Introduction

The word ‘classical’ is problematic today with the carving out of a convenient space that distorts history to its horrifying and improbable extent. Today, politics as well as society is undergoing the face of what late Marxist Scholar T.K Ramachandran calls the ‘ultra-conservative backlash’ (Ramachandran, 1995). He writes:

Nurtured diligently by the popular media, and aided and abetted by the establishment, the ‘backlash’ has become a well-entrenched and palpable ideological entity in our daily life. Further, its pernicious influence has eroded, to a great extent, the unquestioned hegemony that the progressive forces had enjoyed in cultural life. Certainly the ‘backlash’ is a nebulous phenomenon, eclectic in its ideological composition and protean in its manifestations. This is perhaps no accident when we consider the curious chemistry of ruling-class alliances in response to which the backlash ideologues modulate their voices (Ramachandran 1995).

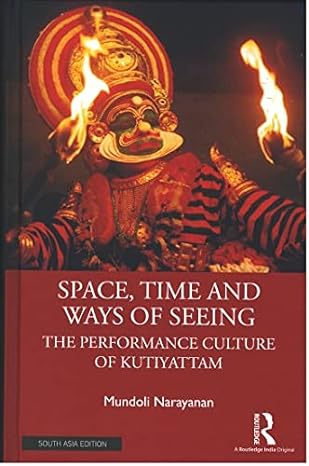

Living in such a time when the author of the book Space, Time and Ways of Seeing: The Performance Culture of Kutiyattam, Mundoli Narayanan is ousted from his Vice Chancellor position, this book review tries to re-capture and drive home the point that today we live in a world of the ‘ultra-conservative backlash’. Academic expertise is no longer academic expertise and works of international repute that have garnered global critique are least important in academics. Such a kind of academic space is what is supplanted today, and this is particularly evident in humanities and social sciences.

Having said that, one can in a way discern that backlashes carry with them an ultra-conservative nature where mistakes will no longer be treated as mistakes, ‘false’ one day might become the biggest truth the next day (perhaps such a transition can happen even in seconds). Hence if one decides to move on without paying much heed to the nitty-gritties of mistakes or falsities, it might soon turn out to be a norm that is here to exist. Needless to mention not only are they conservative but also systematic in twisting histories. Kutiyattam the classical art form comes as an open door for such historical twists in such a backdrop. But Narayanan secularizes such an art form and places the past of Kutiyattam diligently with the present. Such a radical act also puts the book as an open-ended document that carries the culture of Kutiyattam to an eternal stage.

Ways of seeing the text

Through speaking history as it is, not just in chronological terms, but also from the changing performative space-time challenges in terms of digressions, Narayanan positions the classical aspect of Kutiyattam to its perfection with this critical text. An interesting aspect of seeing Kutiyattam through the lens of the ‘other’, in the changing modernist discourses makes this book even more interesting. Living in a right-wing setup that largely attempts to take anything of historical importance into account, this book comes as a critical text that has brushed ‘history against the grain’. The author has transcended such a serious issue of right-wing manifestation and its impact on art forms quite warningly, as is required, but also eloquently through carving out a space for Kutiyattam, by positioning the art form as an art form for all, at the same time a political play both in terms of seeing as well as in terms of its performance. Such a democratizing of the art form makes this text worthy to be considered one of the best-documented studies ever conducted in the field of Kutiyattam too.

Walter Benjamin in his Theses on the Philosophy of History warns us that:

Historicism content itself with establishing a causal nexus of various moments of history. But no state of affairs is, as a cause, already a historical one. It becomes this, posthumously, through eventualities which may be separated from it by millennia. The historian who starts from this ceases to permit the consequences of eventualities to run through the fingers like the beads of a rosary. He records [erfasst] the constellation in which his epoch comes into contact with that of an earlier one. He thereby establishes a concept of the present as that of the here and now, in which splinters of messianic time are shot through (Benjamin, 1992).

Narayanan identifies the importance of historicism quite acutely in such a backdrop where he identifies the processes of the mind, body and spirit with precision. Such precision is achieved because of the intense politicizing of the art form to the best of its potentialities, at the same time most importantly without any dilution with history.

The processes of the mind and the processes of the spirit are largely implicated in one’s body and an implication of such a kind most of the time comes as a poetic representation in many of the classical literatures. These classical literatures in a way bring with them an idea of a renewed modernity that cannot fail to grasp hold of the here and now. Such a supposition, from a strictly Benjamin Sense, needs to be seen not merely as a representation of a classical art form or its subjects being compartmentalized into a modern space for cultural criticism, rather such spaces need to be also seen as something that helps in the re-emergence of a time, documented as it is, through the embodied interaction of everyday spaces and everyday time, all in terms with the changing politics and culture of the present. In other words, the task of any spatial turn is to carve out a performative arena that transcends the everyday lived realities. Mundoli Narayanan transcends such a performative space by seeing history in the here and now, as it is, without any scope for dilutions or reductionisms.

