significance in the context of the traditional Koli community distancing itself from fishing activity because these factors reduced their access to commons, i.e. Mumbai’s marine landscape.

These changes in the larger context, along with aggressive mechanized fishing and ‘Pink Revolution’, resulted in a sharp dip in the fish’s regenerative capacity, impacting the livelihood security of the Koli community. Mechanization made fishing capital intensive. While it increased the production in fisheries that began predominantly catering to the export market, it alienated the community who were traditionally engaged in this activity. The Kolis were forced to fight to reclaim their fishing rights from the trawler owners and migrant labour who had entered the field.

In the author’s own words, “this book looks at the complex history that ties together large narratives of capitalism and the city, with smaller ones of a fisherwoman struggling to survive in fishing and a fisherman increasingly distancing himself from it.” The book unsettles the “popular imagination” of the “city” as “primarily linked to finance” and foregrounds the existence of livelihoods that draw from the commons in a city. For commons – in this instance, the seas – is not how commons are associated with the urban.

Through the journey in the book, Nair draws heavily from the personal anecdotes from her interactions with members of the Koli community and can draw insights into various institutional mechanisms such as the Fishing Cooperatives to mobilize the community to protect their rights over the commons.

Utilizing the framework of ‘accumulation by dispossession’, the book unravels that trajectory of fishing as an economic activity with export potential by creating labour reserves which not only attracted migrant workforce but also displaced the Koli community members who were then perforce compelled to seek wage labour outside fishing. The following observations from the book summarize this:

‘A focus on the process of accumulation by dispossession engenders not only an analysis on the specific outcome for the fisheries in Mumbai but also focuses attention on a macro analysis of the development of capitalism. The process of uneven development that has become characteristic of capitalism is critical to processes of accumulation’ (pp. 9-10).

The social exclusions and othering compound the story of economic dispossession that ethnic divisions in the labour force led to. The entry of migrants (perceived as outsiders) has resulted in the division of the workforce along ethnic lines, which has implicitly resulted in the political mobilization of the Kolis primarily against ‘outsiders’ of another marginalized community rather than a united struggle against those who wield power.

Drawing from observations from Edna Bonacich (1972) about the racial divide in the American labour force, Gayatri Nair identifies that the conflict in the fishing sector is centered on capitalism’s need for a cheap and docile workforce and class inequalities between these groups.

The book highlights how the larger economic forces have rendered this community powerless without providing them with any platform for articulating their demands and aspirations. In this context, federations such as Maharashtra Machimaar Masivikreta Sangh (MMMS) and National Fishworkers’ Forum (NFF) have come to the rescue of the Koli community protecting their fishing rights.

In conclusion, Nair argues that the split labour market theory is useful for understanding the current situation of fisheries in Mumbai, particularly to identify the reasons as to why the entry of migrant labour force into one sector has seeped as ethnic antagonism into the larger geographical landscape of Mumbai. Split labour market theory traces the roots of racial/ethnic stratification to social and political differences that predate inter-group contact in the labour market but argues that the specific outcomes (caste system, exclusion, or something else) result mainly from the actions of the higher paid segment of the working class and their power relative to that of capital.

Further capitalism driven urbanization threatens the work and living sites for the urban poor in general and the fishing community in particular. Along with urbanization, many ‘developmental’ projects displace or impact the livelihoods of the resource-poor in an irreversible way, which needs to be recognized and acknowledged. In this context, the vulnerable communities like the urban poor and the fisher community must build solidarity and generate this sense of community which could go a long way in tackling the diverse modes of capitalist exploitation.

***

Laxmi Vadapalli is a Senior Fellow at SaciWATERs, South Asia Consortium for Interdisciplinary Water Resources Studies, Secunderabad.