An anonymous quote from the internet says: “Don’t let your mind bully your Body”[i].

Herbert Mead’s Mind, Self and Society would argue that the mind, self and society are constituted conterminously. The bully, as sociology would teach us is thus both outside and inside one’s mind. Our take of the significant other defines our sense of selfhood. Our selves and minds emerge in interaction with others (Mead, 1934). Our knowledge of ourselves is mediated by the knowledge that others have of us.

Michel Foucault emphasises the constructedness of such knowledge in the creation of norms that are deemed desirable in society and the individual’s tendency to abide by them. Foucault develops the idea of biopower which can be divided into anatomo-politics of the body (disciplinary power) and biopolitical power of the body. Disciplinary power produces ‘docile bodies’ (through disciplinary sites such as schools, prisons, and hospitals) which can be ‘subjected, used, transformed and improved’ (Foucault 1977, p.136) while biopolitical power ‘administers life’ (Foucault 1978, p. 138) as it tries to ‘optimise’ the life of populations (Foucault 1978, p. 139).

Biopower includes scientific and medical experts; dissemination of scientific literature ranging from specialized science journals to popular magazines, websites, and blogs; techniques and equipment to monitor and measure certain physiological values.

My exposure to such sociological knowledge that emphasised the complex and subtle ways that our sense of our bodies is constituted occurred late, with my exposure to sociology. But my awareness of the body as an object occurred earlier. I seek to describe this process in this paper.

The Body as an Object

From my childhood, I have been a chubby kid. In the various sub-urban towns of Assam, where I spent my childhood, I was never exposed to the power of notions associated with appearance. The awareness dawned on me when I moved to Guwahati, where I encountered students from diverse backgrounds.

Apart from learning new urban vocabularies, I came into contact with the notion of objectification of the body. There are dominant ideas in society about the ideal female and male body. These ideas are produced and transmitted through the different social institutions such as the family, schools and in contemporary societies, mass media.

Schools are one of the key socializing agents that contribute the most to social conformity. Members of such institutions bring the ideas gathered outside the walls, to be shared and reproduced inside, including the objectification of the body and demarcation of ‘fit/good’ and ‘unfit/bad’. Along with academic competition in my school, the idea of a desirable body affected one deeply. The dominant cultural ideals of what constituted male attractiveness impinged upon oneself. People that did not fit in faced an acute sense of exclusion. Being a chubby kid put me in the periphery when it came to outdoor activities. I would be one of the last ones to be picked for a football or a cricket team. Acceptance into a new group of people was tough for someone like me, who was not only an outsider but also did not conform to the ‘ideal’ male body image.