Space, Time and Ways of Seeing: The Performance Culture of Kutiyattam is a critical text which talks not just about a particular period through taking a classical art form for cultural criticism. Rather it comes as a larger attempt to motivate its readers to identify multiple entry points through seeing Kutiyattam as a political play, as much as it is a cultural manifestation of the here and now. In other words, the book mind bombs intricately with a deep sense of the past through documenting the present aesthetically, primarily because, politics forever governed the majority of the spaces, and ways of seeing can be no less political in the case of Kutiyattam too.

Kutiyattam, its space and the political present

Kutiyattam is one of the oldest performance traditions in the world and certainly the oldest existing performance form in India. It is the only living form of Sanskrit theatre and has a history of more than ten centuries. In recognition of its antiquity and theatrical richness, UNESCO declared it a “Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity” in 2001. Traditionally the art form was performed only in kūttampalams, the temple theatres of Kerala. It is a theatrical form that employs a consummately conventional style of performance, composed of a blend of emblematic costumes and make-up, symbolic gestures, stylised movements and facial expressions, and a unique method of dialogue rendition that is said to resemble Vedic chants. The stage is usually bare, except for the performers and the musicians. There is no scenery, very few props and the only source of light is a single bell-metal lamp with three wicks burning (Narayanan, 2006a, 122).

With a distinctive set of performance systems and a permanent repertoire that comprises some of the core texts of the pan-Indian tradition of Sanskrit drama, written by Bhasa, Harsha, Kulasekhara, Saktibhadra and Mahendra Vikrama the art form emerged as an art form mainly in the state of Kerala, which is in the southern part of country India. However, an interesting fact about Kutiyattam that emerged as a radical play in Kerala is that, apart from barring three plays, Āścaryacūdāmaṇi (The Wondrous Crest Jewel) by Saktibhadra and Subhadrādhanañjayam (The Wedding of Arjuna and Subhadra) and Tapatīsaṃvaraṇam (The Sun God’s Daughter and King Saṃvaraṇa) by King Kulasekhara Varman, which are of Kerala origin, the rest of the plays presented on the Kutiyattam stage are primarily those of Bhasa, Harsha, Saktibhadra and Mahendra Vikrama, all of whom are from other parts of India and have enjoyed pan-Indian popularity. Embedding the art form with nationalist fervours or conservative imaginations therefore cannot be subjected to in the case of Kutiyattam. The same has been unveiled quite eloquently by the author. Narayanan says:

Indian-ness” has of late become a convenient handle for a rather thinly veiled and aggressive nationalism that takes strenuous, and sometimes even violent, exception to anything that is considered external or foreign……. the practice of theatre and performance, despite its local characteristics and culture-specific structures of evolution, is still not limited to any one place or time and has a universal character and shared features that cut across cultures and climates (Narayanan, 2022).

The perseverance of the author to see the space and time of Kutiyattam, especially in a far-right-dominated and sanskritized society would have proved to be a compelling task. But without any doubt, he has surpassed all such problematic phases through a well-manufactured ease, by employing an ‘essential nihilism’ (not in terms of the literariness of the text, but in terms of the attitude towards the world), which would have helped him in explicating the contours of seeing and speaking things, of only what one has seen and spoken. In other words, experiences and lived realities enrich the rigour of this text, as documentation by the author is mostly out of his empirical observations and unparalleled theatrical as well as theoretical expertise. This in a way also confirms that the text is not subject to any imaginary falsifications.

The book is divided into six chapters which majorly look into space and time through different performance lenses such as doing, seeing, digressions, dissonances, body, socio-cultural and so on. Chapters are preceded with an Introduction on the spatial turn that begins through a critique of the historical silence of Aristotle, who had little to say about the space of performances in his Poetics. Further, the performative space is explored by taking the Natyasasthra of Bharathamuni and also by taking certain theoretical premises on space spoken by multiple theorists such as Maurice Merleau Ponty, Michel Foucault, Henri Lefebvre, Edward Soja and others.

Spatial turn

In Abhinavabharati which isa commentary on Natyasasthra Abhinavagupta observes that, if the playhouse is too small, problems such as seeing and hearing will be affected, irrespective of even if the actors and spectators are too close to each other (see Bharata-Muni, 1987. Vol. 1, 110, 1956, 53). Perhaps it is also at this point of intersection, that the very emergence of a traditional pan-Indian art form of Kutiyattam needs to be seen and expanded in contemporary times. Kutiyattam today is a widely accepted public performance, which needs to remain accessible to all for critique, irrespective of knowing or not knowing Sanskrit. Such an epistemic arrival also helps in loosening the clutches of the hegemonical orders, as the art form becomes accessible to the public who otherwise lacks access to kūttampalams because of their lineages and castes. The author however finds that the radical shift in the performance space from the kūttampalams to secular stages in public venues and the corresponding alterations in the various spatial configurations of the form have impacted the triangular relationship among the space, the actor and the spectator which earlier had remained more or less unchanged for nearly five centuries.

