The past few years have been transformative for Uttarakhand’s music scene. On one end the catchy tune “Gulabi Sharara,” (2023) became a viral sensation, surpassing more than 300 million YouTube views to date. You couldn’t scroll through social media without coming across someone trying those dance moves. And on the other, Kamala Devi, a folk singer rooted in hills, quietly made her debut on Coke Studio Bharat with “Sonchadi,” (2024) bringing the raw beauty of mountain folk to a national stage. But long before the era of algorithms and instant hits, some voices didn’t just rise and fade rather they stayed with us, echoing for generations. From crackling radios of the 1970s to concert stages of the early 2000s. My nieces can perfectly mimic those “Gulabi Sharara” moves but it is my grandmother who still hums her songs. Most folks outside her village never knew her name, but everyone knew her voice and lyrics. Women of her village affectionately called her “Kumain,” a local term for natives of Champawat district, formerly known as Kali Kumaon. Her melodies echoed through forest trails, across border posts, and comforted migrants far from home.

What the Dam Will Erase, The Valley Remembers

On March 26, 2018, during our first year as undergraduates, my friends and I set out on a five-day, over 120-kilometer foot journey to survey the socio-economic, cultural, and environmental implications of the proposed Pancheshwar Dam along the Indo-Nepal border. Guided by renowned environmentalist Dr. Shekhar Pathak and Professor Prakash Upadhyay. We began our journey at Jauljibi in Uttarakhand’s Pithoragarh district, where the Kaliganga and Goriganga rivers meet in a flowing confluence. Our journey ended at Pancheshwar in Champawat district, where the Kali and Saryu rivers unite to form the Mahakali River, known as Sharda, a site now designated for the construction of what could become one of the planet’s tallest dams.

Confluence of Gori ganga (left) and Kali ganga (right) at Jauljibi | Women returning at dusk with firewood from the Kali Ganga’s banks |

The Kali Ganga forms the natural boundary between India (left) and Nepal (right) at Jhulaghat | Walking the sun-baked riverbed of a Kali Ganga feeder stream |

As the third day of our “yatra,” as we call it, began, Prof. Pathak dropped a bombshell: “We are going to meet Kabutari Devi on the way.” Our teenage brains, freshly out from one of the school froze. We exchanged puzzled glances, equally clueless, and asked, “Kabutari Devi?” It was the first time her name had reached our young and dramatic lives. Noticing our confused faces and the sudden, yet significant, awkwardness we three had created, he took up the baton and recited her most cherished lyrics, lines once aired on Akashvani:

“आज पनि जौं जौं, भोल पनि जौं जौं,

पोरखिन तै न्हैं जोंला।

स्टेशन सम्म पुजाई दे मनलाई, पछिल विरान होये जौंला”

Kumaoni to English: “I must leave today, perhaps tomorrow — but by the next, I’ll be gone for sure. Just see me off at the station, for beyond that, I’ll be no more than a stranger.” Though we had grown up hearing these lyrics, Kabutari Devi’s name remained unknown to us until Prof. Pathak’s revelation, ultimately proving Alexander Pope’s (1711) observation correct three hundred years later: that partial knowledge can mislead.

Dhiraj (far left), Prof. Pathak (second from left) and Prof. Upadhyay (Far right) in conversation with a resident during the interview

When the Himalayas Found a Voice

Born in 1945 into a Dalit household belonging to Mirasi/Gandharva sub-caste (a community historically associated with music) in Champawat district. Kabutari Devi was the third among her ten siblings. Her mother, Devki Devi, sang Thumri and Bhairavi, while her father, Dev Ram, was a multi-instrument player and a Ghazal singer. Kabutari Devi took her musical education from her mother and learned Phaag (wedding songs), Chaitol (songs on spring season) and Nyoli (serene forest tunes) along with classical music. Her maternal grandfather was a Ustaad. As a child, she frequently accompanied her mother to upper-caste households to learn and perform.