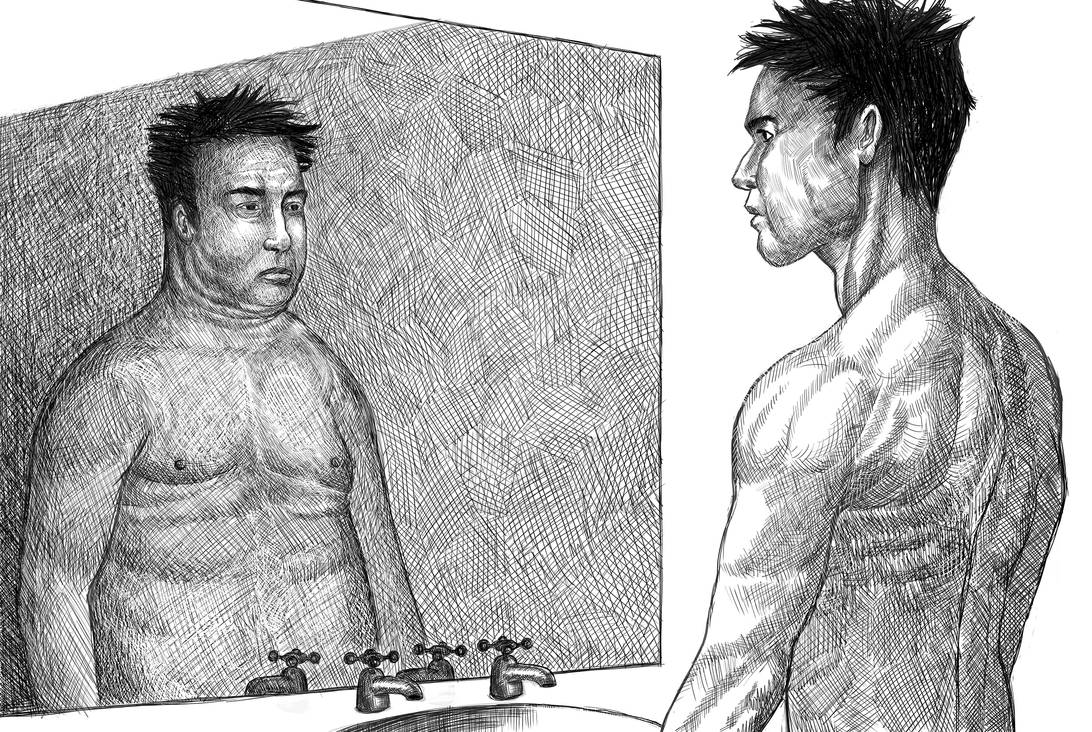

Male-breasts and the image of ‘Self’

Many men have to face the unwelcome development of male breasts. The reasons for this could range from hormones to life-style[ii]. This leads to chest dysphoria which is not just a transmasculine issue but also pertains to cisgender males. The distress and discomfort due to unwanted breast development are acutely felt. It is widely seen as a taboo associated with a sense of shame in conservative Indian society. It has been an issue that many adolescents and adults have to battle alone.

Physical appearances are one of the factors that foster stereotypes as they are one of the most obvious markers of gender traits (Deaux and Lewis, 1984). This leads to the victimization of those who do not fit in. It is an integral part of the bullying culture prevalent in many schools. Dan Olweus (1978) identifies bullying as an aggressive and repetitive behaviour of asserting power over one who cannot defend himself/herself. This power may also be achieved by knowing the victim’s vulnerabilities (Menesini and Salmivalli, 2017). In the case of ‘male breasts,’ the vulnerability lies in the physical appearance. Having a body that does not conform to the dominant image is seen as deviant. It provides an opportunity for the ‘perpetrators’ to assert their dominance by physical and mental harassment. This idea of shaming has been reiterated by thinkers such as Cooley (1922) and Mead (1923) who believed it to be a social process that is facilitated if and when one strays away from the expectations of others. This non-conformity paves way for shaming and consequent bullying. The interaction that took place between me and my peers moulded how one thought of oneself as a ‘man’. As Cooley (1922) suggested, others’ perceptions about us shape the way we see ourselves and as Mead (1934) suggests, the social process of interaction helps in developing a ‘self’.

According to the Objectification Theory (Fredrickson and Roberts, 1997), this self-objectification manifests itself in monitoring our outward appearance, which becomes more important than our thoughts, goals, cognitive credibility and physical well-being.

Consuming Media’s Narrative

There has been a sizeable amount of research on how such ideas of a perfect body are spread through traditional media, especially televisions (Barlett CP, Vowels CL and Saucier DA, 2008). Cinema and advertisements have had a massive impact in shaping such notions. From having a ‘zero figure’ for a female, to ‘six-pack abs’ for a male, the images drawn of an ‘ideal body’ are powerful and persuasive. These ideas are enhanced and fuelled through the mainstream Bollywood movies as well, where the ‘Hero’ would present himself with a physique that epitomized masculinity (with exceptions like Govinda). Social media has also facilitated such notions as it portrays an idealized version of oneself. This then becomes a reason for self-objectification for others.