Such changes are looked into by the author in terms of the spatial turn in theatre and performance studies, as well as through the problems resident in the taxonomies and approaches already developed. The author posits the consciousness of space as a constitutive category that could not be merely reduced or collapsed to any other. The ideological premise of the spatial turn therefore becomes broadly more social and geographical in its dialectics. A major emphasis that the author gives throughout this book is on the concept of the here and now which is precisely an understanding of the ‘lived spaces’ and the ‘given spaces’ that equal to ‘social spaces’. This is carried out by the author by looking into the performance that unites the actor and the spectator. The theatrical practice of Kutiyattam is seen through the form of a triad where live actors and live spectators come together in a live space, distinct from other quotidian activities based upon interdependent actions and perceptions. Motivating the functioning of the triad in theoretical terms author adopts a phenomenological approach.

Phenomenology is the theoretical framework employed in this work and it is explained very lucidly. A phenomenological approach is mainly adopted to explain the relationship between performers and spectators in Kutiyattam and to situate the same in terms of the space in which it comes to be. Maaike Bleeker et al. state, “Both performance and phenomenology engage with experience, perception, and with making sense of processes that are embodied, situated, and relational” (2015, 1). After a critical look into the performance of Kutiyattam author posits that, it is not what things are but what they appear to be, what they seem to be, that is important in theatre, and this “the world as given in experience” quality of theatre and performance makes them natural candidates for phenomenological analysis. Alongside this also stands the fact that our foundational experience is always already socialised because it takes place in a world shared with and formed by others (Bleeker et al. 2015, 8).

Adopting a phenomenological framework for the study is primarily motivated by the works of the doyen in phenomenology Edmund Husserl. This in a way also has helped the author to dig deep into the intricacies of the art form by standing equally inside as well as outside of the art form (here Kutiyattam).

A slight digression to the political present in a way also marks a spatial turn for Kutiyattam because all art forms carry in them a deep-seated politics that cannot miss the way of seeing any art. A supposition of this kind is made primarily because today we live in a world of newly manufactured histories that valorize classical art forms to a horrifying and improbable limit. Kutiyattam is an age-old art form that uses Sanskrit as a medium for instruction and cannot be ever pushed into as a tool for making political claims through breeders.

This text therefore needs to be seen along similar lines wherein no scope is created for any kind of an ultra-conservative backlash or twisting of facts as the book is written as it is without digressing from the classical art form that becomes the stage which is Kutiyattam. Hence no art can ever go apolitical and all apolitical manifestations translate to be equally political in some or the other.

Such expertise in considering the political ramifications that Kutiyattam may become subjected to at a certain course of history would’ve stemmed mainly because of the author’s deep association with the works and life of a yet-to-be-fully known to the world, an erudite classical Marxist, late T K Ramachandran. This review also starts with his proposition of the ultra-conservative backlash.

With access to the best of the people who have mastered not just the field of Kutiyattam but also the field of political and cultural criticism, this book employs a triangular relationship through employing two modes which are the performer (ways of doing) and spectator modes (ways of seeing). Such an eye for detail enhances the space around which this text revolves. From now on Kutiyattam can be seen with a greater eye for detail by the spectators with the emergence of this seminal text that would forever survive the test of time. Kutiyattam is an art for all, and no boundaries can fixate it. It is perhaps high time for a society to radically transcend such an art form by making it more public rather than holding on to its classical texture. That happens only when the historical materialist brushes history against the grain. Mundoli Narayanan has just done that. Having done that also means he foresaw the ultra-conservative backlash!

References:

- Benjamin, Walter. 1992. Illuminations. Edited by Hannah Arendt and translated by Harry Zohn. London: Fontana Press.

- Bharata-Muni. 1956. Nāṭyaśāstra of Bharatamuni: With Commentary Abhinavabhārati by Abhinavaguptācārya. Edited by M. Ramakrishna Kavi. Vol. I. Baroda: Oriental Institute.

- Bleeker, Maaike. 2008. Visuality in the Theatre. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Narayanan, Mundoli. 2006a. “Kutiyattam: Traditional Structures of Patronage and Setting.” In Patronage, Spectacle and the Stage edited by Irene Eynat-Confino and Eva Sormova. Pp. 28-41. Prague: Theatre Institute.

- Narayanan, Mundoli. 2006b. “Over-Ritualization of Performance: Western Discourses on Kutiyattam.” TDR: The Drama Review.50 (2, T190): 136-153.

***

Sankar Varma is a research scholar in the Department of Economics, Christ (Deemed to be University).