Encouraged by her husband, Diwani Ram, whom she called “Netaji,” Kabutari joined Akashvani in 1979 after passing the vocal tests, her songs aired from Lucknow and Najibabad stations (Joshi, 2018). For her, folk songs carved space for a voice often erased by caste and gender hierarchies. In a documentary interview, Sanjay Matto and Uma Bhatt asked why her siblings hadn’t matched her success, she replied “Unke paas Netaji nahin the naa isiliye” (“They didn’t have a Netaji like I did”).

A Lifetime Achievement in Survival

People used to call her “Pahado ki Begum Akhtar.” She drew inspiration from Lata Mangeshkar, claiming, “Mujhe koi bhi gaana dedo Lata Mangeshkar ka, raat bhar sunungi aur subah mujhse waise ka waisa hi sunlo” (“Give me any Lata song; by dawn, I’ll sing it back to you note for note.”) She carved a unique place for herself in a space dominated not just by men, but also by caste, where subaltern voices are often silenced. Her music became a form of cultural resistance, challenging dominant hegemonies[i] and offering a counter-narrative grounded in Dalit identity (Guru, 2009). After her husband died in 1984, Kabutari Devi’s career came to a halt, and she went into obscurity. For nearly twenty years, Kabutari Devi lived a life of quiet struggle, working tirelessly as an agricultural labourer in other people’s fields just to make ends meet. The melodies she carried seemed to have been buried beneath the weight of daily survival. In a heartfelt conversation in 2018 with journalist Sudhir Kumar, she recalled how a turning point came when cultural artist Hemraj Bisht reached out to her in the early 2000s. It was he who helped bring her voice back into the public sphere. Over the years, she received several awards, including the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Uttarakhand government in 2016. Although these recognitions held great meaning, they did little to change her economic condition.

A glimpse of Kwitarh village in the Mahakali valley | Moving down Kwitarh’s well planned and colorful lanes |

A Begumpura for Others

Upon reaching Kwitarh village in Pithoragarh along the Mahakali valley, where she lived until her death, we were struck by the unexpectedly well-developed infrastructure and organization of the village, so much so that it felt as if Metcalfe had coined the term “little republics[i]” with this place in mind. As someone raised in Uttarakhand’s often-overromanticized Kumaon Himalayas, where villages typically lack paved paths, rely on mountain springs for water, and where ‘ghost villages[ii]’ bear silent witness to the exodus, Kwitarh’s colourfully painted paths, streetlights and water fountain left me feeling alienated[iii] in my homeland.

