Source: Scroll.in

Introduction

The nationalist struggle for India’s independence was not just a mere political one. Rather it was an iconoclastic project, the waves of which made significant inroads in transforming the cultural space of the nation. The nationalist ideology of colonial times separated the cultural domain into two spheres – the material and the spiritual. Predominantly dominated by men, the material sphere emerged as the external ground of Western acquisition. The bahir became the space where modern methods of statecraft, science, technology and rational forms of economic organization were integrated into the social fabric of the country. However, these modes of structuration were intrinsically attached to a European imagination of nation and nationhood, which led to a need for establishing a distinction between the West and the East (Chatterjee, 2010). This necessity to carve out a different identity, an identity that was not based on mere imitation of the West, gave rise to the narrative of a perceived superiority of the Indian spiritual sphere. Within this spiritual domain, the home, sanitized from the shadows of the coloniser, emerged as the symbol of India’s true identity. And since the andar is almost always associated with women, they became the natural ‘protectors’ of the nation’s spiritual realm (Chatterjee, 2010).

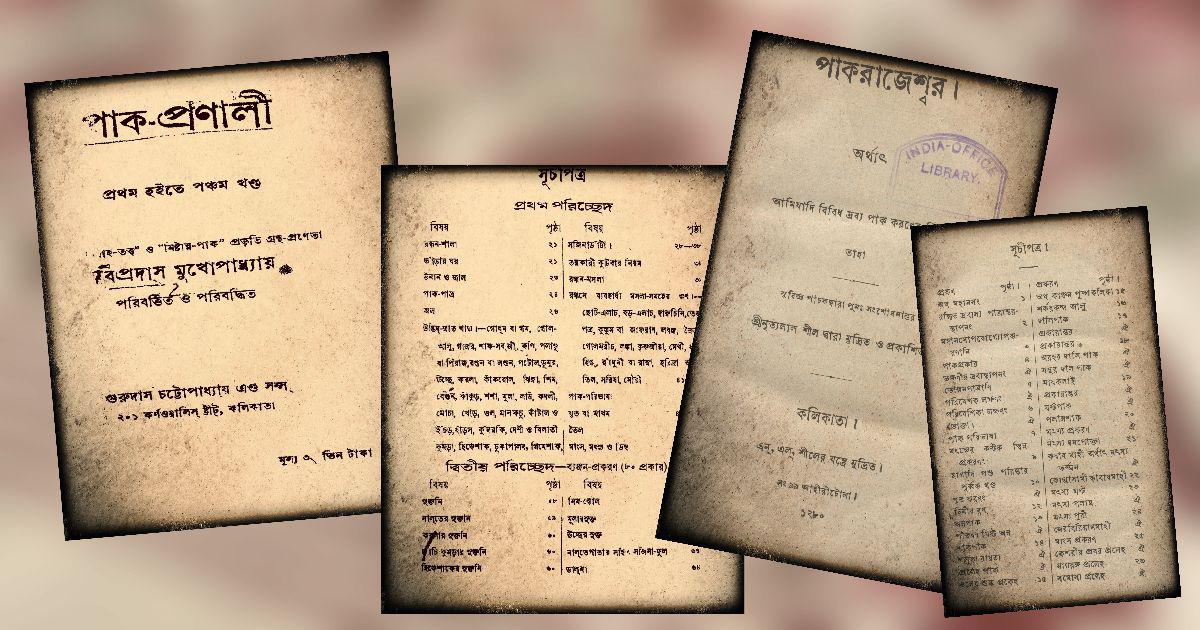

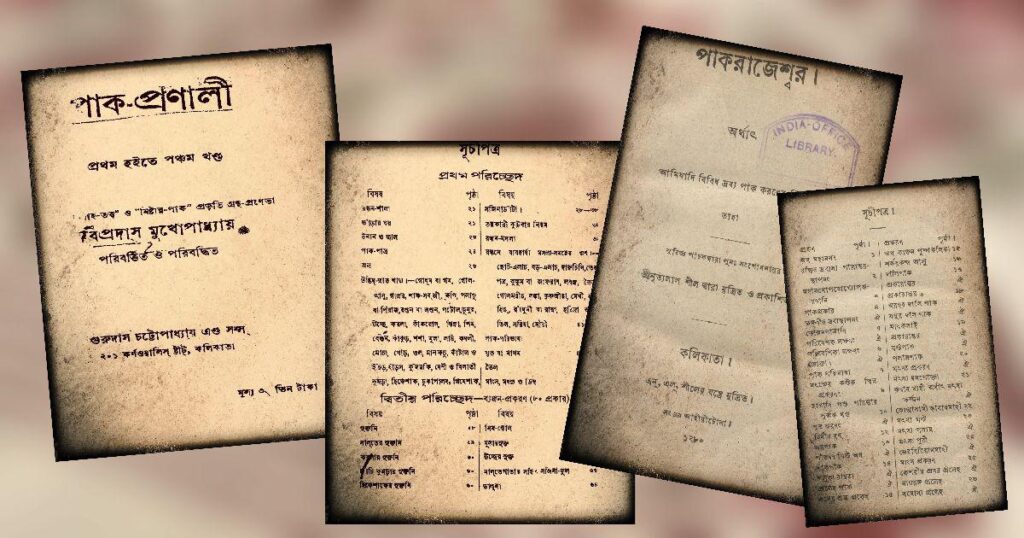

Inside the contours of domesticity; the hearth, the food cooked in the kitchen and the choice of nutrition appeared to be one of the foremost ways through which Indian tradition was upheld. Several popular discourses of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century were centred around the designing of culinary practises as expressions of deshachar, the rituals of the nation or the desh; through which the cultural project of nation-building was addressed (Prasad, 2006). Therefore, ‘food became the cultural and ideological register’ (Prasad, 2006, p. 256) for resisting European influence. Against such a backdrop, several members of the middle-class intelligentsia published culinary texts like cookbooks, household manuals, journals and periodicals to preserve India’s culinary heritage. By stressing the importance of gastronomical self-sufficiency which was away from the clutches of the Europeans, these texts played a very significant role in the nation-building project. They documented cultural tales ‘of shifts in the boundaries of edibility…the proprieties of culinary process… and the structure of domestic ideologies.’ In this manner, they not only remained as ‘representations of the structures of production and the distribution of social schemes but also of class and hierarchy’ (Appadurai, 1988, p. 3). The kitchen, as it appeared in the culinary texts, romanticized the idea of tradition and the notion of meals cooked by the women of the household which, according to the intelligentsia, would help in retaining their distinct Bengali identity (Ray, 2009).

Hence, as battles were being fought in the public domain, slowly and steadily, the interior makeup of the home and in turn, the nation was being transformed. The andar mahal, as depicted in the colonial culinary texts of twentieth-century Bengal, gradually emerged as a potent ground for the unfolding of the project of nation building; a project that was intrinsically entrenched in narratives of gender and class.

Custodians of National Honour

The concept of class is generally portrayed to be solely an economic category. However, in reality, it does not always get defined by economic considerations. The cultural aspects play an equally important role in defining the identity of a particular strata, which emerge as the symbolic markers of a social class. According to Bourdieu, an individual can belong to a specific class, only if he can legitimize his position through his cultural capital, which on getting sufficiently validated gets converted to symbolic capital. Therefore, belonging to a social class requires the presence of symbolic artefacts, which eventually become responsible for the politics of inclusion and exclusion (Lawler, 1999). In the context of colonial Bengal, an individual’s food habits and dining patterns emerged as important pathways to reveal the identity of their social class.

Food in the early twentieth century became the signifier of a refined middle class which distinguished them from the working class on one hand and the Europeans on the other. It articulated a discourse of taste and a culture of food through which women’s everyday labour in the kitchen space was obliterated. Hence, the culinary texts and the discourses of 20th-century Bengal engaged in a celebration of the labour of women as a labour of love to contribute to a project of nation-building as well as to promote a certain class distinction (Ray, 2009).