Coping the Slurs

As adolescents tend to worry more about some parts of their body, they use a wide range of coping mechanisms when it comes to body image. Another study (Cash, Santos and Williams, 2005) developed a Body Image Coping Strategies Inventory that states people use remedial strategies such as avoiding threatening emotions or situations or the urge to fix the appearance deemed imperfect. Avoidance of exposing ‘male-breasts’ may include not participating in physical activities, hiding it by wearing loose t-shirts or an attempt to fix it with excessive diet control and exercise. According to Goffman (1963), individuals seek to gain an idealised version of themselves to combat the stigma associated with others’ perceptions. Probably that led me, like many others to adopt practices like sporting a beard, avoiding long hair when I entered college so that I do not face a backlash regarding sexual identity which I did during my school days in Guwahati. Along with physical training, I cut down severely on my diet, to a point that I shed around 20 kgs within 6 months. I was not healthy, but leaner, but it nonetheless changed the perception of ‘others’ which surprisingly instilled confidence in my personality as well. I started to accept the current version of myself regardless of the repercussions of the practices. This was in tune with what society deemed ‘normal’ as a man; less fat, rustic, rough.

The attempt to gain ‘normalcy’ also helps contribute to the health discourse. As Foucault (1975) would suggest, it helps the fitness and medicine industry gain further relevance in demarcating the ‘normal’ and the ‘deviant’. Either one adapts medical help, or that of the fitness industry to chisel oneself, or unhealthy dieting which could lead to medical issues down the line.

For a cissexual male, the desire to attain a ‘perfect body’ dominates one’s consciousness and sense of selfhood. A deviant body image raises existential questions of oneself and the virtues of masculinity. The idea that a toned, muscular body is attractive and sexually desirable (Frederick, Fessler and Haselton, 2005) particularly and more so without ‘male-breasts’ governs one’s life. It’s a struggle to achieve the ‘dominant’ socio-cultural image of being ‘masculine’. For adolescents from my era, who are grown adults now, the insecurity was fed by the pervasive presence of dominant images of a desirable male body. The question yet needs to be asked, do the ‘victims’ conform to the ‘bio power’ of cultural ideals, or does the world need more tolerance?

References:

- Barlett CP, Vowels CL and Saucier DA (2008). Meta-analyses of the effects of media images on men’s body-image concerns. J. Soc. Clin.Psychol, 27: 279-310.

- Bourdieu, P. (1977). Cultural reproduction and social reproduction. In J. Karabel& A. H. Halsey (Eds.), Power and ideology in education (pp. 487-511). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cash, T. F., Santos, M. T., & Williams, E. F. (2005). Coping with body-image threats and challenges: Validation of the Body Image Coping Strategies Inventory. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58(2): 190-199.

- Cooley, C. (1922). Human Nature and the Social Order. New York: Scribner’s.

- Deaux, K., and Lewis, L. L (1984). Structure of gender stereotypes: Interrelationships among components and gender label. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 46: 991–1004.

- Foucault, M (1975). The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception (A. M. Sheridan Smith, trans.). New York: Vintage Books.

- Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (A. Sheridan, Trans.). New York: Vintage Books.

- Foucault, M (1978). The History of Sexuality. Volume I: An Introduction. Robert Hurley, trans. New York: Vintage.

- Frederick, D. A., Fessler, D. T., &Haselton, M. G. (2005). Do representations of male muscularity differ in men’s and women’s magazines? Body Image, 2: 81–86.

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs.

- Mead, G.H (1934). Mind, Self, and Society. United States of America: The University of Chicago Press.

- Menesini E, Salmivalli C (2017). Bullying in schools: the state of knowledge and effective Interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine 22(1): 240-253.

- Olweus, D. (1978). Aggression in the schools: Bullies and whipping boys. New York, NY: Hemisphere Publishing.

[i]https://in.pinterest.com/pin/334744184806671058/

[ii]Fletcher, J (2019). Everything you need to know about man boobs. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/326637