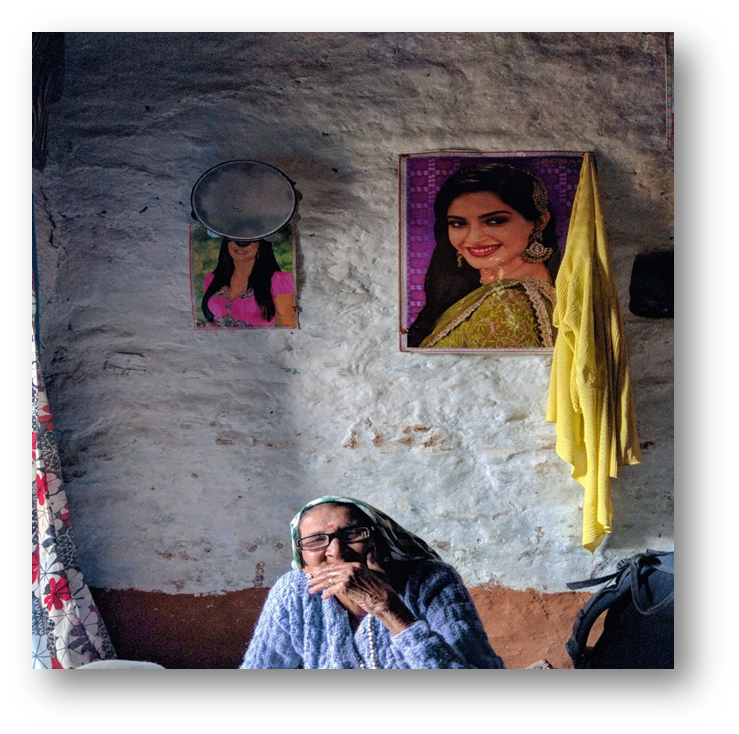

We were taken aback when we reached her home. It was a tiny structure with just two small rooms and a little kitchen. The paint was peeling off the wall and everything looked old and fragile. Despite the village’s ‘aesthetic’ progress, her caste status confined her to deprivation (Ambedkar, 1936). She spent her days with her granddaughter, Rinki, who looked after her and met all her needs. Her daughter, Hemanti Devi, keeps the family’s musical legacy alive as a folk singer, passionately upholding her mother’s artistic traditions. Kabutari also played a guiding role in the life of her grand-nephew, Pawandeep Rajan, now a celebrated singer who rose to fame after winning The Voice (2015) and Indian Idol Season 12 (2021). Through his success, her cultural and musical influence continues to resonate with new generations.

Kabutari Devi engaged in a conversation | A mirrored glimpse of Indira Gandhi’s portrait |

When we entered her spatially constructed room, we noticed posters of Indian celebrities along with posters of Hindu deities. One poster, nearly hidden behind her Dafli (a drum central to her performances), featured actress Katrina Kaif, showing how mainstream popular culture overshadows folk traditions even in their own spaces. However, the photograph that truly caught our attention was a portrait of Indira Gandhi, whom she deeply admired. When Prof. Pathak inquired about her health, she admitted in a panting voice“Ab kuch yaad nahin rehta, sab bhool jaati hu” (“I hardly remember anything now, I forget everything”). She even struggled to recall songs she had sung countless times.

Kabutari Devi and Prof. Pathak: A moment of shared admiration (Photo by Dhiraj)

The Station she Never Left

As her trembling voice filled the room, it carried the quiet weight of goodbye. Four months later, in July 2018, she passed away, as if the lines that Prof. Pathak recited in the beginning had foretold her departure. Her voice still echoes through the Mahakali valley, remaining with us not merely as a memory but as a feeling. Two months after her passing, we had the privilege of attending the premiere screening of Apni Dhun Mein Kabutari (2018), Sanjay Matto’s documentary that beautifully captured her bold, unshakable spirit.

The poster of the documentary Apni Dhun mein Kabutari at Nainital |

[i] Metcalfe described Indian villages as peaceful little republics, but this was a colonial story that disguised control by calling tradition unchanging.

[ii] Ghost villages are what remain when people leave their homes in the hills, pushed by poverty, climate, or lost opportunities.

[iii] Marx saw alienation as the deep disconnection people feel from their work, from each other, and from themselves in a world ruled by capitalism.

References

Ambedkar, B. R. (1936). Annihilation of Caste. Self-published.

Guru, G. (2009). Rejection of Rejection: Dalit Assertion. In G. Guru (ed.) Humiliation: Claims and Context (pp. 45–67). Oxford University Press.

Joshi, S. (2018). Lok Ki Gayika: Gayika Ka Lok – Kabutari Devi [The Folk Singer: The Singer of the People – Kabutari Devi]. International Journal of Educational Research.3: 24–26.

Pope, A. (1711). An Essay on Criticism.

[i] Gramsci explained hegemony as the way the ruling class wins consent by shaping culture and ideas, making their dominance feel natural and acceptable.

***

Ajay Singh Karki holds a master’s degree in Sociology from Kumaun University, Nainital, with keen interests in photography, butterflying.

Kabootari Devi stands as a testamony to what women can achieve when they are supported at the right time by right people . Her passing away has been a huge loss to our state. She has been an inspiration for all the women as well as the folk artists. Hopefully the younger generation takes a leaf out of her book and uses the technology and reach of internet in the right way to carry forward the legacy of our folk artists and above all the culture of Devbhoomi Uttarakhand.