For example, Bipradas Mukhopadhayay’s Pak Pranali commented that a man can only find peace and satisfaction in the food cooked by his wife and not in the dishes prepared by a paid cook. Pragyasundari Devi’s Amish o Niramish Ahar lamented the fact that Bengali women no longer cooked for their families. Thus, the presence of servants in middle-class Bengali households became one of the biggest concerns for the authors of household manuals who accused the Indian women of having become lazy due to their interaction with Western notions (Choudhury, 2016). In this manner, the nabina or the new woman (the identity of whom was a result of colonial modernity) was often reprimanded for their reliance on professional assistance due to their inability to cook (Sengupta, 2010). So as the home emerged to be a ground for preserving the spiritual sanctity of the nation, the involvement of domestic helps in the kitchen and household spaces came to be seen as an encroachment of the inner domain. Further, since the domestic help generally belonged to a different class, caste and community from their modhyobitto (middle class)employers, eating food that was cooked by the perceived ‘other’ carried the possibility of ending the class distinction of the middle class (Choudhury, 2016). So the authors of the culinary texts reflected the bhodrolok’s anxiety about the loss of their identity.

As a result, middle-class women took upon the role of being completely involved in the domestic sphere, thus expanding their responsibilities as custodians of the home to the custodians of national honour and dignity. Against the backdrop of such spiritual reformation emerged the category of the ideal modern grihini or the mistress of the household. She was quite the reverse of the ‘common’ woman who was loud, vulgar and coarse. Instead, she was expected to acquire the cultural refinement provided by modern education without jeopardizing her role in the domestic spaces (Chatterjee, 2010). She was also required to be skilled in both the new as well as the old ways of cooking. Only then would she be classified as a bhodromohila, a woman who was not as Westernized as the English memsahibs, but not as unrefined as the lower-class Hindu women.

Health and the Nation

Besides attempting to construct the identity of the Bengali women, the colonial culinary texts provided a special emphasis on the category of health and healthy eating. ‘The heat and humidity were seen to be the factors which subverted manliness, resolve and courage’ of the Bengali middle class (Sengupta, 2010, p. 86). Further, the rice-laden diet of the Bengalis was believed to be a reason for the effeminate characteristics of the people of the East. At the same time, popular contemporary newspapers like The Hindu Patriot and the Amrita Bazar Patrika published articles on the rising cost of edibles, routinized famines and the increased adulteration of food. These precarious conditions with regard to the foodscape of India gave birth to a disease-stricken middle class which was severely hit by poverty (Prasad, 2006). As a result, the colonisers emerged to be the examples of a hyper-masculine social class, who were naturally perceived to rule over the weak and unhealthy Orient, due to their superiority in strength and economic prowess. Therefore, the authors of the colonial culinary texts were gravely worried by the ailing body of the middle class, which eventually became a metaphor for the ‘feminine’ nature of the Bengali bhadralok samaj and the whole of the colonised land of India.

Hence, the burden of the degeneration of Bengali health was attributed to the colonisers, who took away the masculine nature of the middle class. For example, Rajnarayan Basu, a Brahmo reformist intellectual, wrote in his essay Se kal ar e kal, ‘We have seen in our childhood numerous examples of how much people could eat in those days. They cannot do so now’ (cited in Sengupta, 2010, p. 88). Here, ‘those days’ become a reflection of the glorious Hindu past where food was available in plenty. Such a narrative was in complete opposition to ‘these days’, the lived reality of which was steeped in crises and deterioration. So, the 20th-century cookbook writers emphasised on the portrayal of India’s culinary knowledge by tracing it to the ancient days of the Epics and the Vedas. Bipradas Mukhopadhyay commented, ‘The analysis of ancient Indian history shows that like other educations, culinary education also flourished in India. The Aryans realized that people’s power, intelligence, and life-span – all were dependent on food. Therefore, they had shown much expertise in food selection and good arrangement of cooking’ (cited in Choudhury, 2016, p. 6).

Similarly, Rwitendranath Tagore, of the famous Tagore family, claimed that the terms for European food like pies and pancakes were derived from Vedic roots. For example, the Vedic ‘pup’ (cake) and pie belong to the same genre of food. Hence, he believed that ‘pup’ became distorted to ‘pie’ in English. Further, according to him ‘pastry’ was derived from the Sanskrit term pishtak (Ray, 2012). Therefore, by relating India’s history to the Aryan civilization, there was an inherent endeavour among the cookbook writers to glorify the ancient Hindu past. Such an attempt to carve out an alternate imagination of the nation was a definite extension of the nationalist project of Hindu revival, which was characteristic of the twentieth century’s struggle against colonialism. Hence, through the culinary texts, food and health emerged to be the key areas of Bengali life which represented the remembrance of a lost culture. This lost culture had to be restored by the reformation of the degenerated private domain of the home, kitchen and hearth, which would assist in portraying the Indians to be superior to the colonisers. Therefore, the nation-building project undertaken by the Bengali middle class of the colonial times was based upon the reconstruction of the bygone culture of glory and honour.

Concluding Comments

Benedict Anderson has shown that print capitalism is one of the many ways by which a group which has never actually met each other face to face could begin to think of themselves as Indian (Appadurai, 1996). Through the ‘conditions of collective reading, criticism and pleasure, a group begins to feel things together’ as a community (Appadurai, 1996, p. 8). This is how the twentieth-century culinary texts of Bengal managed to establish the middle class as a distinct social category through the practices of consuming and preparing food. Taking the help of Bourdieu’s argument on class, this paper has attempted to show that the interaction with food helps the bourgeois in forging a relationship with the social world. In this sense ‘taste operates as a weapon, creating class awareness about the things one chooses to consume’ (Das, 2021, p. 136). Therefore, even though the Bengali culinary texts attempted to limit the roles of the bhodromohila to those of the wife, the mother and the homemaker; they also assisted in carving out an imagination of the Indian nation to showcase the aesthetic superiority of the middle class when compared to the West. Hence, we can safely conclude that the narratives of gender and class constituted the project of nation-building, in the context of twentieth-century Bengal.

References:

Appadurai, A. (1988). How to Make a National Cuisine: Cookbooks in Contemporary India. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 30(1), 3- 24.

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. University of Minnesota.

Chatterjee, P. (2010). The Nationalist Resolution of the Women’s Question (1989). In Partha Chatterjee & Nivedita Menon (Eds.), Empire and the Nation: Selected Essays, (pp. 116 – 135). Columbia University Press.

Choudhury, I. (2016). A Palatable Journey through the Pages: Bengali Cookbooks and the “Ideal” Kitchen in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century. Global Food History, 1 – 19.

Das, R. (2021). The Labour of Love: Changes in Consumption Practices in Late-Twentieth Century Calcutta. In R. Harde and J. Wesselius (Eds.), Consumption and the Literary Cookbook (pp. 134 – 146). Routledge.

Lawler, S. (1999). ‘Getting Out and Getting Away’: Women’s Narratives of Class Mobility. Feminist Review, 63, 3 – 24.

Prasad, S. (2006). Crisis: Identity and Social Distinction: Cultural Politics of Food, Taste and Consumption in Late Colonial Bengal. Journal of Historical Sociology, 19 (3), 245 – 265.

Ray, U. (2009). Aestheticizing Labour: An Affective Discourse of Cooking in Colonial Bengal. South Asian History and Culture, 1(1), 60-70.

Ray, U. (2012). Eating ‘Modernity’: Changing Dietary Practices in Colonial Bengal. Modern Asian Studies, 46(3), 703 – 730.

Sengupta, J. (2010). Nation on a Platter: the Culture and Politics of Food and Cuisine in Colonial Bengal. Modern Asian Studies, 44 (1), 81 – 98.

***

Currently working in the developmental sector, Rageshree Bhattacharyya has recently completed her post-graduation in Sociology from the South Asian University (SAU), New Delhi. Her research interest includes the sociology of food, anthropology of work, gender studies and anthropology of waste.